Okay…so…we get notes. We get feedback. We hear the gossip, the suggestions of angry whispering from one corner or another. First of all– there’s more, there always is; and I’m happy to acknowledge and eager to share it all—or at least as much as I can get down coherently on paper or a screen. Or a stone tablet. (That would be an edible.) But here’s the other thing. I’m just so fucking exhausted all the time. Obviously it could be worse. I could be some polar bear mama swimming 100 miles of icy (but not icy enough!) sea to get some food for her cubs and praying they’re alive if and when she ever gets back. But it’s been challenging. Politically. Physically. (Insert sound of person heaving violently here.) Like that. Daily. Most mornings before 11 a.m., I sound like the character Jennifer Coolidge plays in Mike White’s HBO series, The White Lotus—not the one who might be an ‘Italian opera heroine’ (an opera of the absurd, obviously), but the one who knows she’s “doomed.” So if at any point in the following I sound like that character, you’ll know I was scribbling it at some point before 11 in the morning and before the 10 essential espresso shots I need to see much less think straight have been mainlined into me.

It should be obvious that these are not just ‘honorable mentions’ or ‘Miss Congeniality’ runners-up to—(drumroll, trumpet fanfare)—’The Crown’. There’s a lot of noise in this town and there’s always going to be that sound and fury around a host of cultural (and political and planetary) issues throwing certain works into a kind of relief that in the moment leaves perfectly stunning work in the shadows. Except I wouldn’t even call it that. We see you. Maybe just not fast enough. In fact never fast enough. Sometimes you sort of have to fly in our faces a bit. I mean that literally. This morning I looked up from my desk to see a bird (not small either) perched on one corner of my piano. She suddenly began to chirp a kind of complaint. Something like ‘I’m starting to feel claustrophobic. As if you didn’t know. Please get me out of here! Now!—you stupid twit.’ I got up to open the front door—which would have made her exit route plain. Instead she immediately flew across the room to perch on this sculpture—shaped like … a tree branch. She had already figured out her Plan B. How did she size up the best options so quickly?

You have to let us (people like me—or for that matter my editors) triangulate a bit. We’re not exactly sitting still in the sky. We move around a bit (even when we mostly feel chained to our desks). It’s the same way in the City of Los Angeles. I think Nancy Holt (who’s included here) would have gotten this. Or maybe Shizu Saldamando. Just breathe.

