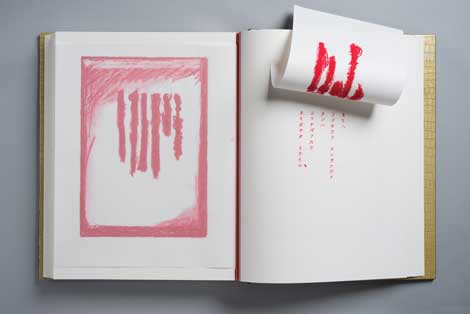

The 5th Yokohama Triennale closing ceremony ended with the burning of the specially created book, “Moe Nai Ko To Ba,” ironically titled “Words That Can’t Be Burned,” an homage to Ray Bradbury’s novel, Fahrenheit 451. This custom one-of-a-kind book was a centerpiece of the exhibition featuring collections of rare documents and visual work, printed by every imaginable mechanical and manual procedure and embellished in six languages; Japanese, Korean, Bengali, Thai, Russian and German. Heavily laden with quotations from condemned poet Anna Akhmatova’s spoken word under Stalin’s regime; ghostly hallway sketches of the evacuated Hermitage Museum during German air raids of the 1940s and the twilight-sleep mindscapes of Lieko Shiga’s photographs, the Book sat on a pulpit under supervised access (with gloves) and raised a few steps above the gallery floor. This last performance of the Triennale gestured to protest violations of freedom of expression, while subsiding in the requiem of all things lost, matter and culture.

Yokohama Triennale 2014 artistic director Yasumasa Morimura’s curatorial framework was arranged into 11 chaptered galleries housed in The Yokohama Museum of Art and Shinko Pier Exhibition Hall, loosely interpreting Bradbury’s dystopian theme and addressing global instabilities filtered through Bradbury’s apocalyptic vision. Situated dead center in the Museum’s main atrium, Michael Landy’s monumental Art Bin (2014) dominated the space, an inverted polycarbonate pyramid flanked by a stair ramp from which artistic failures were thrown in—a mocking reference to the derision with which contemporary art is treated, acted out in voluntary purging.

Leaving the giant dustbin, at the second level of the museum, the first gallery titled “Listening to Silence and Whispers,” proclaims Morimura’s yearnings for the vintage 20th-century avant-garde. As if resetting memory, Morimura’s introduction to the paintings and music void of color and sound, is plucked note by note—Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Drawings (Fragments); John Cage’s 4’33’’ (1953) original scores by David Tudor together with its copy; Josh Smith, Tomoharu Murakami, and Karmelo Bermejo’s monochromatic paintings. All of this rationalization arrives at a punctuation point in a dark corridor, where Marcel Broodthaers’ Interview with a Cat (1970) materializes into a stack of transcripts on a black table with a pair of stools. It was refreshing to leave the city limits of western hegemony into the adjacent gallery with graphic works by Yongik Kim (Korea) and Hiroshi Kimura (Japan) accentuating a semiotic comedy of art preparation, captioning and vivid color.

Ohtake Shinro, Retinamnesia Filtration Shed, 2014, @Shinro Ohtake, courtesy of Take Ninagawa, photo by Tanaka Yuichiro

In reference to the “exiles” in Bradbury’s novel, characters who memorize books and thus become books themselves as a means to preserve literature for posterity, Morimura elaborates his response in the consecutive galleries of the museum. Chapter 2, “Encountering a Drifting Classroom,” Kama Gei (established in 2012) is a nonprofit community project run by Kanayo Ueda whose concept, Cocoroom, is a free and open public classroom founded on the watchwords of “Voice, Words and Hearts.” The project addresses socio-economic conditions in former labor communities affected by waves of recession, with consequent issues of the elderly, unemployed, uninsured and homeless population. Kama Gei brings volunteer professors to offer workshops on various subjects, including philosophy, calligraphy, poetry, art and astronomy. Morimura himself is an active volunteer at Kama Gei, teaching and recruiting instructors from diverse fields of study.

The Triennale’s annex site, Shinko Pier Exhibition Hall, bookend to Morimura’s curatorial narrative is a remote portside warehouse accessible by the organization’s public transportation. The Triennale’s final chapter, “Drifting in a Sea of Oblivion” took place at this berth, harboring the behemothic stage trailer, Miwa Yanagi’s “Mobile stage truck for the play, Nichirin No Tsubasa The Wing of The Sun” (2014). Like the Japanese equivalent of “deco tora”(decorated trucks) and inspired by the phenomenon of the “Taiwanese cabaret”—a kind of traveling song and dance troupe stopping in public squares performing on the back of a truck equipped with lighting effects, sound, smoke machines, and karaoke functions, the trailer will embark on a nationwide tour of Japan as a stage prop for a production of “Nichirin no Tsubasa,” Yanagi’s newest theatrical project. This work is based on the original novel by Kenji Nakagami, a Japanese novelist who is the first (and so far the only) postwar Japanese writer to identify himself publicly as a Burakumin, a member of one of Japan’s long-suffering outcaste groups. His works depict the intense life-experiences of men and women struggling to survive in a Burakumin community in western Japan.

