Considering the degree to which historians live in the past, Amelia Jones may not be what you’d expect. Confronting cultural biases relating to the politics of identity, she seems as much social activist as art historian.

Via art history, Jones speaks out against the art world’s entrenched sexism and racism, challenging the field’s most authoritative voices for insistently promoting a straight white-male perspective. She has made a bold commitment to write about historical and contemporary artists of color, female, gay and queer artists, describing the contexts from which their work has emerged and how and why their art is significant. She addresses the inaccuracies and omissions that have often erased their contributions to both past and present discourse. All of this couldn’t be more relevant to our time.

For years Jones has rooted herself in Southern California and its university art programs. She came to Los Angeles in the mid-1980s to earn her PhD at UCLA, taught at UC Riverside during the 1990s, and then went abroad to teach at universities in Manchester, England and Montreal, Canada. She is now Vice Dean of Critical Studies at USC’s Roski School of Art and Design, which involves overseeing undergraduate and graduate art history and theory coursework and helping to shape the curriculum.

I interviewed Jones early this year, before an eruption of public controversy over the school’s recent policy and curriculum changes. We spoke mainly about her academic writing, but in the process I came to realize how important teaching is to her and at the heart of writing and teaching, her love of art history.

As an undergraduate student at Harvard, there were a few fits and starts with her direction: literature, psychology, history. Like history courses at that time, art history could be dull: lots of rote memorization. “But it was fun to memorize because you were looking at things,” Jones says of her initial experience studying art history. She went on to earn an M.A. in art history at the University of Pennsylvania, then transferred to UCLA. By the time she arrived in Los Angeles, scholarship had advanced light years beyond rote thinking. Relatively new European theoretical frameworks were introduced into American academics, just as UCLA was developing an art history critical theory program. “It was 1987 and they had just hired Donald Preziosi; he was the first person in the field of art history to my knowledge who was teaching post-structuralism,” Jones says. “And I was minoring in film; a really cool combination. It was like this brief moment where academia felt important. People were debating philosophical issues.”

The topic of Jones’ dissertation certainly stirred debate. The essential point addressed American art criticism and Duchamp’s influence on the development of postmodernism, which she argues was being overemphasized to the exclusion of influential women in New York Dada, such as the outrageous Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. “I was looking at the construction of postmodernism on the back of Marcel Duchamp, so it was a critical analysis of [scholarly contemporary art publications] October and Artforum. They were saying: ‘postmodernism is about “the death of the author” and Duchamp is the artist who founded postmodernism.” And I was like, ‘But you just said it was about the death of the author, so why are you now finding another male artist to be the origin of postmodernism?’ I was tired of seeing all the histories of New York Dada pivot around Duchamp and Man Ray and Picabia and erase all this energy of people like the Baroness and feminist lesbian avant-gardes who were laying this groundwork.” She turned the dissertation into a book, Postmodernism and the Engendering of Marcel Duchamp (1994), which also led to another book, Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada (2004).

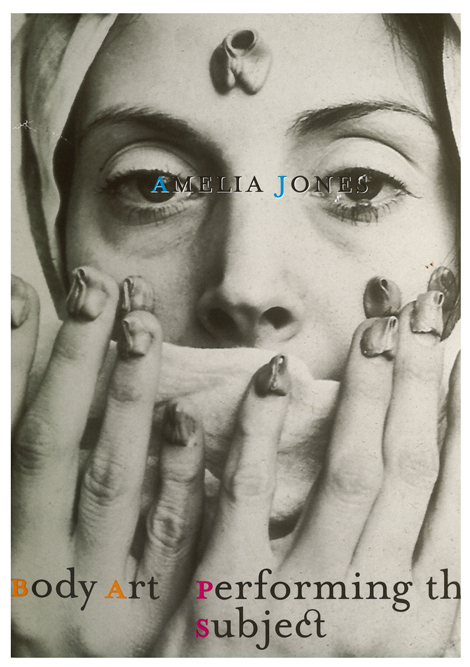

Book cover, Amelia Jones, Body Art: Performing the Subject, University of Minnesota Press, 1998 (with detail from Hannah Wilke’s Starification Object Series).

