There was astonishing buzz around Philippe Quesne’s La Mélancolie des Dragons at REDCAT last Wednesday night; and as a sucker for avant-garde theatre, I simply had to be there, heat or no heat. I felt cooler just looking at the stage set, which resembled a forest clearing under the first snow of winter. As the audience took its seats, you could glimpse four of the actors already in place in a cramped four-seater later identified a VW Rabbit parked to one side of the clearing. When the lights finally went down, the situation became clear – at least to those of us who lived through the 1970s and have some memory of those drug-hazy days that would continue for some of us into the 1980s. Four retro-rocking dudes (think metal, hair bands, etc.) roll into a wood, stoned out of their minds, almost unaware that their car has died beneath them. They drink beers and pass around bags of chips while listening to vintage 1980s rock until the fog starts to lift. As they emerge from the car and we see them in their hair-band glory, we also see that what at first looks like a flat screen in the middle of the stage is actually a trailer hitched to the car. As they finally begin to take stock of their predicament (sobriety will do that to you), a woman in a purple down jacket seemingly stumbles onto this scene, though eventually greeted by the hair-and-metal guys like a lost relative or old friend.

With their angel’s arrival (she’s a mechanic, too … sort of…), tricks and hi-jinks ensue – plumes of smoke (from beneath the car hood), disappearing and reappearing bodies, bubble machines, lit-up screen/trailer (with big-hair wigs), and—oh yes—inflatables (the dragons?). The inflatables eventually multiply to fill the stage; and maybe that’s a good thing, because nothing else does. Quesne’s background is in set design, from which he went on to found the theatre/performance company, Vivarium Studio, which produced the thing. It might be said he brought the studio to the stage at REDCAT; what he seemed to have left behind was the actual theatre and performance. The gimmickery—deliberately lame—was beside the point. There was no magic here. Not that I’m necessarily expecting drama, suspense, pathos, catharsis, comedy, satire, or even wit (or fill-in-the-blanks); but we should be able to expect something to happen: an event, a transformation, a change, a transaction beyond the ticket-tear at the turnstile. There’s more dramatic tension in John Cage’s 4’33”.

I liked that the Los Angeles Times’ theatre critic, Charles McNulty got the intended ‘amusement park’ aspect of the staging; but otherwise I had to wonder if we had even seen the same show. Frankly I think he was snowed. Artaud references? Give me a break – it merely underscored the pretentiousness of the whole business. “The courtesy depicted in La Mélancolie des Dragons makes it awkward to complain of dullness…,” he demurs. I have no such compunction. Dullness belongs on no stage whatsoever.

“The play’s the thing,” as Shakespeare (among others) put it; but it doesn’t have to be a ‘big’ thing. It doesn’t even require a stage. It can happen in the blink of an eye; it can happen on the street. You can stumble over or past it. It either registers or it doesn’t; but if it does, the action begins. The rest of the line is important, too: “ … [w]herein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.” On the street it operates at both levels: the state and its anonymous citizens, the passers-by. It’s an incitement to action, or simply a statement, but implicitly political either way. I’m talking about street art here – something that’s been with us forever, but taken on new importance since Haring and Basquiat transitioned from streets and subways to fine art main stages. In recent decades, its legitimation has expanded (not unlike fashion design) from private collectors and galleries into the divergent (but occasionally overlapping) domains of commerce and high culture (e.g., skateboard gear; museum shows like MOCA’s own Art in the Streets a few years ago). Many of these artists have extensive studio practices; the most successful are major enterprises; a few of them are art stars in their own right.

A few of those stars will be on view this evening at Julien’s in Beverly Hills – where they are being auctioned in two sessions scheduled for this evening and tomorrow morning. They include original work taken from actual street installations, as well as studio replications and multiples produced in studio and commercial lithography rarities. The best of them remind us (not unlike some of the highlights from MOCA’s 2011 show) how great some of this work is; also of its immense subversive power.

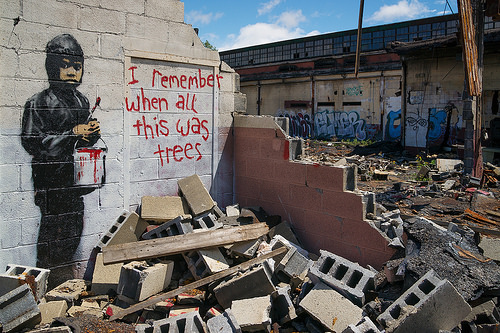

The largest and most significant of these installations are by Banksy. His 2010 installation at an old Packard factory in Detroit, I Remember When All This Was Trees, is here, complete with cinderblocks and broken two-by-fours from the original site. Another work, Donkey Documents, originally mounted in Bethlehem on the concrete barrier dividing the Palestinian West Bank from Israel, in which an armed Israeli soldier inspects a donkey’s passport, will be auctioned from London. (From its original siting, the Church of the Nativity could be seen in the distance, triggering the predictable associations.) But Banksy is not the only star represented here. L.A.’s own legendary Chaz Bojorquez is here (a beautiful layered, calligraphic work on paper); Shark Toof; and some truly outstanding works—both original installation panels and serigraphs—by Shepard Fairey. (I’m not exactly a huge fan of Fairey’s—and the ‘giant’ André’s charms are lost on me; but some of these pieces (e.g., “M16 vs. AK 47,” are wonderful—the best work of his I’ve ever seen.) The French are well represented here, too, by way of such artists as Ludo, the sui generis Space Invader (who practically transcends the category), JR (whose Women Are Heroes series of photographic prints mounted on tarps is already justifiably the stuff of legend), and Fairey’s famous French compatriot, Blek Le Rat. But even these scarcely graze the scope and depth of this rich selection. The vision of these artists is witty and wry; also bleak. Yet we emerge from these encounters not with mélancolie, but exhilaration.