Your cart is currently empty!

Month: November 2008

-

Art Ceases to Desist

With today’s digital era so rich in explicit displays of virtually every aspect of the human experience — including amateur exhibitions of bodily functions beamed to us live via webcam — the idea of museum exhibits raising hell in America may seem, well, passé?

But a generation ago a handful of works by artists Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano ignited a national pissing match (if you will) over art, its public funding and, ostensibly, freedom of speech.

Of course, the volume of societal dialog on public art exhibitions and taxpayers’ financing controversial works had been escalating long before the visions of Mapplethorpe and Serrano were hung on the proverbial gallery wall, but it was those two artists who were at Ground Zero when simmering cultural tensions exploded into a volatile debate.

Looking at it now, Serrano’s 1987 Piss Christ seems an odd selection for what was then denounced as the apex of petty vulgarity fraudulently pawned off as “art” by a bored bourgeoisie looking for a cheap thrill on the taxpayer’s tab. The photograph delivers its punch not through the sublimely beautiful image of a radiant crucifix bathed in warm hues of amber, but rather lands a haymaker through the title of the work itself—and what it reveals.

Those two words — Piss Christ — turned a richly divine image into something the mob saw as starkly demonic. Yet reverse the words and televangelists would be selling it.

But it wasn’t until two years later, in May of 1989, that Serrano’s urine really hit the fan. Seizing on the fact that the National Endowment for the Arts had indirectly awarded Serrano a $15,000 grant, New York Senator Alfonse D’Amato saw a golden (so to speak) opportunity to grandstand on publicly funded “filth” and took to the Senate floor to tear up Piss Christ both figuratively and literally. D’Amato’s esteemed colleague from North Carolina, Sen. Jesse Helms (think Strother Martin’s character in Cool Hand Luke), who had been agitating for a brawl with the NEA and its damn Yankee liberal supporters, jumped in with his buddy Al.

“The Senator from New York is absolutely correct in his indignation and in his description of the blasphemy of the so-called artwork,” Helms said. “I do not know Mr. Andres Serrano, and I hope I never meet him. Because he is not an artist, he is a jerk.”

Helms’ view of Mapplethorpe was decidedly more ominous both in tone and implication, with the astute senator alerting the New York Times that the artist was “an acknowledged homosexual.” If Serrano’s work rocked conventional perceptions of the Judeo-Christian boat, Helms undoubtedly saw Mapplethorpe’s unconventional perspective on bullwhips and black men as the wall hangings from the seventh ring of hell.

And Jesse wasn’t alone. Mapplethorpe’s work resulted in protests and criminal busts in Cincinnati, where city fathers charged the Contemporary Art Center and its director, Dennis Barrie, with obscenity and a jury of mid-Westerners delivered an acquittal.

Those were some big headlines two decades ago. But if the argument has faded, its legacy has not. “The culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s changed the very structure of arts funding in ways that now often go unremarked or unnoticed,” says Richard Meyer, an associate professor of art history at USC who has written extensively on the subject. “Individual artists are no longer eligible, for example, for funding from the NEA and virtually no one expects—or applies to—the federal government to support dissident, controversial or otherwise oppositional art.” Meyer says the result has been a withering away of the “artistic culture of social dissent,” erosion he calls “a genuine loss and a great shame.”

Perhaps. But in hindsight it’s hard to shake a sense of uniquely American frivolity that surrounded some of the proceedings, indulging our super-sized taste with an over-dramatized battle between freedom and censorship.

The fact is that even angry grandstanders like Helms and D’Amato publicly acknowledged the fundamental right of Serrano and Mapplethorpe to make and display their art. Consider that in comparison to the artists in the Netherlands today, who need round-the-clock protection (provided by the government) for having dared to offend Islamic sensibilities. The very credible threats against these artists’ lives today puts the rants of the Jesse & Al Show, and even the lame busts, in stark perspective.

And Serrano’s back with a new show—entitled simply Shit and featuring yet more of the artist’s, um, excretions—that opened at the Yvon Lambert Gallery in Chelsea in September. As Artillery went to press, there’s no word yet of any senators denouncing him from that chamber.