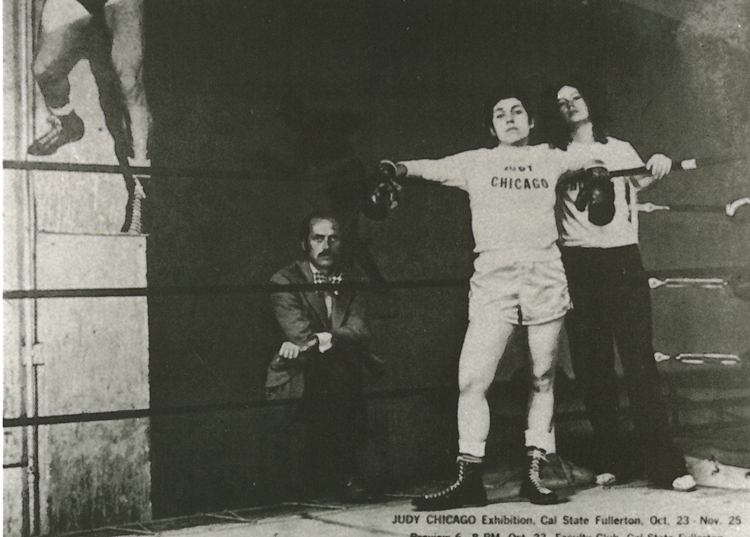

As that scholarship was being published, Jones taught and also worked on another research project that resulted in her excellent book, Body Art: Performing the Subject (1998). In Body Art she contextualizes the work of performance artists such as Marina Abramovic, Vito Acconci and Hannah Wilke within the framework of post-structuralism and applies feminist theory to examine dynamics at play between their quite diverse practices. Jones draws a relationship between “body art” and contemporary performance art. She says: “The book was initially sparked when I started teaching at Riverside and I would run across this really interesting stuff: In Artforum from the ’60s you would see these advertisements with artists obviously being ironic or funny: the famous Judy Chicago one in which she’s dressed like a boxer, and the Ed Ruscha one, “Say Goodbye to College Joys,” where he’s lying in bed with two women. And I remember thinking: ‘something’s going on here, and no one is taking about it.’” Jones attended live performances by SoCal artists, researched material from Electronic Arts Intermix and the Long Beach Video Archive, and had early access to Judy Chicago’s papers on her performances and activities.

Judy Chicago’s December 1970 Artforum advertisement, in Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in Feminist Art History, edited by Amelia Jones, University of California Press, 1996, p. 51.

Fast forward to now, and Jones has written, co-authored, and edited numerous books and articles on a range of topics. Most focus on performance art and theory—her area of expertise—although she also writes about artists who explore modes of self-identity through other disciplines. “Hysterical Bodies,” “Presence in Absentia,” “Duchamp’s Phallus,” “The Obscenity of Whiteness”—these are some of the engaging partial titles of her provocative journal articles. Beyond snappy titles though, academic writing can be daunting and slow going, and Jones’ prose is thicker than most. She weaves together perspectives from multiple disciplines: feminist and queer studies, film theory, Marxist theory, linguistics. This intertwining greatly complicates things, but it perhaps necessarily conveys the real complexity of issues at stake.

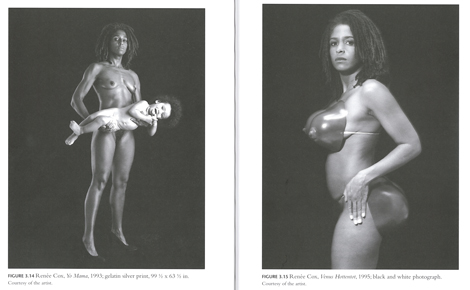

Renée Cox, Yo Mama, 1993, gelatin silver print; in Amelia Jones, Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts, Routledge, 2012, p. 94; Renée Cox, Venus Hottentot, 1995, black and white photograph; in Ibid., p. 95.