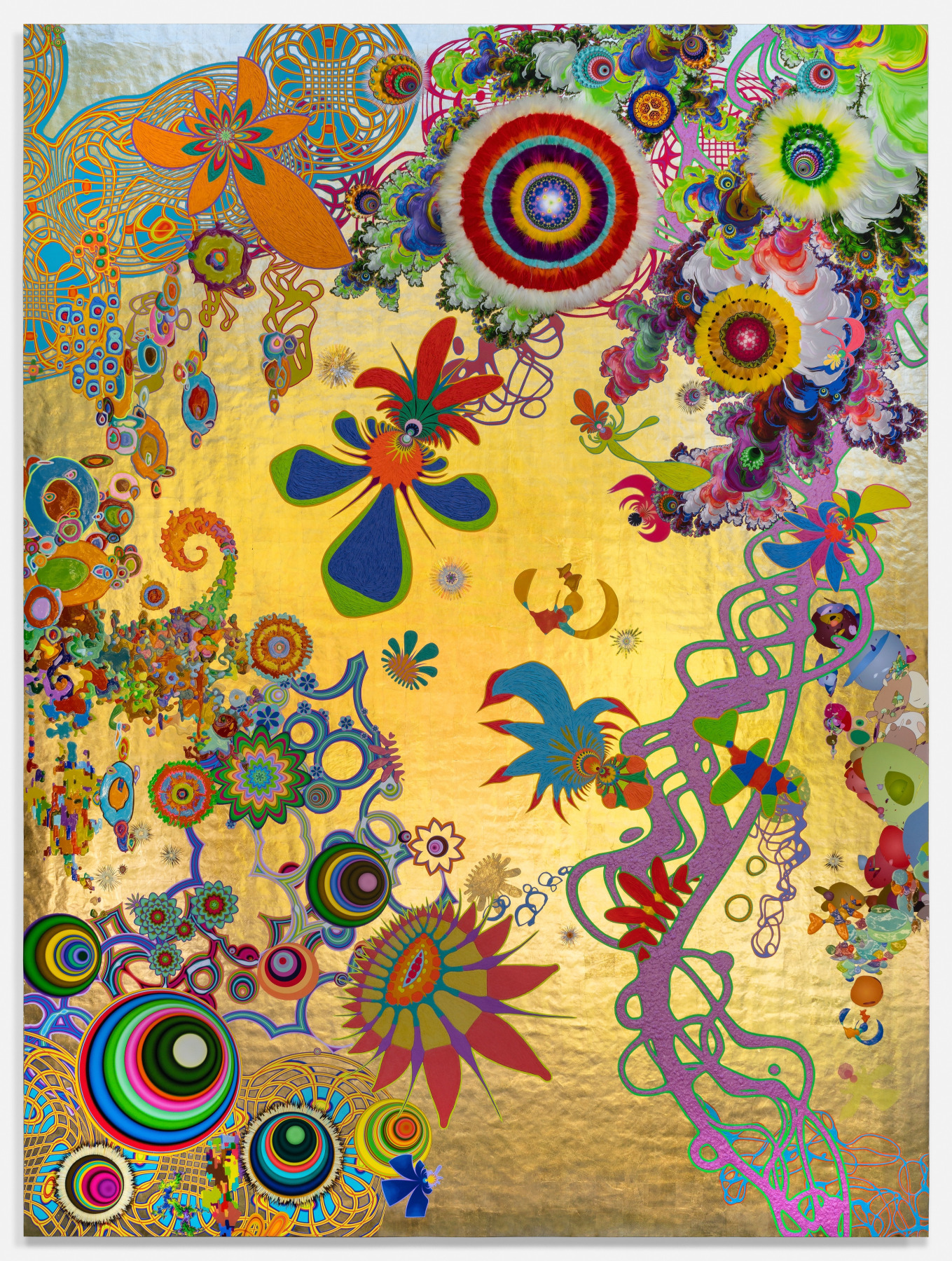

Patricia Iglesias Peco, Las Flores del bien, 2022. Courtesy of François Ghebaly.

Patricia Iglesias Peco — Naturaleza Viva

François Ghebaly

If you’ve looked at any of the second season of The White Lotus, maybe you’ve already taken in the scene where Jennifer Coolidge as Tanya gets taken to a performance of the Puccini opera, Madama Butterfly, at the Teatro Massimo, and is simply dazzled by the scene on and off the stage, culminating in Cio-Cio San’s aria, “Un bel di.” Well that was me with this show. Verklempt.

I felt driven almost to a state of intoxication by these paintings, which seemed to sweep me up as if on a wind-borne perfume distilled from these brushstrokes fashioned into foliage and flower petals, that might have been choreographed by the later, Mannerist Veronese in a Monet, Cezanne or early Bonnard palette. The brushstroke makes its very palpable mark on the canvas (or linen) yet is somehow also weightless. But more than that, each painting was a world unto itself: recognizably a larger or smaller fragment—but nevertheless an entire world.

As if that weren’t enough, in the next gallery Paulo Nimer Pjota debuted with what looked like an archaeological expedition in mixed media (Every Empire Breaks Like a Vase). It was like that dream or dream fragment you keep going back to and noticing something different. (‘Wait – did I leave that there? And isn’t that my Uncle Irving’s head – or, I mean, maybe something out of his office?’) It’s also a performance. Pjota is from São Paulo so I’m guessing he knows how to samba. It’s a ritual sacrifice. ‘Put out that cigarette—on that head over there. It will be your last.’ I could use one of those ashtrays on my coffee table.

Earlier that year, Sayre Gomez also showed a smashing new body of work. Remember Hollywood? Well it’s all on sale now. 99 cents or less. Or more — who’s counting? It’s all in bitcoin, or something crypto. Hey—they don’t call it crypto for nothing. Anyway it’s now called Halloween City and Gomez (as usual) nails it.

