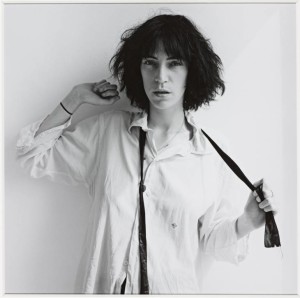

Patti Smith (1975), gelatin silver print; courtesy The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Fresh (if that’s the word for it) from the carbon cycle conundrums posed by the FotoFest 2016 Biennial in Houston, I faced the ambivalence of ‘homecoming’ between LACMA and the Getty Museum, returning to, if not the ‘haunts’ of my mole-dark youth, certainly a few of its ‘hauntings.’ The world Robert Mapplethorpe documented between the 1970s and 1980s was in part my own: New York-steeped, sexually misfit, aesthetically preoccupied. And then there was Patti Smith – with whom I was obsessed even before Horses debuted with a cover portrait that might have been pulled from one of my own family photographs. Yet however familiar, a large part of this world was unapproachable – even close-up. I can recall a gallery event Mapplethorpe attended in San Francisco. (Or was it a sex club made into a gallery space for the evening? – the experience was that blurred.) ‘Ya gotta go,’ all my pals said; and – not being one to let the team down – naturally I went. There was a lot of leather – in the photographs and on the bodies clustered in the small rooms of this gallery – so much so, I can’t specifically recall most of the images (though I recall bullwhips in rectal terrain). Finally I managed to squeeze through an opening into a corner room, where a small throng of muscle boys clad head-to-toe in leather, everyone of them smoking, parted just enough for me to see Mapplethorpe at their center, posed in a kind of James Dean slouch with a Dylan-esque ‘I’m-not-really-here’ expression on his face, clutching a cigarette of his own. He might have been a hologram. Here was an artist who might be pierced (and photographed), but could not be touched – not that night anyway, under what looked like a mushroom cloud of tobacco smoke. I retreated while I could still breathe; and wouldn’t revisit this world until Catherine Opie’s slightly female-friendlier (and not quite so claustrophobic) version of it.

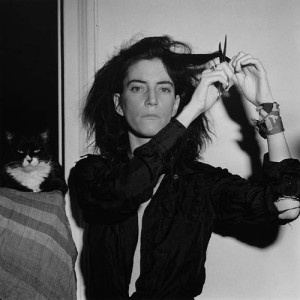

Patti Smith (1978), gelatin silver print, courtesy LACMA

You can’t go home again; but there’s no abandoning it, either. Instead, we build small shrines to it – little dark places, perpetually lit by the wavering lights of our devotions and regrets, and the smoulder of secret shames. I’m probably overstating it a bit, but there is that element in Mapplethorpe; and I was delighted to see that the LACMA exhibition included a gallery given over to non-photographic work, including, in addition to some very durable and beautiful drawings, collage and assemblage pieces (with bits and pieces, drawn from magazines and commercial products, very much in Pop’s shadow, though with a fetish twist), as well as jewellery, personal objects, effects and ephemera. And an actual shrine: actually this was an untitled sculpture/assemblage, with the parenthetical title magnifying its religiosity – Altarpiece. It includes an actual Jesus statuette (along with a faded image, beneath a lampshade ‘baldachin’) – no doubt a more forgiving Redeemer than we were likely to encounter at St. Patrick’s. Kyrie eleison. But how distant really is the notion of religious veneration from sexual fetish? Counter-Reformation anyone? Go ask Saint Theresa – or Bernini’s version, anyway.

Flower with Knife (1985), platinum print; courtesy LACMA & J. Paul Getty Trust

Mapplethorpe was looking for more than mere ‘redemption’ in his work and ambition. He wasn’t going home – which can never be far enough away for a sexual outsider; he was going downtown. There’s a kind of articulate magic-making at play in both the photographic and non-photographic productions, an alchemy of light and dark. Consider for example (in addition to the aforementioned Altarpiece), an untitled construction with a small cylindrical cage of dice (in various sizes), a leather-gloved and braceleted mannequin hand, and rabbit’s foot linked to something that looked vaguely like part of a hand-cuff. (And there are so many other examples.) Even in some of the earliest black-and-white photography (Patti Smith obviously figures in some of these), there’s a deliberation in the composition of light, shadow, pose and setting – not the ‘decisive’ moment exactly, but a moment when the magic might be triggered. There was a fugitive glory at stake here.