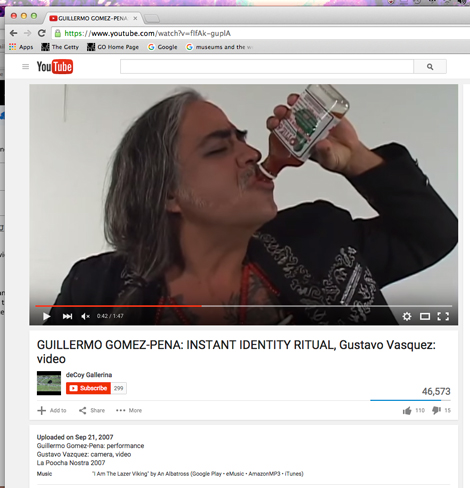

Jones’s most recent single-authored book, Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts (2012), addresses identity politics. Seeing Differently confronts racism within the present-day art world. In it she explains that since the early 1990s, political and popular press rhetoric has proclaimed the “death” of identity and that we are “beyond” such discussions. Jones (in this book and also many other writings) insists that we are not “post identity.” She profiles the work of some exemplary artists since the early ’90s who address the insidious nature of racism: Martha Wilson, Renée Cox, William Pope.L, Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Glenn Ligon, Susan Silton, Catherine Opie, to mention just a few. Seeing Differently implicitly raises the question: “What are we going to do about this?” And during our conversation, Jones makes clear that “racism” can be thought of as a broad term that speaks to many types of exclusionism, deeply rooted in legacies of conflict and pain. She says: “On some basic, inherent level, it’s actually not about skin color. It’s about the way that we hierarchize groups of people. And in [certain] cultures it gets attached to race or to ethnicity or to class.”

Reading her texts, one might wonder about Jones’ own identity. In some of her writing, to achieve a point she makes this clear: she is white and heterosexual. She also describes her upbringing, in which she attended all-black schools in North Carolina, and more recent experiences living in other countries, where her language or accent made her and family members stand out—examples that illustrate the point that lived experience also informs perspective. Jones describes how her childhood informed her writing. “Seeing Differently begins with me saying: ‘I grew up as a white kid in the American South, going to all-black schools.’ I included the front of my high school yearbook from North Carolina, [showing many black students in front of the building] with two white people standing there, to make the point. People need to know, if they’re interested in how I’m framing that set of problems.”

Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Instant Identity Ritual, screen capture from YouTube, performance for a video by Gustavo Vasquez, 2007.

The act of framing does make a difference. Early in her career, Jones was considered a feminist scholar. “Race and class were much more central to my life as a child than gender was. Why I didn’t address race more centrally in my work is something that I interrogated,” she says, “because that’s a sign of my privilege as a white person. But feminist art history was a nascent, available discourse that I could attach myself to and make sense of at the time. Now everything I do is conditioned by [race] because I don’t allow it to seem invisible. At least half of the artists that I write about are not white by default; it’s just a point I make.”

Jones’ teaching and research are conditioned by her dedication to the issues she cares about; and underscoring that, her commitment to the contemporary relevance of art history. Up until her relatively new position at USC, she taught in art history programs. Colleagues viewed her more as a theorist than a historian. At Roski the emphasis is different, she says, with most students aiming to become practicing artists. Perhaps because of that, there’s a sense of urgency in Jones’ voice. “I feel that history [is important], especially being in an art school. They deserve to know, these students. Like even the idea of art. Where did that come from? Because the more they can know about what artists and intellectuals have done and thought about in the past, whether it’s directly related to visual art or not, the more empowered they are to make choices.”