Tadashi Tonoshiki’s “Yamaguchi-Nihonkai-Niinohama, Okonomiyaki: Complete figure, weight about 2 tons” (1987), a massive assemblage of molten garbage collected from the Japan Sea coast, formed with the help of 130 volunteers, is a metaphor of its namesake, “okonomiyaki,” a savory pancake dish associated with Tonoshiki’s native Hiroshima, where he was exposed to A-bomb radiation at age 3. His work survived him by 20 years after his death. The 2-ton manmade tumor is a reminder and warning of catastrophes then and now—referencing the Tohoku Tsunami and Fukushima disaster of 2011. Another colossal assemblage, Shinro Ohtake’s “Retinamnesia Filtration Shed” (2014), is a “boat book,” manifested from ship scrap materials, thrift store discards of unidentified family photos and used machines, looming in the far end of the warehouse, anchored and waiting for a signal to set sail.

Descending the stair ramp of Landy’s Art Bin, Yasumasa Morimura holds his breath to answer my lingering question presented earlier in an interview with him. In the background, his large photographic print crumbles into the chasm of the art debris. “I miss the avant-garde movement very much. That is what seems missing right now.”

Since its inaugural event in 2001, the Yokohama Triennale, in parallel with the constant and unpredictable flux of world events, has progressively reinvented the social role of art in its collaborative programming. In 2004, the city of Yokohama launched the Creative City initiative, implementing an urban development plan for inner-city regeneration of defunct historical buildings, warehouses and suburban projects that were DOA in the burst bubble of Japan’s mid-’90s economy. The Yokohama Triennale is the core project in this undertaking. BankART Studio NYK, a spinoff art complex, similar to MoMA’s PS1, is a huge warehouse reused for multifaceted functions that are non-rental (very rare in Japan’s thriving rental gallery business), raising the platform for non-commercial projects including large-scale contemporary art exhibitions, artist residencies and consistent programs for exchanging artists between Taiwan, Korea and Japan with future plans reaching out to China and Southeast Asia. Based on the agreement at the Japan-China-South Korea Cultural Ministerial Meeting, a new project, “Culture City of East Asia” commenced in 2014, aspiring to foster mutual understanding among the three countries. Quanzhou, China, Gwangju in Korea and Yokohama are the designated cities of this pact. BankART is one of the cultural beacons taking part in this new virtuous experiment.

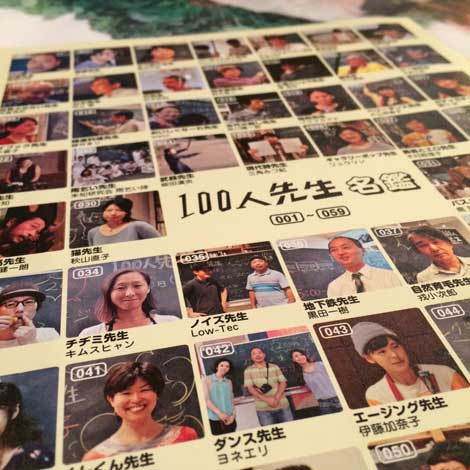

Osamu Ikeda, is the mastermind director of BankART1929. A regular contributor to the Tokyo Initiator’s Diary, he indefatigably drafts proposals for restructuring living spaces in available architecture, critically interrogating the relationship of artist and society. BankART’s program with the Triennale is BankART Life IV, “Dreams of East Asia.” In conjunction with integrating visiting artists from Korea and China, the primary objective is to connect local community projects involving eateries, public offices, social clubs, vacant lots, historic buildings and the city’s 150-year-old port through which western influences filtered into Japan. Yoshiaki Kaihatsu’s One Hundred Teachers Project for East Asia called out for artists and non-artists to conduct one-hour workshops about their unique and humorous field of interest; Hammock Teacher; Cat Teacher; Giant Fish Print Teacher; Noise Teacher and Rainmaker Teacher.

The diverse programming has enabled a surge of new artist-run spaces in the thriving nearby sectors of Yokohama Chinatown and Koganecho, a regenerated old red-light district. My curatorial project, “i:23,” received support from the Yokohama Triennale Committee, opened up extraordinary collaborations with new alternative and artist-run spaces in the area. Shichol Kim, a fervent gallerist and well-known chef, has opened AAA Gallery and Art Baboo 146 hoping to create affordable residencies for Korean and Chinese artists. Fred Verhoeven and his partner Ling Liu, recently transplanted artists from San Francisco, have also inherited a compact two-story home, converting the ground floor room for exhibition space.

Ikeda’s experience in resurrecting dead buildings is now allowing him to develop schemes for networking a series of abandoned factories in the Kawasaki-Yokohama border sector, establishing a permanent exhibit site for Japanese contemporary installation projects. His ambitions are on the scale of Spiral Jetty in Utah. One artist Ikeda holds in high regard is Tadashi Kawamata. In the project space of BankART1929, Kawamata’s Expand BankART (2012-2014) transforms environments, operating in the rift between demolition and construction either on a single house, apartment or reconfiguration of whole towns. His use of reclaimed wood produces unusual structures; a bridge between an apartment complex and a museum, a wooden walkway that leads from a town center to a lakeside, slum dwellings constructed in a picturesque park.

150 years after breaking Japan’s isolation from the outside world, opening to the West and now widening the aperture to the East, Yokohama continues its intermediary role as the beacon of intercultural affairs.