Your cart is currently empty!

Month: January 2016

-

Various Small Fairs – Art Los Angeles Contemporary, 2016

I think we can all agree that there are too many art fairs. We could almost stretch that to say there are too many fairs, period. We generate too many products – most of them of an astonishingly brief life-span, and worth still less of anyone’s attention; and consume far too many of them, wasting an unacceptable amount of time, energy and resources in the process, and generating an unacceptable amount of waste. Art fairs might just be the hallmark of waning western civilization – the sunset of this geologic age as we head into the full-on Anthropocene. We certainly don’t need most of this stuff.

But, as Lear in his pathetic wisdom might put it, ‘reason not the need.’ It’s what we want and richly deserve. The closer you are to the art world, the more intensely you feel it (and, when you get right down to it, the players who are really moving the stuff rarely show up at any fair outside Basel; the artists actually making it will likely skip the openings). We pout and kvetch, complain about the shlep and that we have nothing to wear. And then we go. And it’s Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion all over again. I mean ArtForum. I mean – was that so bad?

It seems almost churlish to complain – especially considering this blog was partially instigated by an art fair. (There were other factors considered – and the instigating fair was not Art Basel, or even Art Basel Miami Beach; but that’s more or less the gist of it.) And there’s always something to see – even if it’s only ‘where they are now,’ as we observe galleries appearing and dropping off the roster of exhibitors, artists moving in new directions and shifting gallery allegiances, or new and old faces in the roundelay of gallery directors and personnel. But it’s not just ‘they’; there’s always someone new; and once in a while, a real discovery. (I first encountered Julian Hoeber’s work at a fair – Blum & Poe made a showcase for him in their fair space – and it was a break-out, revelatory moment. And the beat goes on: Hoeber’s Paris gallery, Praz-Delavallade was represented here, with what appeared to be a showcase of another L.A. artist, Matthew Chambers – less revelatory, but another unpredictable turn for the artist, with what looked like abstracted, appropriated imagery, rendered in something that looked like sprayed felt. (I always wonder how toxic some of these materials are.) I had my eye out for Matthew Brandt; but notwithstanding what was out or what I might have missed, René-Julien Praz (who was there), and his partner, Bruno Delavallade, clearly have an eye for L.A. artists. (They represent, among others, Ry Rocklen, Amanda Ross-Ho,and Jim Shaw and Marnie Weber.)

Obviously what draws us to fairs is a compulsive appetite for the new; and ALAC is no conception; but rediscovering the old – whether as an old forgotten friend or something seen fresh in a radically morphed context can amount to almost the same thing. I didn’t need to look at any Warhols; but I enjoyed coming upon an Alan Saret chartreuse ‘cloud’ floating above the Alden Projects space. My companion for the evening was complaining about seeing “the same old shit,” throughout the spaces, whether local or national and international; but you don’t really go to these things expecting a paradigm shift or to radically reshape one’s entire perspective on contemporary art or the art market.

It’s also great to see some of our local galleries (and it’s hard to reach all of them regularly) shining with their best. I hadn’t been to 1301PE for quite a while (just one of those things…); and their selection reminded me just how essential they are. There was a marvelous Pae White fabric hanging (EVAL 2) glistening with bronze and gold that made me think of a mad collision between the LeBrun/Gobelins tapestries of The Getty’s Woven Gold Louis XIV-era exhibition and Mies van der Rohe. Ana Prvacki’s Music Stand was silent but wickedly expressive – genius. Speaking of fabric, Channing Hansen showed a more structured knit ‘painting’ (in black-and-white) at Marc Selwyn. And am I just regressing into a moment of Paco Rabanne nostalgia, or was I alone in developing a crush on the Rosha Yaghmai hanging of tinted eyeglass lenses and an electric storm resin-fiberglass unfurled ‘awning’ exhibited at Kayne Griffin Corcoran. I’m mad for the merest suggestion of windswept winter and waterscapes; and, alongside some classic John Divola photographs, Gallery Luisotti showed an amazing multi-processed multiple-exposure inkjet print by a CJ Heyliger – a real discovery. Julia Haft Candell showed some cunning ceramic work at The Pit, an off-the-beaten track gallery in Glendale – which was a discovery in itself.

