“Building As Ever,” the 2017 California-Pacific Triennial at the Orange County Museum of Art, investigates the economic, political and social forces that affect the built environment. Themes of gentrification and dislocation, meditations about home and displacement, and discursive considerations of architecture emerge in works from 25 contributors, who live and work in 11 countries along the Pacific Rim. Many of the exhibitors are trained architects, and the contributions blur distinctions between art and architecture.

Estudio Teddy Cruz + Forman, the political/architectural practice of architect Teddy Cruz and political theorist Fonna Forman, produced Mecalux Retro-fit: Framework for Incremental Housing (all works 2017). Adapted from industrial shelving produced in a maquiladora in Tijuana, Mexico, Retro-fit is a small-scale, flexible structure that can function in a variety of uses, including housing. ETC+F position Retro-fit as a low-cost solution for the bedroom communities of Tijuana that house Mecalux’s workforce.

Displacement figures in The Community/The Museu, a series of photographs, DVDs and didactics from Nancy Popp, in which she documents the struggles of the Rio de Janeiro community of Vila Autódromo to resist eviction in advance of the 2016 Summer Olympics. Also addressing displacement and discrimination in Southern California, Pilar Quinteros’ China House Great Journey documents a durational performance with a video projection and wood model.

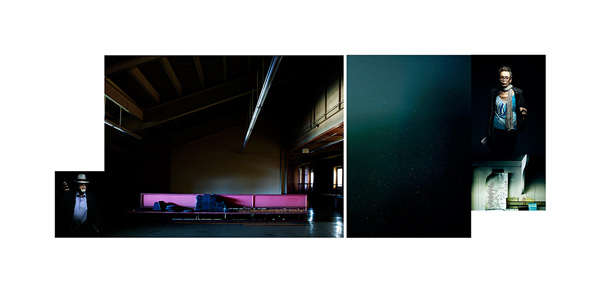

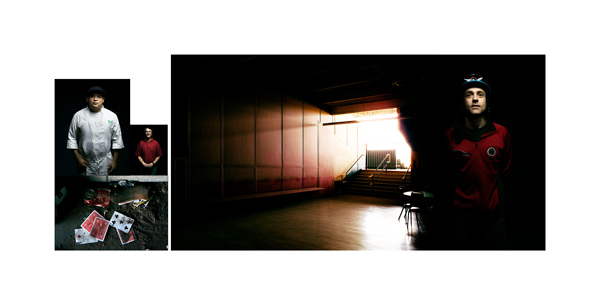

Michele Asselin, Clubhouse Turn – Composition 2 (Dave; North End Bench; Horsemen’s Lounge Wallpaper; Sandra; Phone List; Media Room), 2013 – 16. Five archival pigment prints with artist’s frame. 38 x 106.5 in. Courtesy of the artist and OCMA.

Michele Asselin, Clubhouse Turn – Composition 8 (Samuel; Saul; Playing Cards; Exit to Grandstands; Iggy Puglisi), 2013 – 16. Five archival pigment prints with artist’s frame. 38 x 99 in. Courtesy of the artist and OCMA.

Other projects explore similar territory. Alex Slade’s photographs identify building projects in Los Angeles produced by an influx of foreign capital. Michele Asselin’s elegiac portraits of the defunct Hollywood Park recall Roland Barthes’ assertion of photography’s memorializing function. Haegue Yang’s An Opaque Wind—Humbled Gray #2, a sculptural assemblage of ubiquitous materials, addresses the endless building cycle, and the digital prints and video installation series the story of my early life by another mountainman (Stanley Wong) document abandoned spaces in Hong Kong.

Beatriz Cortez, The Lakota Porch: A Time Traveler, 2017. Welded steel, sheet metal. 144 x 192 x 96 in. Courtesy of the artist and OCMA.

Home seems transcendent in Lakota Porch: A Time Traveler, Beatriz Cortez’ magnificent life-size welded steel and sheet metal reconstruction of craftsman vernacular porch. The materiality and craft in Cortez’ work finds echoes with Trong Gia Nguyen’s reproductions of French colonial architecture window grates from Vietnam and Cybele Lyle’s meditative wood plank, sound and video installation.

Trong Gia Nguyen, Double Rainbow, 2017. Oil on wood. 46.5 x 46.5 in. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Quynh, Ho Chi Minh City, and OCMA.

Nguyen’s oil pastel and photo-collage works embody personal memories attached to home. This reminiscing about place comes fully into play in Patricia Fernández’ installation And Still (facing north), and other works, that include photos, watercolors and ephemera; they represent a history, to which Fernández is inextricably linked through her father, of the exile Spanish printing press Ruedo Iberico, during Franco’s regime.

Patricia Fernández, And Still (facing north), 2017. Beechwood staircase with aluminum poles, porcelain, Ruedo Ibérico books, French newspaper, stamp, photographs, and watercolor drawings. 108 x 66 in. Courtesy of the artist and OCMA.

Yuki Kimura’s installation, Wardrobe Extensions (Version 3), similarly represents objects as personal touchstones. Olga Koumoundouros moves this idea into the realm of institutional memory as oral history, with her installation, Neither Liquid Nor Solid But Amorphous; differently ordered bodies flow under large stresses, creep or remain stationary under smaller stresses, and have complex, history-dependent behavior. 1 (2017), which is a kind of memorial for a janitor who passed away on the museum’s premises.

