ART/VERSE

Kick the Can by Maw Shein Win That utopian moment when the film begins & the sound spins, awash in honey & blood, saliva & wine. Let’s kick the can! Alive in the eye of projection, variations of pink on aqua. In Icelandic they say “invisible.” In Spanish...

IN THESE TIMES

It’s Too Hot Not to Cool Down, 2017

SHOPTALK

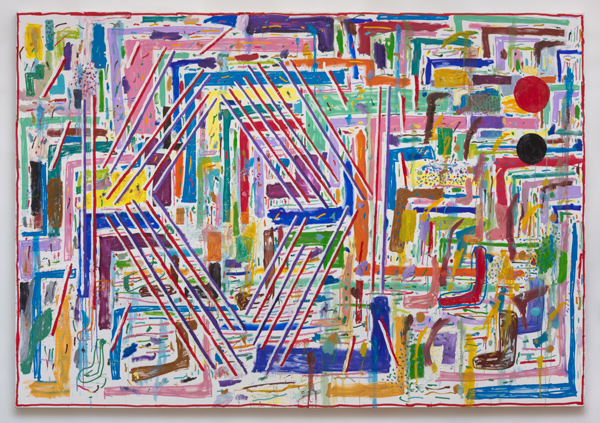

NEW MUSEUM IN TOWN Welcome Marciano Art Foundation on Wilshire Boulevard! It’s the new museum that features the contemporary art collection of Paul and Maurice Marciano, two of the brothers who founded the hip jeans company Guess and became zillionaires. The museum...

RETROSPECT

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1982 Untitled painting of a skull looks like a prison that can barely contain all the rage, anger and fierce memories that drive a person. Painted in graffiti style, it is young and barely controlled. You wonder how it is ever going to get...

Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle

The figures are in motion, contorted, double-jointedly bending over themselves—so confused with playing multiple roles that a single, consistent identity becomes, at best, elusive and in its most virulent form, theater of the absurd; a brand of schizophrenia that...

Star Montana

In exquisite large-scale photographs, figures of hope, variously tinged with the pain of day-to-day reality, exude optimism, gazing upward and confidently looking straight at the camera and viewer. The portraits in Star Montana’s “I Dream of Los Angeles” punctuate the...

Women of Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionist painting remains one of the most pivotal and enigmatic art movements of the 20th century. Its continued influence on current abstract painting can be seen in the work of the best practitioners such as Albert Oehlen, Yayoi Kusama and Frank...

Chris Antemann

The term forbidden fruit nowadays refers to mere guilty pleasures, but it once designated the fatal, tragic fruit of knowledge—knowledge of sex, or course, being a discovery that every generation makes defiantly, with mingled trepidation and delight. Chris Antemann’s...

Richard Deacon

Forty-three works in an expansive range of media highlight Richard Deacon’s versatility in a broad yet uneven survey of the British sculptor’s art from 1979–2016 in “What You See Is What You Get” at The San Diego Museum of Art. Deacon’s austerely lyrical...

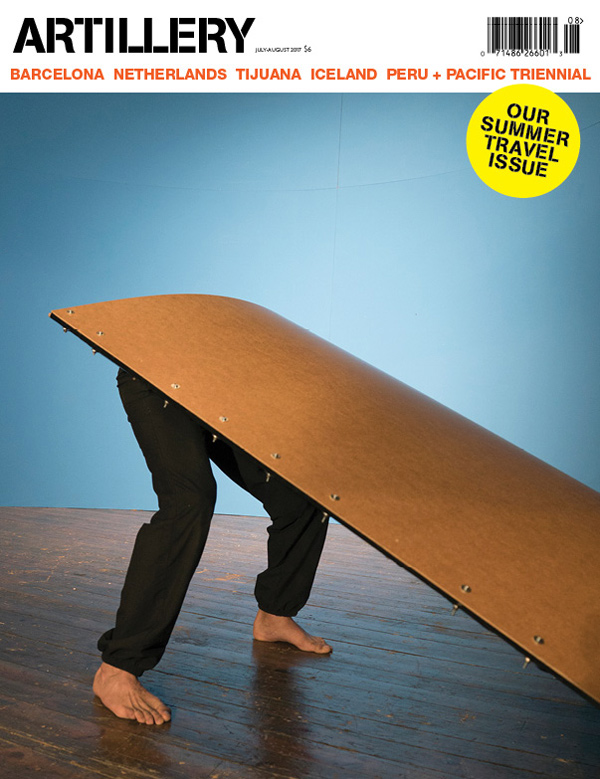

ON THE COVER

Teresa Solar Abboud, Untitled, 2017, detail photography from her “Ground Control” solo show at Galeria Joan Prats in Barcelona; part of our Summer Travel Issue where contributor Leanna Robinson visits Barcelona's underground art scene....