It’s also wonderful to see work from the art world well off the ‘beaten path’ in the global sense. I’m talking about the Southern Hemisphere. Obviously there’s a lot of art coming out of Sydney, Melbourne and Victoria – but how much of it do we actually get to see outside of London and New York (at, uh, fairs)? Probably my own damned fault for being so obsessed with the Australian Open and the survival of the Great Barrier Reef. But the Sutton Gallery showed some brilliant work in clay by Matt Hinkley and some Jet Stream visionary graphic and mixed media sculptural work by another artist I’d never heard of – George Egerton-Warburton. You could hear the wind whistling through the eucalyptus stands – and I drifted out to the night with that wind in my ears. Or was it the smoke machines in front of the entrance? We have a couple more days to figure it out.

-

The Man Who Fell to Earth (Part 3 of 3)

“We like dancing and we look divine.”

David Bowie, “Rebel Rebel”

from Diamond Dogs, 1974

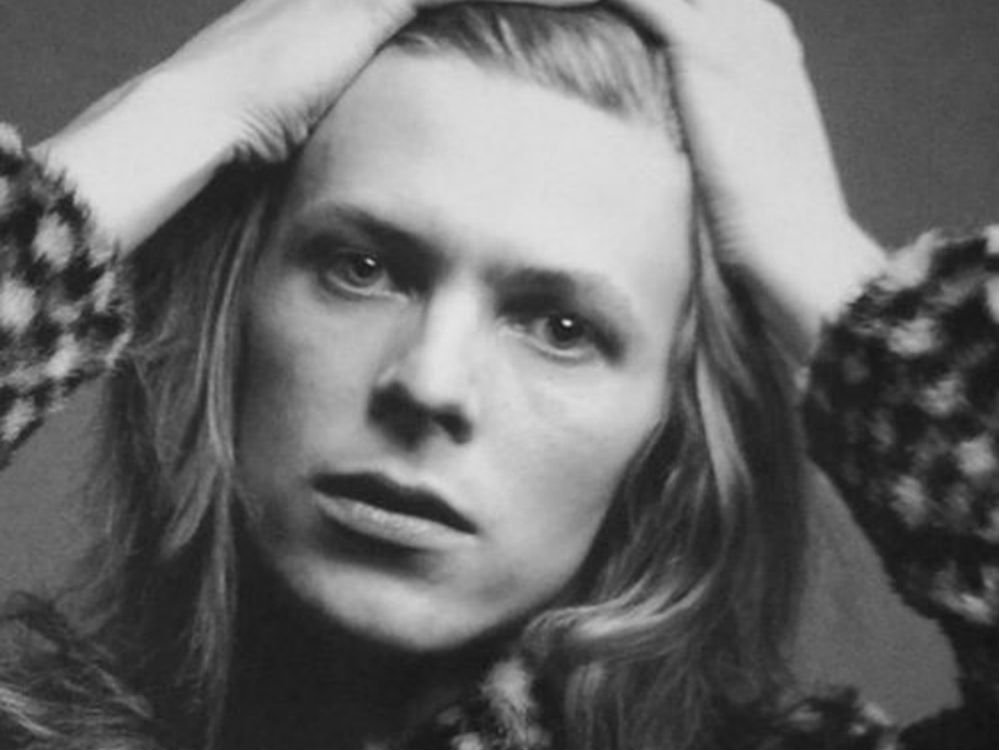

Finally – Bowie. Forever Bowie. “Peace, peace! he is not dead, he doth not sleep….” I want to quote Mick Jagger (to be very specific about it) quoting Shelley (from Adonais – Shelley’s own elegy to Keats) – as he did (in exactly this stanza) in a 1969 Rolling Stones concert at Hyde Park only days after the death of erstwhile bandmate (but really part of its soul), Brian Jones. After all the tributes, eulogies, remembrances, anecdotes, what is left to say?

As the shock was just setting in (and this was before I’d even given in to my beast of a cold and gone to bed in a big way), I was thinking about how well the amazing Victoria and Albert Museum show, David Bowie Is, had summed up Bowie’s influence across the full spectrum of art and culture. He simply is – no receding into a past tense for him – and is so many different things, impossible to pin down in any definitive way – musically, theatrically, artistically, culturally, politically, sexually, sartorially, stylistically.

It was a comfort that the local public and college radio stations were playing Bowie constantly through the week, as I shivered in my sickbed – sparing me any need to hunt for my Bowie CDs (which now seemed sparse – given that I’d sold or given away my vinyl copies of Young Americans, Station to Station, Low, Heroes and Lodger). All those lyrics tailor-made for feverish chill moments: “Look out you rock ‘n’ rollers … pretty soon now, you’re gonna grow older.” “Do you remember the bills you have to pay … for even yesterday?”