But I suspect if the exhibit’s patrons listen carefully as they line up to appreciate the oversize photographic servings of feces, they may well hear the chuckling drawl of the ghost of a good ol’ boy reminding them, “You get what you pay for.”

That goes for the government as well as the art. ■

-

Kerry James Marshall

This article originally appeared in our November/December 2008 issue on Everyday Politics:

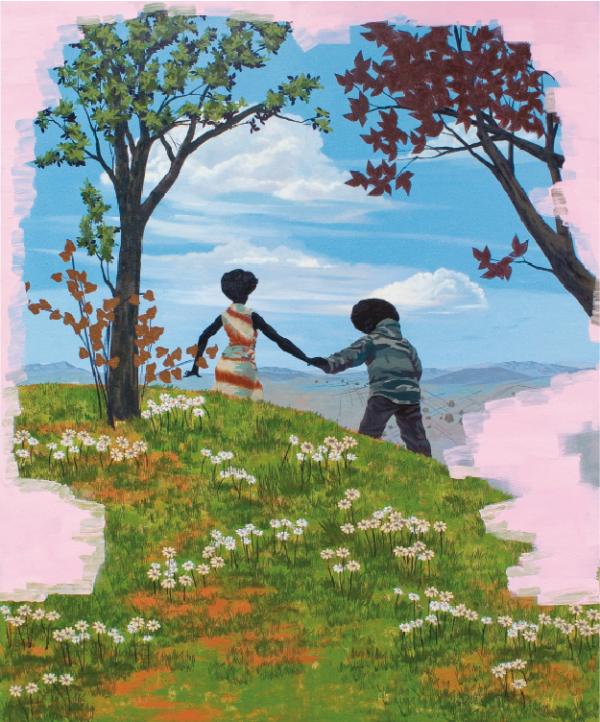

Nov/Dec 2008 Artillery cover. In a text written for this show and displayed on one of the gallery walls, Kerry James Marshall says “I am working on paintings that address the theme of LOVE.” “Love” is less a theme than a pretext for Marshall’s real subject, which is history. There is nothing of the “idyll” in any of these paintings — and “wistful” is not a word that can be easily attached to their calculated bits of romantic fancy. At the risk of sounding either latently racist or completely loony, as I was looking at the paintings, a line from an old Sondheim show tune ran through my head: “Liaisons – what’s happened to them?”

Like the undercurrent of disillusionment and desperation that runs just beneath the flirtation and frolic of the Bergman/Sondheim vehicle, there is a kind of sadness and not a little anger beneath these “Rococo” motives (e.g., a woman’s body sinuously stretched out in the grass of a clearing — singly or in a couple; a couple hiking or chasing over a dune or hilltop) that, today, are a stock of kitsch imagery. Marshall alludes to the kitsch in the more schematic passages of his “pastoral” settings (fields and bluffs of grasses and wildflowers). Marshall conveys a kind of impatience through abstraction — or obliteration — for his own apparent pseudo-nostalgia. The landscapes aren’t lost in the miasma of gossamer fabrics and the rosy filtered light of wooded parkland or sunsets, but deliberately whittled away at the edges, brushed out in broad, flat pink strokes. This is about historical revisionism and displacement; also, simply power.

Africans or (African-French) don’t begin to appear in French painting until approximately the early 19th century. They appear somewhat earlier in Italian and Spanish painting in the late Renaissance. So what? How many Africans were there in France at the time? And just how many Africans made it to the European royal courts — where these paintings took their inspiration — anyway? Inspiration might be overstating it. The kind of pastoral fantasy worked by Fragonard, Watteau and Boucher was exactly that. It was sheerly escapist fare even for the aristocracy for whom it was intended. The vast majority of white provincial French people were similarly closed off from this world.

