Apocryphal notions, like northern superiority and European “discovery” of land already populated, pervade the Western Hemisphere. Even before Thomas More’s 1516 book Utopia, our so-named New World has been a locus for European fantasy projection. Currently on view at UCR ARTSblock, “Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas” showcases the work of artists employing science fiction as a means of questioning the status quo. Like More, but contrasting with his Anglo-centric viewpoint, these artists bestow imaginative visions of the existing world as metaphors for social and political critique. Themes of geographic, cultural, and social alienation pervade multifarious artworks ranging from small 2D pieces to expansive installations.

LA VATOCOSMICO c-s, The artist in his studio, 2016, with various works, 2008-16

Courtesy of the artist

LA VATOCOSMICO c-s, Decorated pants, 2016, Courtesy of the artist

Many of the 32 artists in Mundos Alternos use the limitless possibilities of the science-fiction genre to symbolically transcend borders or identity. In a similar spirit, the exhibition curators—a trio of ARTSblock director Tyler Stallings, Joanna Szupinska-Myers of the California Museum of Photography, and UCR English professor Robb Hernández, who specializes in science fiction—eschewed a geographic categorization of the artists, and instead thought about the show as a way to explore ideas based on sci-fi-oriented themes.

“Mundos Alternos” is divided into categories that suggest ways to consider timely social and political issues through novel lenses. Alien Skins, a category addressing morphing via attire, includes a fantastically painted suit that eccentric artist L.A. Vatocosmico (aka L.A. David) wears around his Texas barrio as a sort of performance. According to Stallings, Hernández was keenly interested in how “artists who could be identified as Latino or Chicano would change their own skin within their barrio or community.” These ensembles show how Chicano artists employ the transformative power of clothing, accessories and makeup to alter their physical and social identities, blending performance art and everyday life.

Hector Hernandez, Bulca, 2015, courtesy of the artist

Another Tejano, photographer Hector Hernandez, represents alienation and gentrification through pictures involving surreal costuming in works found in the exhibition’s Chicano Futurism section.

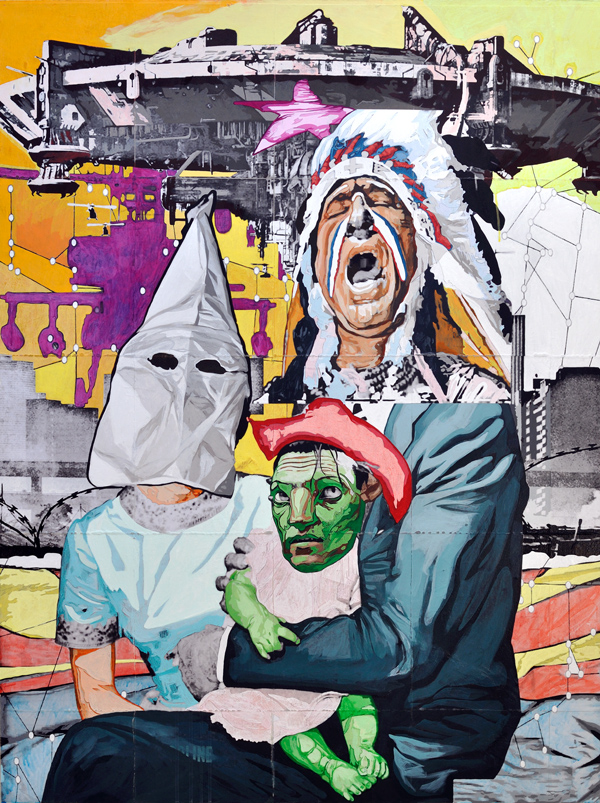

work by Claudio Dicochea

In the category of Information Control, Claudio Dicochea reworks colonial “casta” miscegenation paintings to investigate contemporary media’s perpetuation of caste systems. Dicochea’s strange, often humorous juxtapositions hybridize eras and cultures to question contemporary stereotypes—a commentary on how caste is “alive and well,” Stallings asserts.

Battling discrimination is a principal mission of contemporary indigenous revolutionaries in southern Mexico. Portuguese-born, San Francisco–based artist Rigo 23 conducts workshops with members of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Chiapas. Indigenous Futurism includes Rigo 23’s immersing maze-like installation created in collaboration with Zapatista artists. Their version of utopia involves a cornhusk spaceship piloted by snails symbolizing slow progress. Leading to the spaceship, paintings, baskets and other works created by these Chiapan artists adorn ramshackle walls evoking vernacular architecture of southern Mexico.

Also evoking exploratory wonder, Rubén Ortiz Torres’ kinetic sculpture Alien Toy (1997), is a border patrol vehicle/lowrider hybrid that mechanically disassembles within the exhibition’s “Post-Industrial Americas” section, which examines low-tech production as a means of self-empowerment. Alien Toy evokes the idea of a space exploration vehicle such as a lunar rover. Whimsical logos reading “Space Patrol” look like border patrol vehicle logos, furthering the title’s double entendre. This implied reference to space aliens slyly adopts the commonly used term for foreigners. Addressing issues pertaining to technology as well as immigration and borders, this sprawling, dynamic artwork blurs categorical, spatial, and technological boundaries. It also embodies aspects of Chicano Rasquachismo aesthetics involving biculturalism, reuse of everyday materials, and working-class sensibilities.

Clarissa Tossin, Transplanted (VW Brasilia), 2011, courtesy of the artist and Galeria Luisa Strina, São Paulo, photo by Edouard Fraipont.

Clarissa Tossin, Transplanted (VW Brasilia), 2011, courtesy of the artist and Galeria Luisa Strina, São Paulo, photo by Edouard Fraipont.

Car culture and cosmopolitism also figure in LA-based Brazilian Clarissa Tossin’s Transplanted (VW Brasilia) (2011), a detailed latex cast that appears as her car’s shed skin. Lying on a low pedestal close to the floor, this yellowish, flattened piece imagines a vehicle as its owner’s literal “third skin,” a metaphor for how automobiles are often viewed as surrogate versions of their owners’ personalities. Via allusions to the rubber industry, the automobile industry, and the car-oriented cities of LA and Brasilia, this piece also connotes the relationship between North and South America.

In Tania Candiani’s Engraving Sound (2015), viewers can tinker with an extraordinary soundboard where engraving plates act as records emanating otherworldly noise. Interactive pieces like this give the overall show a science museum feel aligning with its topic.

“Mundos Alternos” is accompanied by performances, a film series and a 160-page catalog including essays by the curators and sci-fi scholars. “The shared theme is that we’re dealing with social justice issues through the show as a whole,” Szupinska-Myers concludes. The work on display resounds with science fiction’s manifold capacities for surpassing mere escapism.