I remember hearing “Space Oddity” for the first time and exactly where I was when I heard it (a junior-wear department in a Bullock’s department store in 1969) – though I would have no idea who was actually singing it until almost three full years later. That voice – with its distinctive wobble and catch and the barest hint of glossed-over east London – was easily recognizable as the same voice singing “The Man Who Sold the World” and “Changes,” which was already becoming something of an anthem. It was only then that I acquired my first Bowie album, Hunky Dory. Dylan (and Warhol) were already icons – and the hard blues Brit-rock that was an early music touchstone had reached a kind of climax in that year and begun to explode in new directions. The most interesting pop music was diversifying and critically evolving. We’d already seen movement in these directions on our own shores – by way of the Velvet Underground (no small coincidence that Lou Reed’s first solo outing, Transformer, was produced by Bowie and Mick Ronson), various folk-influenced rockers, and a smattering of L.A. and California bands. In the meantime (inspired by Rolling Stone?), Warhol had himself launched Interview. The worlds of pop, art music, movies and fashion were beginning to converge. In other words, I was just catching up. And then Ziggy Stardust landed in America. The rest, as they say, is the history of the world long after we’ve left the planet.

It’s been interesting to observe the enormous response we’ve seen in the art world – certainly here in Los Angeles. Off the top of my head I can’t think of any fine artists acknowledging his influence on their work – it’s funny how a resistance to acknowledging a pop/mass cultural influence persists among so many avant-garde artists even as the divide between pop/mass and high art domains has blurred if not dissolved altogether; yet the influence, however subtle or indirect, is there. (The distrust was, of course – as Bowie himself would have pointed out – mutual.) The response to his passing from the world of fashion and design was, as expected, almost universal. Bowie’s influence on the fashion world was immediate (consider my own first encounter) and more or less continuous over more than four decades. (Jean-Paul Gaultier reached back to Bowie’s Ziggy incarnation in a collection only a couple of years ago.) But Bowie’s influence on fashion was merely the by-product of a project that was much larger and more personal. Fashion ‘got’ him first (alongside music) because fashion went global long before the art world. (It also had something to do with what was happening in both art and fashion, as well as music, in London in the 1960s.) But Bowie was never a creature of fashion (though he understood its uses) or even, notwithstanding his beauty and innate elegance, a style icon in the conventional sense.

“Elegance is refusal,” Diana Vreeland once famously said – and Bowie was certainly about that. He refused to be boxed in – to be classed (up or down), classified or categorized – musically, artistically, theatrically, sexually, politically. He was a product of his time without being constrained by it. The glitter- and glam-rock of the early 1970s was simply a logical outgrowth of something that had been going on since David Jones left art school (he also studied dance and theatre – and no small coincidence that so many rockers of that period emerged from the same art schools). That time – the late 1960s and early 1970s – was a time of pose and performance, which is not to say it was merely about artifice or fashion silhouette. It was about a more fundamental shift in consciousness and attitudes. Technology and the sexual revolution naturally played into this shift. Bowie said once in an interview (with Terry Gross on her WHYY program, Fresh Air) that his original notion was to write musicals in a rock idiom – and it sort of makes sense. He’d come out of all of that – art school, dance, the music hall and theatrical pantos, alongside jazz and rock‘n’roll. But he would have to come up with something new: Sandy Wilson had already written The Boy Friend (and Ken Russell made the film – as he would later make a film of The Who’s rock/concept musical Tommy). Besides Ken Russell, there was Nicolas Roeg, who, with Donald Cammell, had turned an entire film around motives of pose, posture (and imposture), and performance – and a vehicle for Mick Jagger – Performance. (Not so coincidentally, the dress Bowie wears on the cover of The Man Who Sold the World was designed by the same Savile Row hipster who had designed the white tunic-dress Jagger wore to that aforementioned Hyde Park concert in 1969 – Michael – sometimes known simply as “Mr.” Fish.) His approach was really something adapted from art school – cross-media and cross-disciplinary, a kind of musical bricolage (albeit with polished production values). It could be raw or minimal, futuristic or simply atmospheric, theatrical or simply danceable. Bowie embraced and embodied the blur.

He also embraced an art of contingency and collaboration. One musical identity – even his own permutations – wasn’t enough for him; hence his collaborations: with Mick Ronson, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, Freddie Mercury, Trent Reznor; and on and on. Aside from Iggy and Ronson, if there was a musical contemporary who resembled him, it might have been – for all their differences in styles and sensibility – Frank Zappa, another musician who could never be boxed in.