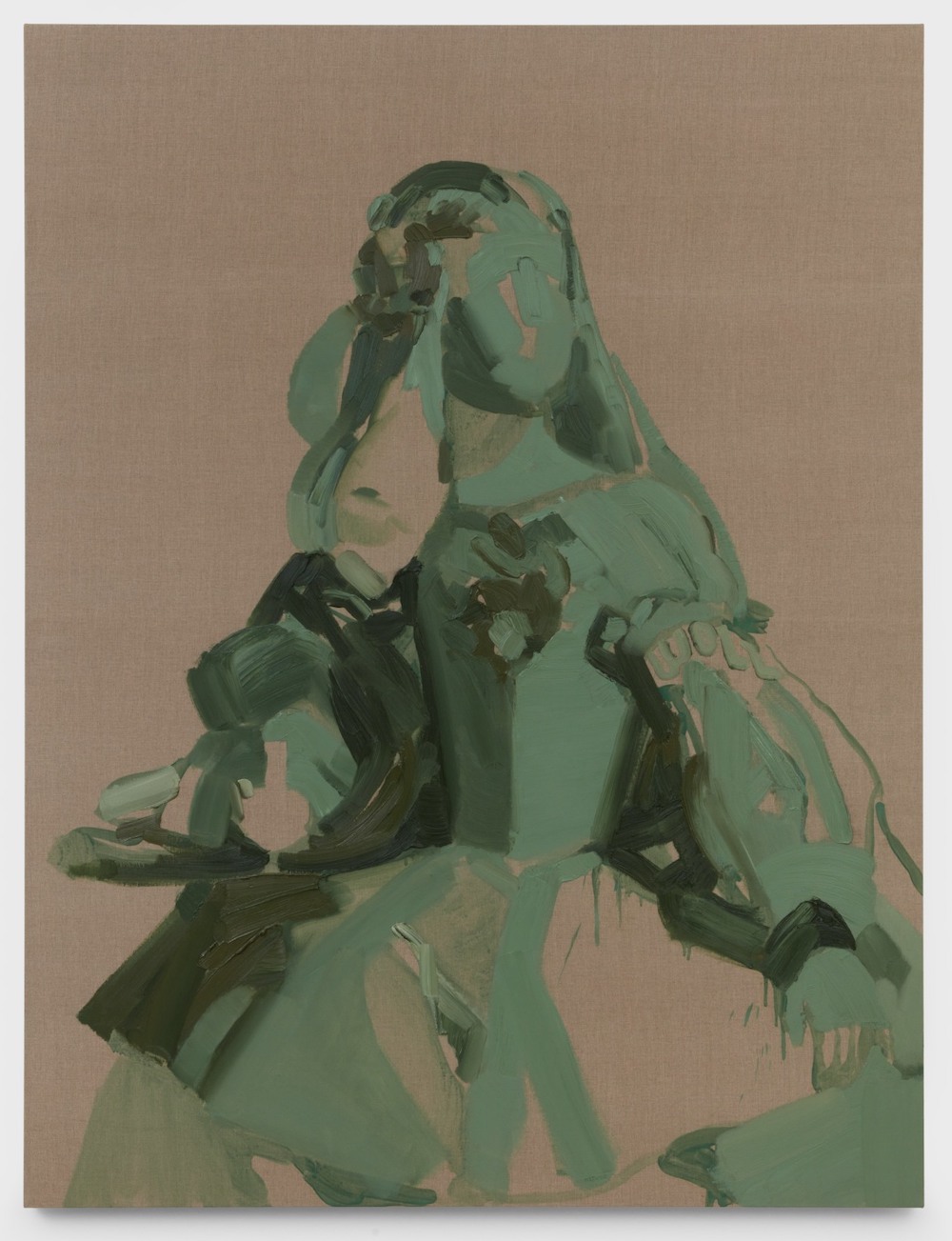

Andy Woll, Mt. Wilson (Princess Margaret Theresa, XII), 2022.

Andy Woll — Green Earth

Night Gallery

Across the alley, at Night Gallery, Andy Woll went to the mountains and discovered why we climb them and what they tell us. More specifically, he went to Mount Wilson where he took pick-axe and pitons—I mean brushes—to it and made a few discoveries. More specifically, that this is not the whole story; this has been going on a long time; this is not where it ends. Which is why this is also where we jump off to the stars. On the other hand, you could be Velasquez and make the same discoveries in the playrooms of Philip IV’s Buen Retiro palace. They didn’t call him the Planet King (seriously) for nothing. And there were horses. The End.

Katie Grinnan, Synapse, 2022. Courtesy of Commonwealth and Council.

