I’d taken a photographer friend to The Getty to look at the Light, Paper, Process show curated by Virginia Heckert – a must for any photographer and, for that matter, for anyone interested in process-oriented form and media (which includes myself, in recent months). My friend’s work involves considerable compositional and chromatic manipulation and intervention in her entire process of creating a finished image, as well as a certain meticulousness in her use of materials; and it was interesting to compare notes and hear her specific appreciations of some of the artists. Walking through it a second time also rekindled a fascination with the way several of the photographers’ engagement with earthly and cosmic phenomena paralleled their engagement with the entire process and the medium itself; at its furthest extremes (e.g., Lisa Oppenheim, Chris McCaw). The process itself becomes a kind of gestural recapitulation and reenactment. Our interposition of a means of recording this natural or elemental trace inevitably changes our relationship to and perception of it.

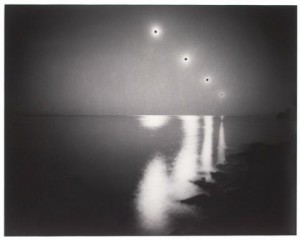

Oppenheim dramatizes the process still further by almost diaristically recording the various exposures of these phenomena (sun, moon, smoke—themselves vintage negatives taken from 19th and 20th century sources), including interruptions – when the negatives weren’t exposed at all – a visual absence, pause or silence that underscores the ‘sound,’ or ‘mark’ of the interaction. Oppenheim’s education in semiotics and background in structural/materialist film clearly informs the work (as curator Virginia Heckert’s points out in her catalog essay for the show). The photographs ‘read’ on several levels simultaneously, functioning as cultural, even political commentary, and placing the viewer/observer in an ambiguous relationship to subject, time and placement. The smoke of the documented explosions – a World War II bombing raid over Normandie – might read as clouds, also as the (exploded) earth itself; the aircraft – the instrumentality of this action and document – lost amid sky, clouds, smoke.

The fundamental changes in perception and subject-object relationships are borne out still more dramatically, yet contemplatively in John Chiara’s – I hesitate to call it – ‘landscape photography.’ Chiara is quoted in the catalog, insisting, “The subject of my work is Photography itself. Its manifestation through its means.” But the choice of words here is as revealing as the photography is alternately dramatic or contemplative: ‘photography’ with a capital P, the writing, inscription, mapping by means of Light; the ‘manifestation,’ as in the reveal, what is disclosed and made manifest. The resulting photographs hardly need theatrical amplification. Chiara’s intensively hands-on process – incorporating both in-camera (direct on photo-sensitive papers) and darkroom techniques – has yielded truly breath-taking imagery that richly document both the artist’s physical (and psychological) trace and the passage of time and elements.

If I thought my second view of the Light, Paper, Process show would be somewhat more cursory than the first, I was clearly wrong. I’m sure I spent as much time with each photograph (or photogram) as I had the first go-round. But my first priority that day was the magnificent show of Hellenistic bronze sculpture, jointly organized by the Getty Museum, the National Gallery and the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World. Again – not to discount in any way the power of the sculpture itself – the title conveys so much: specifically the word, Pathos, which after all comes to us directly from the original Greek. Its fundamental power was recognized almost from the moment it was expressed. The original meaning itself connotes expression, its roots related to both suffering and experience – subordinate in classical rhetoric only to logos, the word itself, the power of logic. (The other ‘mode of persuasion,’ in Aristotelian terms, being ethos – the fundamental ‘character,’ guiding beliefs, ideals, etc. of society and state.) It would be absurd to dredge up Aristotelian rhetoric to sum up a show of this cultural, artistic, and emotional scope. But in a way, we can see an argument unfolding here – an assertion and demonstration of what it means to be human in the centuries between Alexander and the Caesars; an individuation of human character beyond social, biological, or religious function, beyond the functional or ideal forms of gods, heroes, athletes, soldiers, rulers, law-givers and rulers, to something approaching character, personality, type, psychology, even style. Moving from idealized portraits of Apollo that would become the template for classical portraiture through the High Renaissance, to figures like the “Arringatore” – which would not be out of place in a line-up of Republican presidential candidates – to the penultimate galleries, where the scarred, seated “Terme Boxer” seemed to contemplate his more youthful incarnations, we trace an evolving humanism, but also clarity regarding the frailty, weakness and vulnerability of the species.

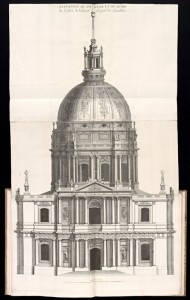

It could not have been more of a contrast to the show we moved on to at the Getty Research Institute galleries – A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660-1715 – the propaganda function of which might be summed up as the promotion of the Sun King and his power (and by extension France itself) to sky-filling Apollonian glory. This was a project that required more than filling the swamps of Versailles (the taming of nature is an important theme in this campaign for hearts and minds). It required great strategy, style, and art – but that will have to wait for another post.