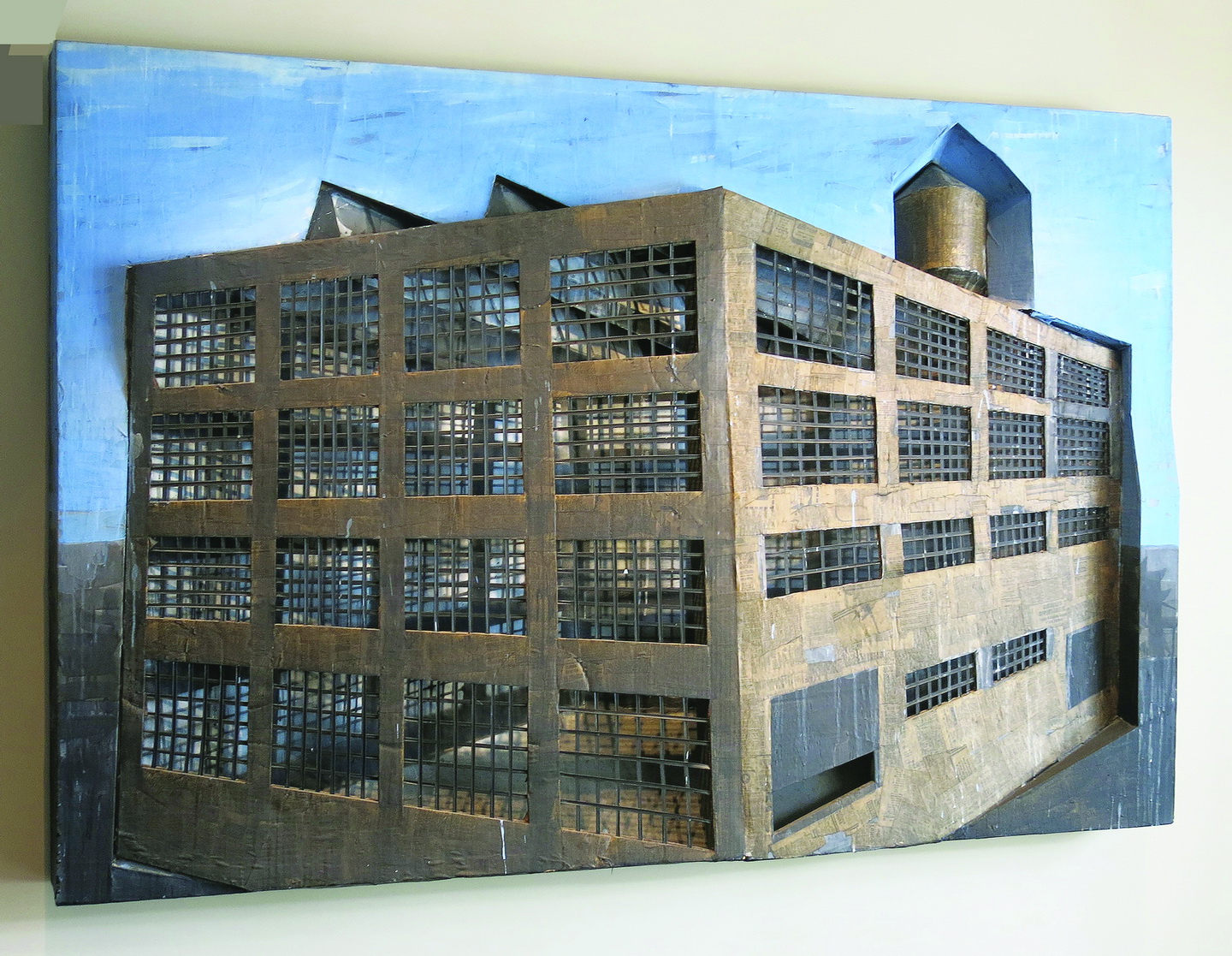

For over 35 years Karla Klarins has painted the built landscape, now presented in a survey exhibition entitled “Subdividing the Landscape.” In the early 1980s she gained attention for her expressive and unique sculptural relief paintings of downtown Los Angeles industrial sites in areas near her loft. The stark angular shapes theatrically thrust out from the flatness of the picture plane, and, in works such as A Loft on Mill (1980) with its empty cage-like projection and gloomy concrete coloration, they impart a Hopperesque or Munchian melancholy, suggesting the Bauhaus gone to seed. During this period, collaged newspaper cartoon figures seem imprisoned behind the windows of the newer downtown skyscrapers, mocking their function as power centers and subverting the sleek Modernist aesthetic. Window views of urban and suburban sprawl, with their masses of boxy low buildings reduced to loosely uniform abstract geometric grids beneath a horizontal haze, or scenes of boxy hi-rise constructions encased in queasy yellow and orange skies, are permeated with a similar urban angst. Domiciles fare no better, as the standard LA stucco house is often portrayed perched alone by the ubiquitous but strangely uninviting California pool, bordered by bleak fencing and devoid of personality and natural amenities, save the intermittent palm tree.

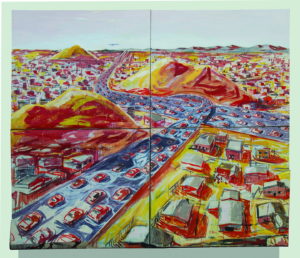

Karla Klarin, Drive Thru, 1996; ©Karla Klarin, courtesy of Aviva Covitz and California State University Northridge Art Galleries.

Klarins grew up in the San Fernando Valley in the 1950s when the city, fueled by postwar demand, grew exponentially. In the exhibition catalog she nostalgically describes her idyllic childhood of suburban meandering and her special admiration for an exotic pink “Sunset” modern dream house with a front yard paved in black geometric shapes instead of grass that is the subject of her 2014 series “Natalie’s House.” Southern California was a hotbed of unbounded architectural experimentation, distinguishing itself with John Lautner’s Chemosphere House, Eichler’s populist streamlined Modernist dwellings, futuristic shopping centers, museums and music centers. British cultural and architectural critic Reyner Banham’s The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971) idolized LA as an exciting blend of beach, flatlands, mountains, and freeways—“some of the greater works of man”—promoting an exhilarating, until then unexperienced, freedom. Klarins’ Drive Thru (1996) with its blood-red, sunset/fire–tinted, car-clogged freeways reaching from the foothills to the ocean is a much less enthusiastic evocation of unbridled movement and development.

Banham’s sunny view of uncontrolled growth and land predation seems to have never anticipated the problems facing 21st-century megacities. Klarins’ “Natalie’s House” series implied as much. In a blend of figuration and abstraction, painterly fields of intersecting lines filled with brushy and knifed black, white and gray geometric shapes and shards surround an architectural-style drafting of the pink house. Her “Rosebud,” and other houses on the street, are reduced to the phantom forms of a paradisiacal memory. Midcentury optimism—à la Diebenkorn’s beloved Ocean Park impressionism, and Hockney’s cheery drives through the hills in the 1990s—are now transformed into a ruined landscape of crisscrossing black lines and ashen colors in Big Pink L.A. (2016). Progressing to pure abstraction with imagery disintegrating into painterly swatches and hints of a pinkish brown smoggy sky over the unbounded city grid, Klarins now veers into the terrifying sublime, recognizing, as she always has, the dark side of utopia.