Katie Grinnan — Synapse

Commonwealth and Council

Or sometimes you want to go deeper. Behind your eyes—or a pal’s (or a frenemy’s or an enemy’s). Maybe find another creature that expresses it better (or at least companionably—a girl’s dream). Shankar Vedantam calls it ‘hidden brain’—but actually there’s a kind of gut-level extension to our cranial-heavy perceptual and reasoning capacities we call the enteric nervous system. And how is it we’re putting all this together? And how do we actually make these leaps—to actually extend, expand, intersect, interweave consciousness? To expand our truly limited, almost shackled intelligence? Katie Grinnan had some thoughts and really went out on a limb (or maybe an octopus arm) to deliver.

Ross Bleckner, After 51 Years (111), 2021. Courtesy of Vielmetter Los Angeles.

Ross Bleckner — Sehnsucht

Vielmetter Los Angeles

It’s been a while since I connected with Ross Bleckner (how about you?), and this show took me down a dark, subterranean, even slightly brutal, road—but seemingly beneath the sea. (Is that where we’re headed? It certainly feels that way sometimes.) In a way this show was an inversion of the Patricia Iglesias Peco vision and sensibility (though not exactly at the same level). I walked through it as if I were seeing it in the after-life. Maybe I’m not really here after all.

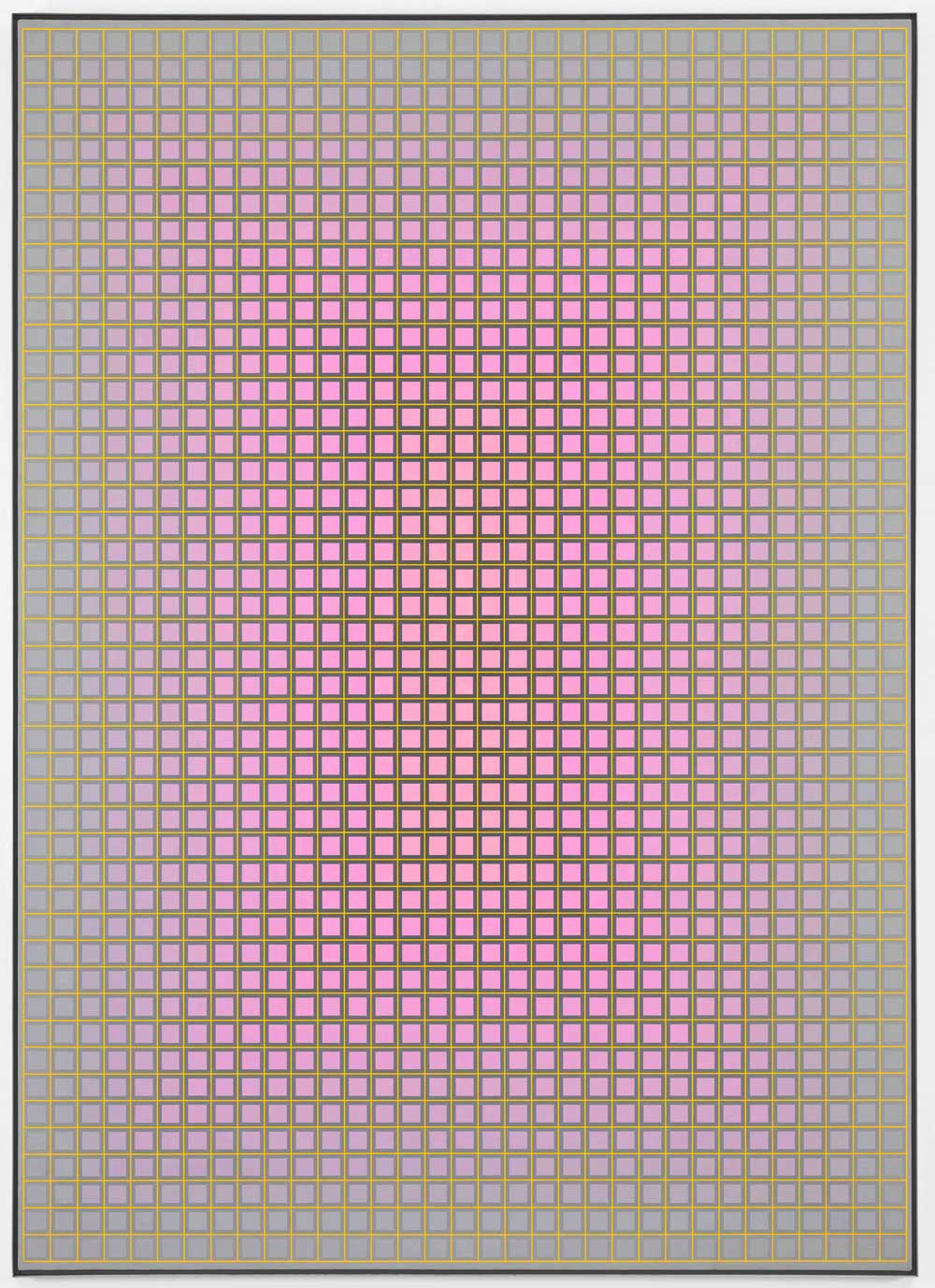

Julian Stanczak, Glow, 1973. Courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery.

Julia Stanczak — The Light Inside

Diane Rosenstein Gallery

And then there was Julian Stanczak. We’re always looking closely—sinking our eyes into an artist’s work, some (hopefully all) of which pulls us deeper, further, in any number of directions. And not so surprising that some of these directions put us into some fairly obscure corners, folds and pockets—some of them quite dark in every sense. (It’s not ‘fin de siècle’—it’s fin de civilization—and conceivably well beyond). In this compact but truly dazzling survey, the late master does a number of extraordinary things—including effectively giving us that ‘sink’ back—moving our eyes across innumerable fields and directions, and (as I put it in a posted essay), fresh horizons.

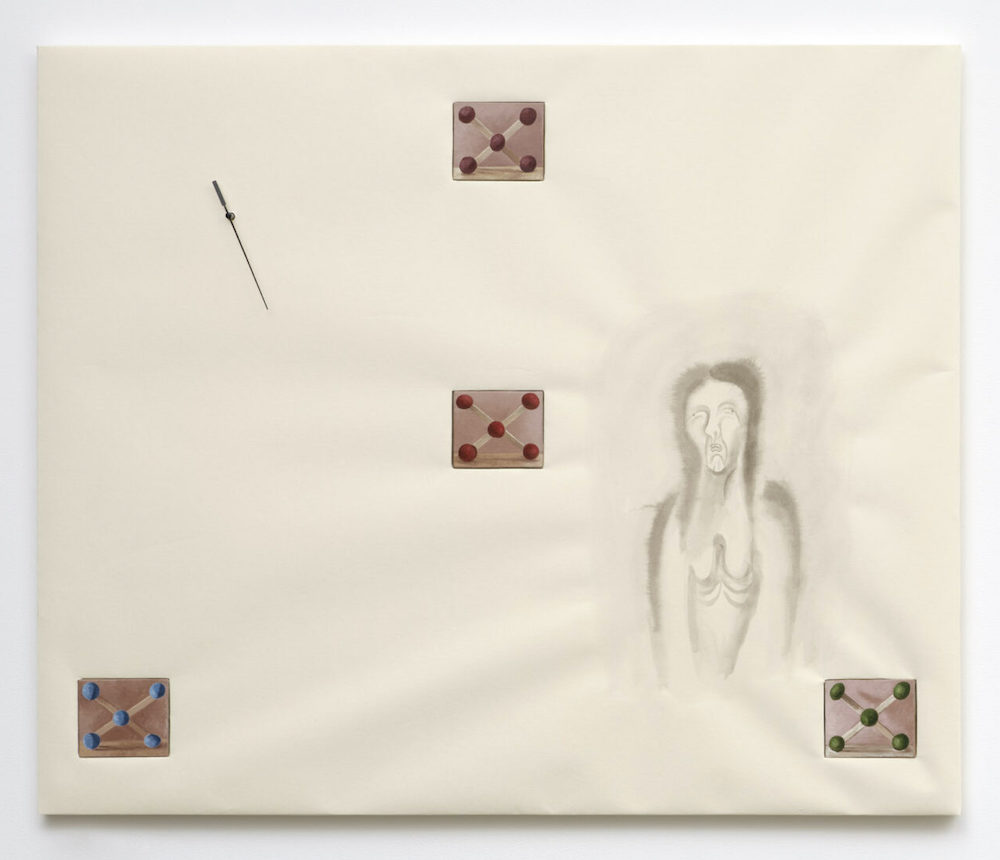

Masaya Chiba, Like multiple objects intersecting as they grow / drawings with ghosts, QR code, sound, time (#4), 2022.