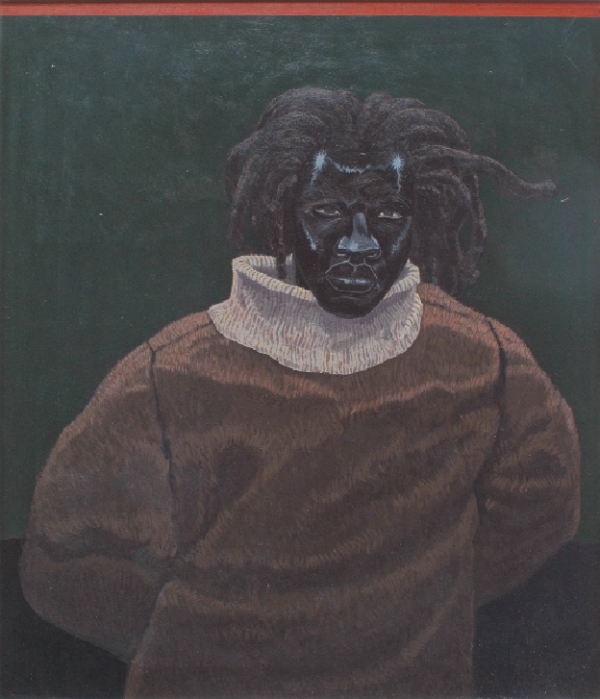

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of John Punch (Angry Black May 1646), 2008. Even before we view Marshall’s “love” pastorales, though, we have a sense of this confrontation with Eurocentric ideals of beauty or nobility in a series of portraits hanging in the front gallery. They’re formal portraits of beautiful people. One, a proud, somber, distinctly African and very black face sporting a thick mane of dreads, in a sable-colored sweater has a lion’s bearing that has nothing to do with the over-sized cowl neck of his sweater. African or not, this could be the mien of an Elizabethan lord — or conceivably an urban intellectual from anywhere.

Directly across from this portrait is another, somewhat angrier, lordly black man, this one swagged in gold chains — much as he would have been had he been painted by, say, Titian. Titian never painted a black aristocrat, but he might have if there were any to be found in Venice.

Marshall is doing more here than simply confronting European notions and traditions, though. He’s claiming them for his own — which, as for any late 20th- to 21st-century American artist, they are. But is there really a point to photoshopping (in painterly fashion) black people in or “pink-washing” the fantasy out? It’s as if Marshall wants a rewrite of art history. Africans are noticeably absent from European painting until well into the 19th century — an implacable historical fact that is pointless to argue with.

Marshall’s portraits are undeniably beautiful; but the most interesting work here by far are the comic panels in the last gallery from Marshall’s “RHYTHM MASTR” series — a very contemporary order of cultural and historical confrontation — where past and present collide in the kind of gritty, multi-cultural, polyglot urban tide pools ubiquitous in cities like Los Angeles. In one panel, a voodoo idol or ceremonial figure is seemingly conjured by a contemporary figure in the foreground with a bongo drum. In another, titled Ho’s Stroll, the sense of anywhere/everywhere is explicit: “What is this place?” A cloud of Asian characters issue from a van, while the protagonist takes on the 20th century: “If Lincoln supposta freed our asses in 1865, why the fuck was we gittin our heads cracked tryin to vote, in 1965?” This is where it gets interesting: at the divide (or not) between cultural and political disenfranchisement. Why do I have the feeling we’ll be asking similar questions this year in states like Ohio and Florida?

Kerry James Marshall: PORTRAITS, PIN-UPS And Wistful Romantic Idylls, Exhibition Dates: September 6- October 24, 2008, at Koplin Del Rio, Culver City, CA. Images courtesy Koplin Del Rio Gallery, Culver Ctiy, CA

-

First Lady Love

It all started with a dream. “I was in a small library, and she opened the door. She put her file folders down and pinned me to the wall, kissing me,” recalls painter Sarah Ferguson. “She was so, so forthright. I found it very refreshing.”

The woman in the dream was Hillary Clinton. From that day in 2007 forward, the former presidential candidate has been the primary focus of Ferguson’s work. In addition to oil portraits, Ferguson has also created numerous photo collages, some of which can be seen on her website and in a self-published book, Hillary and I. Her obsession with the politician seems one part feminist, three parts erotic.

“Hillary is portrayed in the media as cold and calculated, but I see her as sexual,” states Ferguson unequivocally, and she’s on a mission to get others to recognize Hillary’s sensuous side. “When I read Maureen Dowd, the Hillary she concocted in her head was so different than the one in my head. In a 100 years, people might look back at Dowd’s writing and form an idea of what Hillary was like. With these paintings, I’m trying to document my viewpoint.”

