Popular music is increasingly a topic of exhibition in the museum and gallery world but I’ve found its presentation can be either overwhelming or underwhelming. After all, how can the curator condense an experience so visceral like performance—an act itself at once singular and communicative—into a walk through display of objects? The Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles has managed to do just that, by approaching the subject matter in a very conservative curatorial manner.

Upon entering the space for the exhibition “Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution”—the first museum retrospective on the music industry figure—the guest is welcomed with the groovy sight of swirling colors projected onto the exhibition’s title. This act is foreshadowing the light show visitors will enjoy in the center of the exhibition. From here one can download an audio guide onto their phone, an act that is becoming standard practice in the museum world. What makes this one unique is that it is made up of recordings of Bill Graham (1931–1991), telling his own stories.

It is just one of the many aspects of this exhibition that made it feel as though I was walking into someone’s pop-up scrapbook. And though it was full of interesting relics from music’s past, it was never overwhelming; the show was completely intuitive and clean.

Graham was born Wolfgang Grajonca in 1931, the son of recent Russian Jewish immigrants to Berlin, Germany. In 1939 he was sent to France by his mother to avoid the Nazis and in 1941 he arrived in New York where a Jewish family from the Bronx adopted him. Graham dreamed of being an actor and moved to San Francisco where he became involved in the counterculture movement. He then became the manager of the San Francisco Mime Troupe. When the head of the group was arrested for his activism, Graham organized a benefit performance. Graham found his calling and went on to put on regular shows at the Fillmore in San Francisco and the rest is music and pop culture history.

Roy, Alfred, and Pearl Ehrenreich with Bill and their dog, Fluffy. Bronx, NY, ca. 1943. Collection of David and Alex Graham

The design of the exhibition understands that there are multiple cultures at play in this story: music, Jewish, American, counterculture, performance—all throughout the turbulent and ever-changing 20th century and yet, it is restrained. It is careful in its chosen objects and the way they are displayed in sections and themes with biographical notes, poster designs, photographs and rock history memorabilia. This display is ultimately realized as a representation of Bill Graham, much in the way one would present the work of a painter.

I was privileged to attend a preview of the exhibition led by the curator of the show Erin Clancey, where she described this approach: “I made an analogy at one point that if we were to do an exhibition on van Gogh, we might spend the first part of the exhibition talking about his history—where he came from, what influenced him—then we would show his work. For Bill his work was this music. It was about the whole presentation and experience of going to a concert, so when we chose objects we had to make sure that it was always coming back to Bill.”

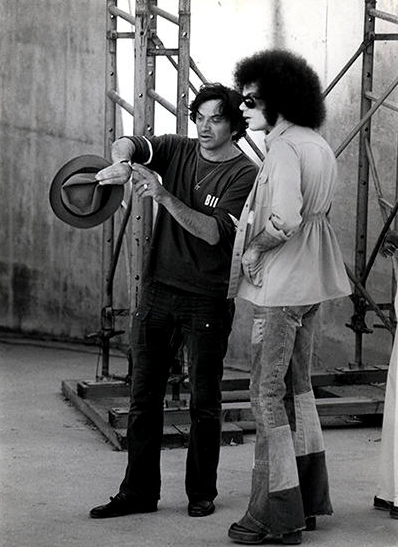

Bill Graham enlightens Beach Boys management: “Your band is late.” Oakland Coliseum Stadium, Oakland, CA, June 1971. Photo by Robert Altman.

In that sense we can begin to understand how the concert promoter was able to represent himself through the music. His skills as a storyteller were utilized through his live shows. “I suppose an analogy might be to a movie director,” Clancey said, describing Graham’s representation of himself. “You don’t see him on camera but he’s in charge of making what you see happen. He was the guy who got the musicians there, he gave them the right sound equipment, promoted it which ultimately created the concert going experience.”

View from the audience: The Rolling Stones at Day on the Green. Oakland Coliseum Stadium, Oakland, CA, July 26, 1978. Photo by Baron Wolman.

Walking through the exhibition I was amazed at just how much influence Graham had on the concert-going experience. How much he helped to foster the growth of many seminal acts of the 1960s including Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix and Carlos Santana. He also, most excitingly, initiated and produced Live Aid in the 1980s.

Bill Graham motions from backstage as Tina Turner and Mick Jagger perform at Live Aid. John F. Kennedy Stadium, Philadelphia, July 13, 1985. © Lynn Goldsmith

This exhibition expertly told the story of this man, the people he worked with and how he was instrumental in creating how we experience live concerts today. But ultimately, how he used popular rock and roll music to tell the stories he wanted to tell.

The exhibition runs at the Skirball Cultural Center until October 11, 2015 before traveling across the United States.