Joe, NYC (1978), gelatin silver print; courtesy LACMA

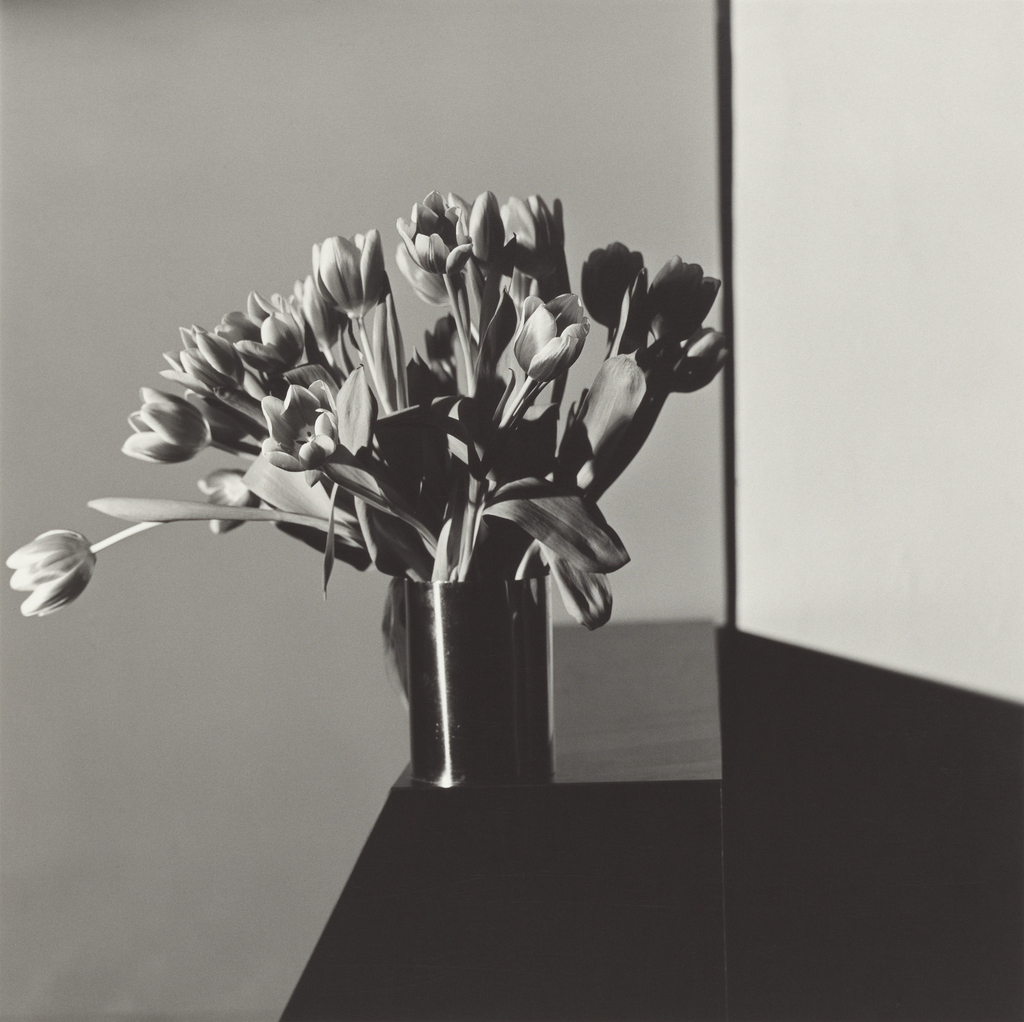

Parrot Tulips (1988) dye imbibition print; courtesy LACMA & J. Paul Getty Trust

The sense of control, both mental and physical, is almost palpable here – and that’s part of the pleasure. It was inevitable that Mapplethorpe should turn his camera on the not-very-far-underground world of sex clubs and S/M dungeons where the instruments of control and pleasure might be one and the same, where conventional dialectics of pride and shame were reversed or entirely subverted. (Who says we can’t have our quality of mercy strained through a pound of flesh?) It’s easy to understand why the performance artist, Lisa Lyon, one of the original women bodybuilders (and certainly the most beautiful) would have captured Mapplethorpe’s eye. The aspect of gender-role subversion could only be the most superficial part of the attraction. More compelling is, once more, a ritual of control and release; the tension between strength or potential energy and physical exertion or applied force; also the tension between what is veiled or concealed and what is revealed or exposed to light. (No cropping needed here.) Again, the deliberation – in pose, in props – is striking: the veil, the hat (the boot, the harness; cut or uncut).

Lisa Lyon (1980) gelatin silver print; courtesy LACMA

The veil might be Mapplethorpe’s dominant visual metaphor; he veils with light and shadow in equal measure. He’s drawn to beauty, and always finds means to plumb fresh forms and aspects (consider, e.g., his gorgeous color screen prints and dye transfer prints of mostly floral subjects); but holds a discreet distance – sic transit gloria mundi – destined to disappear like all vanities before it.

Lisa Lyon (1982), gelatin silver print, courtesy LACMA & J. Paul Getty Trust

Like any great artist, he knew how to steal from the best. We see the influence of many great predecessors here: André Kertesz, Irving Penn, George Dureau, and especially Hoyningen-Huene. It’s almost surprising not to see more fashion and music-related commissions. (One of the Lyon/Lady photographs is strikingly reminiscent of a Huene Vionnet sitting.) His influence was evident in the commercial music world (e.g., David Bowie, Iggy Pop). But time was not exactly on his side; by the time the fashion world might have seized upon his vision, he was already in failing health. Those color studies and screen prints, with their gorgeous color geometrics and beautifully raked with shadow, give some indication of where he might have taken his art. This is where control has finally taken him – that fragile but transfigured intersection of medium and moment.

Poppy (1988), dye imbibition print; courtesy LACMA & J. Paul Getty Trust

0 Comments