Last year, even as LACMA Director Michael Govan was in the midst of storing the collection off site so that demolition of older buildings could make way for the newly designed museum, he took the time to curate an exhibition featuring Pictures Generation artist Richard Prince. The show was a new iteration of the Marlboro “Cowboy” series that made Prince famous. For the original series made between 1980 and 2000, he had taken Marlboro cigarette ads from magazines, re-photographed them, and displayed them in galleries as his own art.

Although the exhibition closed months ago, it highlighted a strong relationship between Govan and Prince that is worth reflecting on. Prince continues to be in the news, with lawsuits over his use of others’ images. Because a museum director’s job requires diplomacy, discretion and at times deference, we rarely get a glimpse of the unalloyed enthusiasm for art that inspired him or her in the first place. Likewise, artists themselves are sometimes too intimidated by directors, especially on public occasions, to be entirely candid with them. But Govan and Prince have known and admired each other too long to have such inhibitions. The exhibition provided an occasion to observe that relationship up-close.

How close they are was apparent from the repartee that graced a public conversation they had in the galleries when the show opened. “I don’t see things the way other people see things,” Prince said at one point. “Clearly!” Govan exclaimed as he looked around the gallery walls. His quip got a laugh, which Prince then topped by remarking, as if speaking to himself, “I need to remember this for the deposition next week.” He was referring to one among the many lawsuits brought against him by commercial photographers who see his product as theft of their own works rather than a brilliantly original oeuvre.

Govan’s exhibition overtly addressed such controversy by including a video of Prince’s exchanges with his accusers, as well as displaying the Marlboro ads. In fact it seems that the photographers never owned the copyright to the images. Either tobacco company Philip Morris or Marlboro’s advertising agency, Leo Burnett, did. Nor did the idea of the cowboy originate with them. They were copying a 1949 Life magazine story about a real cowboy in Texas who was supposed to be the last of the breed.

In 1975, Prince had a menial job at Time magazine, cutting up issues to create tear sheets so that the articles could be sent to the writers who wrote them for their professional archives. Among the leftovers to be thrown away were the advertisements. These Prince began taking home, where he could photograph them. His ambition at the time was to be a painter. But, as he explained, “I used a camera because I didn’t have a studio, so I couldn’t paint, though I wanted to.” He found it satisfying to make these copy photographs; doing so was the one thing that made the whole process feel “real”. When he showed his copy prints of the Marlboro ads to colleagues, they thought he was the one who had photographed the cowboys in the first place. “I didn’t want to tell them that I took the pictures in my bedroom,” he says.

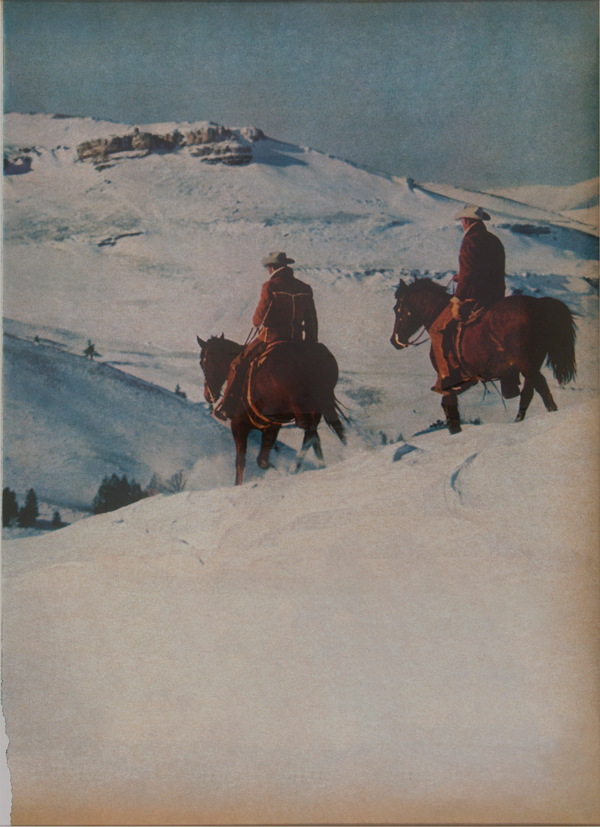

Richard Prince, Untitled (cowboy), 2016, dye coupler print, 82 × 60 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, anonymous gift, © 2017 Richard Prince, photo courtesy of the artist

Although neither he nor the art world at large knew it at the time, Prince was a member of what would be called the “Pictures Generation.” In 1977, the New York gallery Artists Space mounted an exhibition titled “Pictures,” which contained work by five emerging artists. One of them was Sherrie Levine, whose photography consisted of re-photographing work by earlier photographers considered great artists. Though not included in the show, Prince was already going a step further by re-photographing published commercial photography. And another fellow traveler not included was Cindy Sherman, who was creating from scratch cliché movie stills from fictitious B movies. Once the membership of the Pictures Generation expanded, these three exemplars held a special distinction as “Postmodernists”—artists who were using photography to argue that, in the contemporary milieu of Hollywood movies, mass-market magazines and 24-hour-a-day TV news cycles, it had become impossible to make truly original images.