Which is why the man who played The Man Who Fell to Earth and left the planet (in such ironically timely fashion) as it began its transition to a place not unlike the doomed planet in that film, is and will be probably up to the day we’re finally compelled to leave it.

-

“Some Make You Sing….” (Part 2 of 3)

Something kind of hit me today

I looked at you and wondered if you saw things my way

. . .

We’re taking it hard all the time

Why don’t we pass it by?

David Bowie, “We Are the Dead”

from Diamond Dogs, 1974

The first part of this post promised a superfecta; and I’m not sure it’s possible to live up to that, if for no other reason than simply the difficulty of making any kind of conclusive judgment on the kinds of shows I’m looking at in the space of a few hours spread out over 30 square miles. Sure, there are a few (e.g., the shows already covered in the first part of this post) – and even there, it would be absurd to say that my opinion might not be revised over repeated viewings. This is why we revisit shows in the first place. Or why we return frequently to favorite works in museums. Our first impressions are never our last; we bring something fresh to each viewing and take away something new.

Which is why I’ll be going back – not just to the shows I’m about to mention, but to the shows covered in (and some of those omitted from) the last post. I wanted to linger at George Legrady’s show at Edward Cella; and certainly his multi-layered, multi-faceted lenticular panels invited it; but couldn’t have spent more than 15 minutes with them. Memory is mined and manipulated in Legrady’s work, no less than Barnette’s, and far more explicitly. It also moves in both actual and remembered space and time for both the viewer and (presumably) the artist himself – which apparently related directly to the two-channel interactive animation piece Legrady is fascinated by the collage/montage of time and memory; the contemporary (or simply invented) foreground and (remembered or recovered) background of memory. The groundwork for the work was apparently laid with the discovery of a collection of family photographs taken mostly in eastern Europe (between Hungary, Romania and Transylvnia); and the lenticular work here apparently draws from photos of a Transylvanian picnic outing. You can see immediately how the lenticular work might lead to animation studies. The lenticular prints have their own quality of animation (albeit partially supplied by the viewer), but more important is the inherent fascination of the underlying photographic material and the overlaid imagery. I had to wonder how the animation would amplify that experience.

As I occasionally do in these instances, I had a look at the press release which set out Legrady’s aims more or less straightforwardly; also noting his “contributions to the computational arts,” which sounded like something more applicable to tax accounting – but maybe there’s a layer I’m missing.

It made for a striking transition to go from Chris Ballantyne’s show at Zevitas Marcus (next door to Edward Cella) that pursued a number of architectural and geometric themes and motives (and natural, too) to Toba Khedoori, whose past work has exploited both architectural and natural motives in her draughtsman-like explorations of existential and quasi-serialist geometries, at Regen Projects. Settting aside one striped painting that seemed almost literally a serialist work, it was quite different from what I expected. Here, only two paintings – seemingly tilted, eliding views of polished ceramic tiling more or less filling their respective canvases, one presented more frontally than its angled mate, bore distinct relation to that past work. Here, even meticulously rendered branches and leaves (in a completely white space) seemed well removed and on another plane completely from even previous naturalistic studies. Rather, the emphasis seemed to be a Fontana-esque contrast between the delineated plane and the absolute void – physicality and nullity.

From this kind of ‘naturalistic’ yet slightly ethereal art concrète, it was not much of a leap to the equally ethereal yet silken domain of Lita Albuquerque, at the Kohn Gallery. Albuquerque is well known for (frequently site-specific) work that bears on the body’s relationship to both the earth and cosmos; and surrounded by gold and silver discs in the main gallery, each inset within dense fields of rich, vibratile color that evoked both terrestrial and celestial qualities – purples both boreal and nebular, luminous sapphire blues that were both atmospheric and referenced the cosmic infinitude – the viewer felt suspended in a lunar ceremony. The jewel-like intensity of the color owes something to Japanese Enogu technique (or so the press release informed us – with the colors laid over layers of black and white); which may have something to do with the ceremonial aspect of the show. It was impossible not to be reminded of Japanese screen and silk painting.