Yuki Kimura, Wardrobe Extensions (Version 3), 2017. Site-specific installation. Three reclaimed wardrobes, 35mm color slides, projector, DVD, monitor, framed C-prints, mirror, glass, metal, and benches. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, and OCMA.

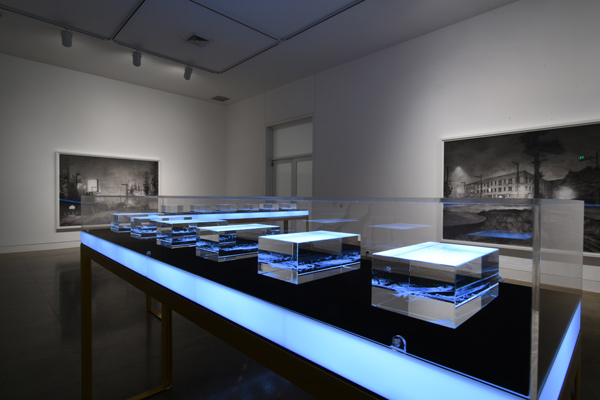

Lead Pencil Studio (architects Annie Han and Daniel Mihalyo) addresses land use and transportation systems with Void Promise: Last Tract A and Void Promise: Last Tract B. Each piece is a set of six lead crystal blocks etched with scale models of Southern California parking lots. While the medium evokes wealth and exclusivity, these exquisite landscapes conjure thoughts of heat islands, pollution, traffic congestion and consumer culture. Less convincing, LPS’s works on paper could depict locales ranging from Northern California to British Columbia; juxtaposed with the etched lots, they seem fictitious and anonymous. Contrasted with the luxury of the lead crystal, Carmen Argote’s fabric murals that respond to artworks previously exhibited at OCMA, and which through the course of the exhibit will be turned into clothing that museum visitors may try on, offer art as interactive and accessible.

Lead Pencil Studio, Void Promise: Last Tract A and Void Promise: Last Tract B, installation view, 2017, ©Lead Pencil Studio, photo by Chris Bliss, courtesy of the artists and OCMA

In OCMA Senior Curator Cassandra Coblentz’ exhibition essay, she invites readers to reconsider the permanence ascribed to architecture. Discussing the museum’s original design, location, construction and renovations, she sets the stage to evaluate its suitability. Her writing functions on one level as a meta-narrative of the museum’s own aspirations for growth. Its plan to sell its campus—to a luxury condo developer—in order to relocate, beyond provoking considerations of the museum’s mutability, also invite critique of the implicit link between the museum’s future plans and real estate speculation.

Cesar Cornejo, Raizing, installation view, 2017, ©Cesar Cornejo, courtesy of the artist and OCMA

Cesar Cornejo’s sculptural /architectural model Raizing appears to respond directly to this idea. Built from plywood and acrylic scavenged from museum storage, it could be a model of the site’s future as a luxury high rise. By opening a previously blacked-out window that looks into the gallery, Cornejo literally and figuratively invites transparency. Also in this mix, Cedric Bomford’s sheathed construction scaffold, The Embassy or Under a Flag of Convenience, outside one of the galleries, projects a work-in-progress aura. Though it offers different vantages of the museum as a site, meant to invoke considerations of redevelopment, materially, it’s a let-down, given the range and complexity of projects for which he is known.

The most sobering political note is struck by Ken Ehrlich’s laser-cut archival photographs that document the double history of an American scholar of Persian architecture, Donald Wilber, who was instrumental in organizing the CIA-sponsored coup against Mossadegh.

Santiago Borja, This is Architecture, 2017. Site-specific installation. Cut cement, dirt, woodblocks, and xylographic prints. Dimensions variable (approx. 3 x 6 ft.). Courtesy of the artist and OCMA.

Among the more speculative works in the show, Santiago Borja’s This is Architecture reads as a grave cut into the museum floor. It references a 1910 Adolf Loos text on the symbolic nature of architecture. It also can be read as institutional critique. Ronald Morán’s thread construction and drawings overlaid on photos of modernist architecture (Intangible Dialogues 1-21) throw architecture into the realm of pure thought.

Leyla Cárdenas, OCMA Stratigraphy, 2017. Site-specific intervention. Peeled paint from walls of the museum, steel, dirt from under the museum, marine deposits (Late Pleistocene). Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist, Galeria Casas Riegner, and OCMA.

The museum is even more explicitly the subject in Leyla Cárdenas’ OCMA Stratigraphy, which suggests an incursion of a rammed earth wall into its interior. Built with sediment layers mined from soil underneath the museum dating to the late Pleistocene, it creates an illusion, as if the Earth were subsuming the body of the museum itself. Cárdenas casts the idea of a museum’s permanence—and culture, with it—into the cauldron of geological time.

Imprint, Bryony Roberts’ resin cast of the museum’s corrugated concrete exterior, suggests a death mask. Renee Lotenero’s installation, Stucco vs. Stone, is a riot of photos, depicting portions of buildings, mixed with broken concrete to convey a sense of ruin. Thoughts of ruin take comedic turn with Wang Wei’s Slipping Mural, which imagines the mosaic from the Aldabra Tortoise enclosure of the Beijing zoo sliding off the wall in one piece.

Performance art collective Super Critical Mass (Julian Day and Luke Jaaniste) introduce a light-hearted tactile, audience-activated, sonic installation in Common Ground, where you can kick cups and saucers across the floor and listen to them skitter in the unnatural silence of the museum.