Masaya Chiba — Appearing → Talking about the object of regrets or obsession → Dancing → Leaving (resting in peace or just simply leaving)

Bel Ami

Sometimes the most fascinating work flies at us (or just as often—seeps into us) from a place or conceptual frame we have no way of coherently apprehending or describing, much less physically situating ourselves within. It doesn’t have to be ‘exotic’ in any conventional (or unconventional) sense to effect this kind of distance or shift of mood and perspective. Chiba’s show had that kind of osmotic and multivalent effect, notwithstanding the distinctive and disparate elements that composed the work and show as a whole—everything from Noh theatre to traditional Japanese arts, painting and mythology, to chemistry and molecular biology, to everyday objects—recomposing not merely a way of seeing or narrating, but of experience itself, of being.

Jose Alvarez, I Wish You Were Here, 2020.

Terms of Belonging (group show curated by Efrain Lopez)

Gavlak Gallery

This was a fascinating, brilliantly curated group show of mostly Latin American artists (including U.S. born or based Latinx artists) that, on one level seemed to pick up where the Hammer’s brilliant 2021 No Humans Involved exhibition left off in terms of unpacking legacies of colonialism, but went far beyond it on a number of other levels, to interrogate the sheer sense of place itself, and our relationships with it (irrespective of its function as an aspect or signifier of identity).

Installation photograph, Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, April 24–October 9, 2022, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse

LACMA — Resnick Pavilion

One of my great regrets of 2022 was not posting any of my notes on this gorgeously and rigorously curated show of McQueen couture (including some ready-to-wear and custom pieces), deftly integrating and informed by examples of the kind of art that directly or indirectly shaped, conditioned or inspired his themes, design concepts and technique and the larger vision that subsumed it all. The exhibition showcased Regina J. Drucker’s magnificent collection of McQueen designed fashion, which she has gifted to the Museum (not so incidentally making LACMA the largest repository of McQueen’s work in the United States). No less noteworthy (further emphasized by the excellent catalog I only saw some months after the show had opened) was that the exhibition became a showcase for the scope and depth of LACMA’s own permanent collections and its outstanding curatorial resources—led here by Clarissa M. Esguerra and Michaela Hansen, the Costume and Textile curatorial team, and curators throughout LACMA’s departments.