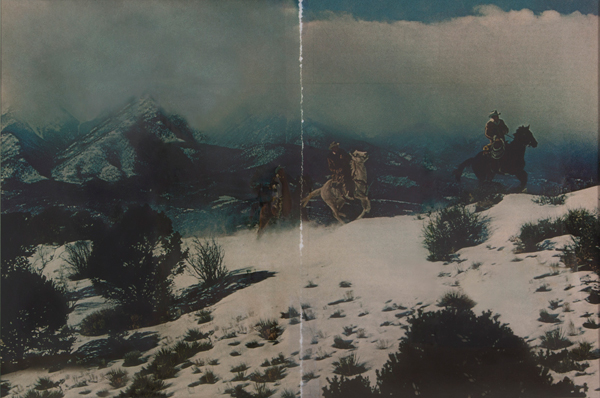

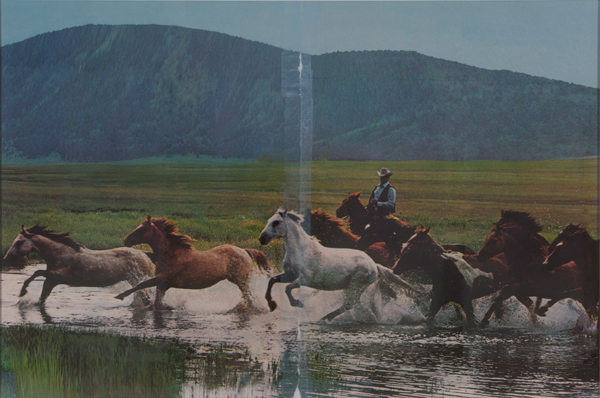

For the first set of the Cowboy series, Prince copied clean reproductions of the photographs in the Marlboro ads. The only tip-off that they were copies from magazines was that his enlargements revealed the grain in the reproductions. For the new series featured in Govan’s show, Prince had taken advantage of digital technology to make even larger reproductions relatively grain-free. Nonetheless, this time the source of the images is even more obvious because Prince seems to have used tear sheets for the enlargements that look as if ripped crudely from double-page spreads, with jagged edges where there are gaps in the middle, and Scotch tape added to keep the halves together.

What made the photographers of the original pictures mad enough to sue Prince was the fact that his knock-offs eventually sold as works of art for six or even (beginning in 2005) seven figures—considerably more than the commercial photographers had been paid to create them. I suspect that no one may be more surprised than Prince at what a coup he created with the Marlboro copies. Govan may understand better than he does how this came about. When I interviewed Govan the day after the opening, he said: “I was trained to be an artist, and I had a Conceptual bent.”

Richard Prince, Untitled (cowboy), 2016, dye coupler print, 59 1/2 × 89 3/4 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, anonymous gift, © 2017 Richard Prince, photo courtesy of the artist

Precisely because photography had a utilitarian side to it—from commercial photography to photojournalism—it was thought of as a minor art form compared to painting and sculpture. John Szarkowski’s first major exhibition as curator of photography at New York’s MoMA was “New Documents,” a 1966 show focused on three street photographers—Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus. It reinterpreted, but nonetheless extended, the idea that photography was a form of humanist photojournalism. Szarkowski’s chair at MoMA was called the “judgment seat” of photography. But in the 1960s, the Conceptualists staked a claim on photography that was more ambitious—and more audacious—than Szarkowski’s.

Conceptualists weren’t reinterpreting the history of photography itself, but, among other things, using the medium as a Trojan Horse from which to attack the recent history of painting. They used photography to undermine the heritage of Abstract Expressionism. “You want to see abstract?” they challenged. “We’ll show you abstract!” While Conceptualists used a whole range of media, an early, defining piece (one that was literally “defining”) was Joseph Kosuth’s 1965 One and Three Chairs, which consisted of a chair, a dictionary definition of a chair, and a photograph of a chair. From the late 1960s through the late 1980s, Vito Acconci, Douglas Huebler, and Christopher Williams each used photography as a strategic medium for their assault on the traditional idea of the “fine” arts. Photography was also key to the dissemination of site art created in remote locations where few would see the actual piece—installations like Robert Smithson’s 1970 Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake or Walter De Maria’s 1977 Vertical Earth Kilometer, a brass rod buried in the ground outside Kassel, Germany.

