AWOL is in Houston this evening – with official leave this time (at least in theory, still leaving no accounting for her invisibility the last two or three weeks in Los Angeles) – at the 2016 FotoFest Biennial. The theme of this year’s Biennial is Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet; and there was a fatalistic undertow to some of the conversations among artists, curators and spectators at the Biennial’s opening night reception at Silver Street Studios in what has become known as the Washington Avenue Arts District of Houston. This is not the first time the Biennial has addressed environmental issues in its organizing theme. Executive Director Steven Evans pointed to at least three biennials between 1994 and 2006 that mediated similar dialogues of art, science and technology, and culture and society on the global environment. (The 1994 edition was actually titled The Global Environment.) But the strong work exhibited at the Silver Street Studios – which also functions as FotoFocus’s headquarters – brought a focus of unusual clarity to the urgency these issues have accrued in little more than two decades. The ‘risk society,’ as Evans might characterize it, citing Ulrich Beck’s seminal study of technology’s impact on culture and society, has given way to an ‘at-risk’ planet, with planetary life itself imperiled.

A viewer might easily draw a tentative conclusion that the six artists exhibited in its airy and beautiful space, were presenting both the ‘kernel’ of an argument for the preservation of the planet and its biodiversity (almost literally in one instance) and a poetic archaeology of its decline. “Everything is connected,” was the theme that resonated through the exhibition – echoing ideas treating the Earth as a living organism first eloquently articulated in the work of Alexander von Humboldt, which has received fresh attention in Andrea Wulf’s stunning new biography of von Humboldt, The Invention of Nature; and the work of these six artists explored an entire spectrum of these ideas from micro- to macrocosm.

Susan Derges, Eden 7 (2004), unique dye destruction print, courtesy the Artist and Purdy Hicks Gallery, London

The sense of physical connection was palpable among the works seen in the Silver Studios space; yet also a sense of alternately rational and entirely random, irrational displacement. A common thread was the mapping or inscription upon terrestrial surfaces. The English artist, Susan Derges, was represented by her celebrated cameraless studies of the ebb and flow of water, riverbed debris, flora and fauna rippling across the River Taw, registering in various degrees of color and luminosity from cyanotype blue and turquoise green to amber and blush muddles of light – which nevertheless evinced greater sensuality than her more polychromatic Tide Pool studies – presumably teeming with life, yet floating abstractly here in their tondo frames. Nowhere was the sense of geological inscription more stark than in Jamey Stillings’ black-and-white studies of the Ivanpah Solar Project, with views of the installation’s sharp-edged, almost perfectly geometric perimeters etched into the Mojave Desert terrain. With their massed arrays of reflective heliostats offset against the undulant, alluvial terrain of the untouched desert surrounding them, they took on an almost heroic (or tragic) aspect, evoking variously, Heizer, Smithson – and native American earthworks. Even in the composition of more documentary photographs, the viewer felt the contention of natural (and unnatural) forces, framed and offset by the camera’s positioning and the heliostats’ reflective surfaces.

Jamey Stillings, from series, “The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar,” 2012, archival pigment print

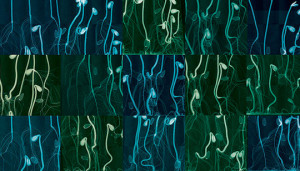

Dornith Doherty, from Archiving Eden series (2011), digital chromogenic lenticular photograph

The framing of Dornith Doherty’s work – mostly taken from her on-going Archiving Eden series – is even more deliberately conceptual, almost clinical, but to an end no less sublime than Stillings’ aerial geo-tragedies, and with an uncanny poetry and elegance. The crisis of biodiversity has not gone unnoticed by governments and major universities and scientific institutions, which have collectively mobilized (and centralized) resources for the preservation of critical and threatened plant species. (These include, for example, Norway’s Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Kew Gardens’ Millennium Seed Bank, and USDA facilities scattered everywhere from the mid-Atlantic to Alaska.) Doherty was given permission to photograph x-rayed seeds, sprouts and seed clones and adapt them to her own purposes.

Dornith Dohery, Sunflowers (2009), from Archiving Eden series, digital chromogenic lenticular photograph

Doherty has variously assembled, isolated and digitally collaged these x-rays into grids, specimen arrangements and single specimen studies presented in pigment prints or large chromogenic lenticular photographs. The lenticulars emphasize the aspect of subtle metamorphosis in the sprouting seeds, while underlying colors (cyans and indigoes, yellows veering into amber) convey the sense of suspension, hibernation, the timeless netherworld of these laboratory facilities. Without getting ‘Full Frontal’ about it, there was an aspect of some of the lenticular pieces that that couldn’t help reminding me (and I’m sure others of a certain generation) of the kinds of compartmentalized seed, specimen and souvenir shadow boxes that poured out of craft and gift shops in the 1970s. I confess that I’m getting bored (or simply exhausted) with the grid, regardless of subject or motive. But Doherty’s were exceptional in every sense – evoking the rhythm, music, magic and mystery of her subjects. Her isolated specimen studies and arrangements, which have a calligraphic elegance, are masterworks of the form.

Dornith Doherty, Pair of Wild Seedlings (from Arichiving Eden), 2015, archival pigment print

There was documentary material (inclusive of photography) – with eloquent and thoughtfully placed wall text – throughout the space. Still, a viewer might pause before considering the color tondo prints by Luis Delgado-Qualtrough presented in their folio pages – easily some of the most delicately subversive work in the Biennial. (And by the way, not all of it photographic.) The photographic prints, which appeared more or less centered at the top of their respective pages, were mostly skyscapes or atmospheric studies – images that might not be out of place in scientific or meteorological journal of a certain vintage, and with a similar charm. The pages are presented as “Coincidental Observations,” with titles like, “Burning Dinosaur Bones,” “Seven Sisters,” “Manifest Destiny,” and “The Birds and the Bees,” (a few specifically linked to the Biennial’s Changing Circumstances planetary theme. Although some of the texts are relatively straightforward, factual or anecdotal, they present, in conjunction with the images and facing pages, a wryly elliptical, almost Dada aspect: Lautreamont or Apollinaire meets E. O. Wilson meets Glenn Seaborg or maybe Werner Heisenberg. They’ve been compiled into a book, fittingly titled 10 Carbon Conundrums – and Delgado-Qualtrough has managed to weave a great many scientific, historical and cultural truths into these enigmatic tales, from carbon cycles and benzene rings to the degradation of the biosphere’s vital balance.

Luis Delgado-Qualtrough, “For As Long As the Water Flows,” from 10 Carbon Conundrums, 2015 (Malulu Editions)

Rounding out the Silver Street Studios component of the exhibition were works by Karen Glaser, who is known for her studies of the aquatic environment and the blurred divide of phenomena above and below its surfaces; and Gina Glover, who has documented the stark encroachments of industrial civilization – and in particular the fossil fuels industry – on the environment. I don’t mean to give short shrift to these artists and their work; but in this beautifully installed and laid out section of the biennial exhibition alone, you can see where FotoFest 2016 is headed: an organically integrated, multi-dimensional view of what the human eye and hand have made of the world, and where they might take us.