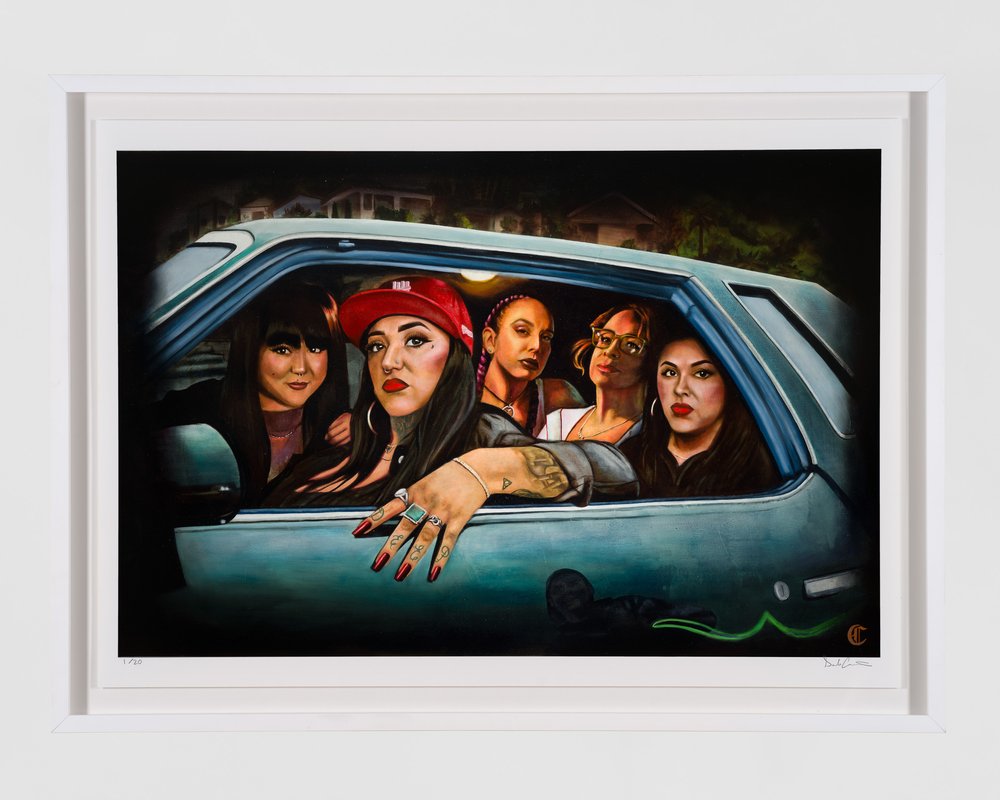

Danie Cansino, Cruise Now, Cry Later, 2022. Courtesy of Charlie James Gallery.

Danie Cansino – I’m Starting to Forget

Charlie James Gallery

Danie Cansino’s U.S.C. MFA thesis show was already the buzz of the L.A. art world less than a year earlier, but her trajectory to both MFA and gallery debut was far from conventional. Before pursuing art formally, Cansino was a professional tattoo artist. You’d have to be legally blind, though, not to see that Cansino would need a much bigger ‘canvas’ to pursue the scope of work she was clearly born to do. Whether it was Cansino herself or some other not-legally-blind person who planted the idea, the rest is herstory. Cansino characterizes her figurative style as a kind of tenebrist realism—but it’s much richer and broader than that. This is an artist and image-maker of astonishing pictorial and narrative power and scope, at the beginning of what promises to be a very important career in both art and the culture at large.

But of course that wasn’t enough. In what seemed to be the fashion of the year, Charlie James delivered still more shows that—excuse my devolution to show-biz terms (but hey that’s half my DNA)—killed—most notably Rostro (curated by Ever Velasquez) that, pace Ghebaly, Gavlak, etc., could have been in a museum. (Okay—I exaggerate, but not by much.) I’m not going to bother listing any of the artists here (including many recognizable names), but there were 40 of them.

And one of them was Shizu Saldamando, who delivered her own beautiful show of ‘pandemic’ portraits, Respira. Something I have to remind myself to do now and again.

Nancy Holt, Electrical System, 1982. © Holt/Smithson Foundation, Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York.

Nancy Holt — Locating Perception

Sprüth Magers Los Angeles

Holt’s artistic objectives were both larger and more specific than her partner Robert Smithson’s (and in truth, her approach to earth- or site-specific works and accompanying devices or studies is probably more comparable to James Turrell’s). Her focus is less on place as a specific geo-location, but at least as much on the way we perceive and move through it and onto the next position, place or location. This beautiful show re-creates one of her most beautiful (literally radiant) installations, Electrical System (1982), in addition to bodies of work that poetically frame the peculiar ways the human species bookends its passage through this part of the United States.

Nancy Holt. Image from the series Western Graveyards, 1968.

And—as promised last year—Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group (curated by Michael Duncan) appeared at LACMA (in the Resnick Pavilion) before the Winter solstice, making spirits bright—no small feat situated only a matter of a few meters away from LACMA’s sprawling Afro-Atlantic Histories.

For those ready to venture beyond the city limits, The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, spotlighting work by such artists as Carlos Almaraz, Gronk, Frank Romero, John M. Valadez, Patssi Valdez, Einar and Jamex De La Torre, opened to acclaim.

In New York, Wolfgang Tillmans’ mid-career retrospective, To look without fear, gave us the most expansive view to date—of Tillmans’ fluid photography practice within a no less fluid and continuously morphing contemporary social space—the ‘lived-in’ world, as experienced immersively and in a moment-by-moment continuous present-tense. The show will be traveling to San Francisco, but not Los Angeles.

In collaboration with the Fraenkel Gallery of San Francisco, the David Zwirner Gallery mounted Cataclysm: The 1972 Diane Arbus Retrospective Revisited in its Chelsea space—a replication of her celebrated posthumous retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art that at the time provoked a divided (and heated) critical response. Yet today, the underlying rationale for much of the criticism leveled against the work (including that of well-regarded and still important critical voices) seems almost entirely untenable. Needless to say I have notes. But at this point I’m inclined to let the work speak for itself.