: : :

That little ellipsis marks the approximate moment I broke off to surrender to the viral mischief that had besieged me. Part 1 went up without too many digital hitches – along with a nod to Bowie, whose funeral pall I was involuntarily sharing in body as well as spirit, as I succumbed to what felt like a not-so-mild bout of bubonic plague. That week-end was as notable sonically as it was visually; though, as with the George Legrady lenticulars, everything seemed strewn beneath leaves, branches, lakes and forest thickets. Even before the evening’s openings, I had the great fortune of hearing most of the Met broadcast of the closing performance of this season’s (David McVicar) production of Donizetti’s Anna Bolena – and possibly one of the greatest performances of the title role I’ve ever heard. In Sondra Radvanovsky’s performance, the dazzling vocal pyrotechnics (the role has an intimidating range from lowest to highest register) were matched by an incomparably supple and dramatically insightful handling of the role’s emotional complexity. Donizetti’s Bolena is every inch the queen she actually was, but also vulnerable and manifestly conflicted. Radvanovsky gave full scope to that emotional breadth and conflict in a dazzling coloratura performance that seemed to move inexorably from a high-strung regal poise to passion and indignation, from romance and resignation to tragic elegy – eclipsing possibly every other performance I’ve heard in the role, including Beverly Sills. She was well paired with her various foes and foils, including the incomparable Jamie Barton in the role of Giovanna (Jane Seymour), Ildar Abdrazakov as Enrico (Henry VIII) and Stephen Costello. There were so many great moments, I couldn’t begin to enumerate them all; but I will say Radvanovsky’s aria at the close of the first act (paralleling Abdrazakov’s responsive aria) was ineffably heart-rending.

I guess some people would say I was ready to get carried away on the first horse I mounted. But there’s really nothing quite as moving as the human voice. The following day, Emmanuel Ax brought an equally, agelessly supple technique back to Disney Hall for a performance of the Franck Symphonic Variations with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. (The Chopin C# minor nocturne he encored with wasn’t bad either.) The Pierre Boulez Mémoriale for flute and octet had actually been my selected ‘A’ side for the afternoon. Its timing – only days after Boulez’s death at 90 in Baden-Baden – was purely coincidental; but its original spirit made an appropriate memorial to its composer – and the soloist, Denis Bouriakov, and guest conductor Daniel Harding captured that spirit beautifully. Another uncanny coincidence was Harding’s expressive and slightly ‘contrapuntal’ conducting style – strikingly reminiscent of Boulez’s own distinctive ‘contrapuntal’ conducting style, though, unlike Boulez, Harding used a baton through all but the Mémoriale. Hard to say what Boulez would have made of the unbridled lyric romanticism of Schumann’s 2nd C major Symphony; but Harding and the Phil made something gorgeously soaring of it. The third movement C minor Adagio was possibly the most beautiful rendition of that movement I’ve ever heard.

Finally – Bowie…. [Continued Part 3]

-

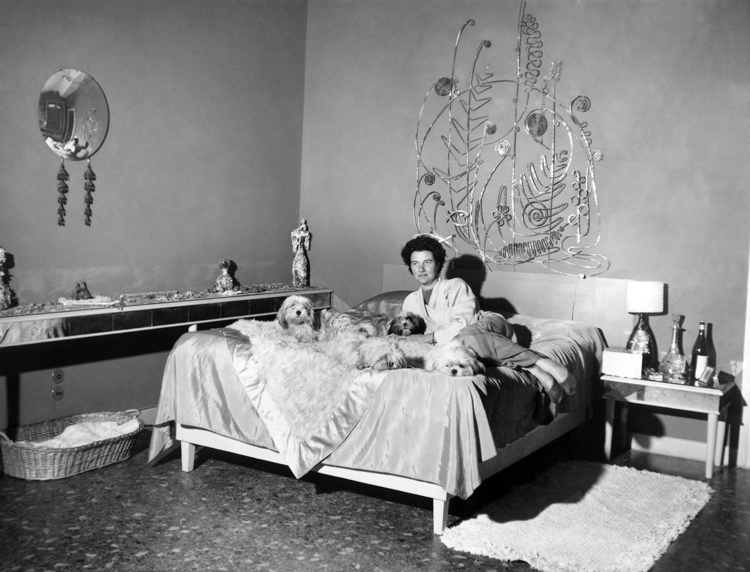

Chris Kraus Papers Acquired by NYU

New York University’s Fales Library & Special Collections has acquired the papers of writer and filmmaker Chris Kraus, who rose to fame for “I Love Dick” (1997) and “Aliens & Anorexia” (2000), among other written works combining autobiography, theory, and fiction. The acquired materials include her personal diaries, notes, films, videos, and correspondences.