In Ferguson’s East Village studio, Hillarys abound. There’s a close-up of a pissed-off looking Hillary titled “Pink Hillary,” the first of the series. “I love the expression. Those eyes! She’s so sensitive, so prickly!” Ferguson coos. A portrait of Hillary pondering a lizard shows the viewer a softer, more private side of the public figure. Yet another canvas places Ferguson in the foreground, sitting in a chair with a microphone between her legs, while Hill looks on from the background, microphone held horizontally in both hands. Ferguson painted that one shortly after the Democratic Convention. “I’m holding the microphone in my lap, away from my mouth, because my voice has been denied.”

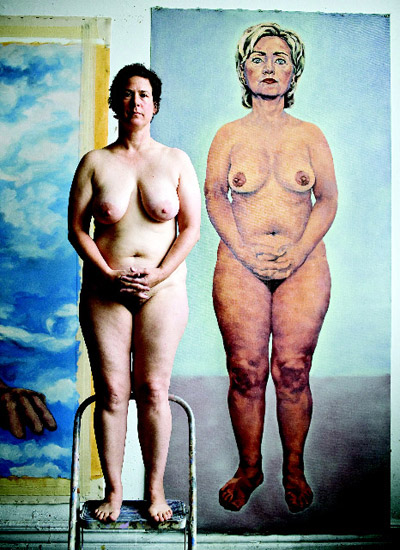

Among these many moods of Hillary, an eight-foot-tall portrait stands out. Hillary’s face is molded in a familiar expression — lips tight, chin slightly raised, her demeanor serious and authoritative. To her detractors, this “don’t fuck with me, fellas” look might epitomize what they dislike about her. The twist here is she’s buck naked, staring you down as if to say, “What are you looking at?” Her aging flesh and sagging breasts are painted in loving detail. “I could have made her more erotic, but this is the beauty of the real. There’s no artifice. She’s stripped bare,” Ferguson explains.

Photo by Rainer Hosch On Christmas Day 2007, she posted an image of Naked Hillary on Flickr.com. “I was so involved in political blogging, and I wanted to talk about things that weren’t being discussed, like the sexism [that Hillary provoked]. Within a week, I had 500 hits.” Things continued at that pace until Flickr tagged the image at the end of February. But Ferguson was happy with the results of her experiment. “The only way to find it was by typing ‘hillary naked’ in the search, so at that moment, there were a lot of people who wanted to see Hillary naked! I really tapped into something.”

Until about six years ago, Ferguson, 43, was pursuing a career as a math professor. But shortly after she was awarded tenure at Wayne State University in Detroit, Ferguson asked for a leave of absence and moved to New York in 2002 to paint full time. She enrolled in an MFA program at the School of Visual Arts in 2006, and graduated this past spring. “Both math and painting are a search for truth, and both are a battle. I would end up with a big pile of scratch paper, trying to figure out a formula, and I must have painted over Naked Hillary five times, trying to get it right.”

Interestingly, Ferguson had one of her biggest breakthroughs working on a 7′ x 8′ canvas entitled Hardball, that depicts Chris Matthews and Keith Olbermann jerking each other off. “Since I don’t care about them like I do Hillary, I was free to make mistakes.” The violet blue tones of the canvas make it clear that the couple is watching television. “Porn?” I ask. “No, they’re watching Hillary!” Ferguson replies. Silly me.

With Hillary’s bid fading into history, Ferguson intends to continue painting her muse. In her most recent work, Ferguson put Hillary’s head on a doll’s body. “It’s a little surreal. There’s some detachment. It’s less personal. A dealer who looked at my previous work said most artists don’t work from complete identification. But I had to go through that living with her, talking to her, having her as an imaginary friend.” Ferguson sees this new Hillary as a universal mother to us all. “She’s looking down and her head is like the size of your mother’s head when you were getting your ass wiped. It’s like she is there to take care and provide and clean things up. And the heavens are there, and the sky. It’s death and rebirth. I think her role as senator will be much larger now,” says Ferguson, with a hopeful, lusty glint in her eye. ■