The most direct link between the Conceptualists and Prince, however, is Bruce Nauman. Nauman’s earliest work was photography of himself acting out cliché expressions like Eating My Words (1967), in which he is seen spreading jam on Wonder bread that has been cut to form the letters W-O-R-D-S. Such comic literal-mindedness is also characteristic of Prince, who befriended Nauman and wrote a piece on him published in his 2011 Collected Writings. There Prince analyzes Nauman’s interest in the 1954 movie Smart Alec, a porn film starring Candy Barr. Writing about pornography in the respectful tones heretofore reserved for high art is a deadpan form of subversion practiced by Prince, too. Conceptualism’s guerrilla warfare against the High Seriousness with which art had been discussed set the stage for Prince.

In a 1981 article in Parachute, critic Douglas Crimp argued that “photography’s reevaluation as a Modernist medium . . . signals the end of Modernism. Postmodernism begins when photography comes to subvert Modernism.” Conceptualism set the stage for this revolution and for the cue “Enter Prince.” Perhaps he was destined to fulfill his role, for he was born in the Panama Canal Zone, which is appropriated geography, much as his photography is appropriated art. Adding to this heritage is the fact that his parents both had subversive professions: his mother was in the Office of Strategic Services and his father was in the successor clandestine service, the CIA. Prince’s subversive career in art is redeemed from this shady background by the unpretentiousness with which he speaks of his art. His only touch of hubris is that he likes to make statements about his work that are intended to outrage—or at least disturb—even his diehard fans in the art world.

Richard Prince, Untitled (cowboy), 2016, dye coupler print, 59 1/2 × 89 3/4 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, anonymous gift, © 2017 Richard Prince, photo courtesy of the artist

In the LACMA exhibition, a separate gallery space was occupied by a mannequin of a little boy that Prince’s wife had bought for him and that he dressed up in cowboy clothes. Seeing it within the context of the show, it seemed an innocent enough inclusion, except that the artist couldn’t help comparing it to one of his most controversial appropriations, a nude photograph of Brooke Shields when she was 10, which he titled “Spiritual America.” During the exchange with Govan, Prince was unable to resist suggesting that Shields and the little cowboy “could be boyfriend and girlfriend.” His own fascination with pornography can go beyond Nauman’s and become a creepy obsession.

Nonetheless, even when Prince was off on a tear like this, Govan provided some ballast with his own side of the conversation. He’s interested in the Big Picture—how Prince fits into, and yet occupies a unique place in, the history of both photography per se and of art in general. With the exception of the space devoted to the history of the Marlboro ads, the exhibition had no wall texts of the kind that usually provide context for challenging work. When I asked him why, Govan said, “Just let the people look, bounce off the resonances of images. That’s the beautiful thing. You want people to go, ‘Hmmph’, and be quizzical, and then have to sort it out for themselves.”

A few years ago, Govan was so exasperated with what he felt was the conservative taste of LACMA’s Photographic Arts Council that he banished the group from his museum. “As I get older,” he explains, “I see that photography and photography collectors are a pretty distinct group. And I sense that there is a kind of tension, negative and positive, to Richard’s work in photography. He’s made so many breakthroughs in thinking.” Govan admires Prince because he challenges a traditional view about who can be admitted into to the canon of art photography’s history. “He’s not a trained photographer. He wants to be cagey, not to be captured by the culture of photography.” Although he respects and supports LACMA’s photography curator, Govan can’t help intervening in order to highlight his own take on the medium and his preference for “outsiders coming in like Prince.” Prince is now an established figure not only in the art world at large, but in the history of photography. Under the influence of Prince and other outliers who’ve reoriented how the art world views the medium, Govan observes, “Prices are rising, painting departments are collecting photography. It’s worked out well for the history of photography, because it’s still growing.”

Govan’s relationship with Prince is growing too. The bond these two have developed over a period of decades, at the expense of inherited conceptions of art photography, is too big and too significant to be contained in just one exhibition. Still, this show provided an opportunity for us to understand that relationship much better. Despite the persistent lawsuits (or perhaps with their help), Prince is now an established figure in the art world. In the age of the selfie that digital cameras have made possible, I’m reminded of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s contempt for such ubiquitous amateur imagery as “a million blasted moments.”

Crimp has, subversively, widened our sense of junk imagery. The way he has troubled us by dragging commercial photography into the art world is a testament to his insight.

0 Comments