Your cart is currently empty!

Ken Gonzales-Day

The singularly remarkable thing about Ken Gonzales-Day’s re-creation of his breakthrough 1993-96 photographic project, “Bone-Grass Boy: The Secret Banks of the Conejos River,” is the infinitely expansive temporal envelope it seems to occupy. This is more than partially by design in that it appropriates literary tropes and motives of 19th century frontier novels to serve a much larger conceptual and cultural conversation. That such a conversation might be no less relevant and possibly even more urgent today, though, could scarcely have been anticipated when the work was being made. Now, against a backdrop of seismic human migration and planetary change, it seems as if the project could have been made 60 years ago or just yesterday.

Conceivably at the time it was made, the work addressed notions of cultural narrative and cultural/social identity, and the oppressiveness of historically predetermined norms and institutionalized ignorance. Today the conversation seems much broader and more fundamental—and the gallery’s installation reinforces this sense. The first gallery is styled as a kind of drawing room, the photographs hung in a gracefully uncluttered salon-style grouping. Selected portraits are set off by themselves, as if they were family and ancestral portraits. Half of these are against walls painted French blue, the others against a faux wallpaper-style mural-map of historic and cultural landmarks of the Conejos River/Rio Grande/Four Corners basin that extends across the Southwest—a region where Meso-American and North American indigenous peoples once crossed and commingled and variously repelled, endured or were nearly exterminated by invading European armies, only to contend finally with the Anglo-American dominant forces of the United States government, whose rapacious appetite for the land’s resources can never be satiated.

The installation also plays out notions of domestication and historicization through the souvenirs, escutcheons and personal memorials that trace a genealogy or ancestral history, all helping to frame the fragmentary personal creation myth so many of us take away from our childhoods—our first, albeit usually inchoate, sense of identity and origin. Gonzales-Day underscores a quality that is rarely acknowledged by subject or image-maker—a composure in which the subject is usually partially complicit. ‘Remember me/this,’ the poser silently implores. Suppressed to one degree or another is the more complicated actuality from which such moments are fabricated. The traces that survive are intriguing and delightful, e.g., an ostensibly ancestral señorita, whose dance, in a busy 18th or 19th century village market fiesta (Untitled, #36, 1996), is clearly hers alone, with only a few musicians paying her much attention.

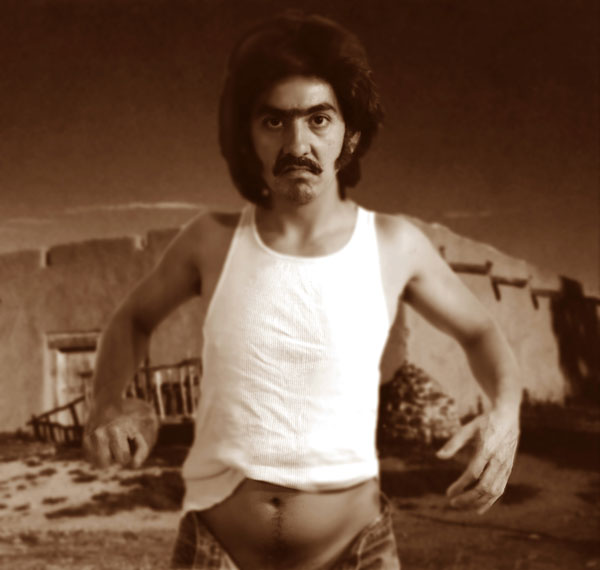

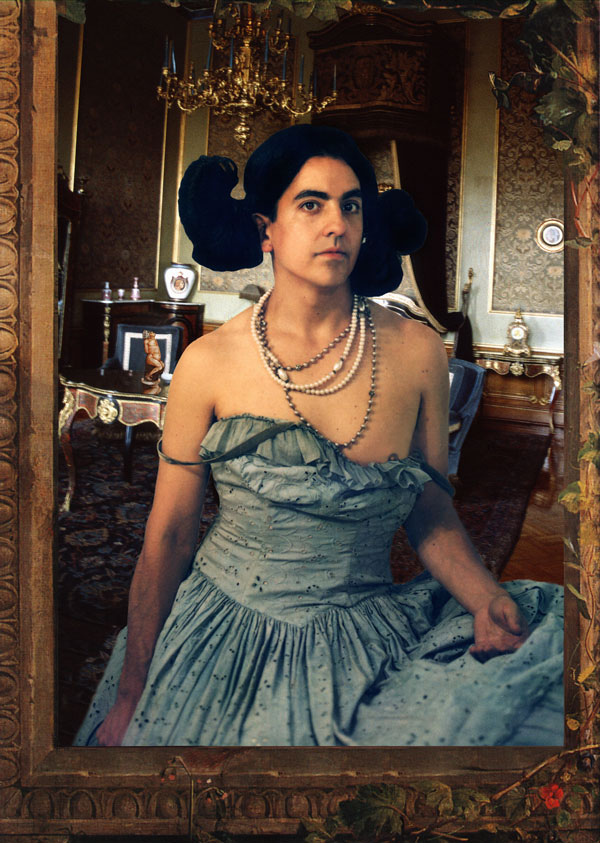

Gonzales-Day both acknowledges that suppression and carries it forward to the surface/present by inserting his own image, variously posed and costumed, into these settings, both staged and culled from historical artifacts and memorabilia. All the characters depicted are embodied by the artist himself, from the progenitor “bone-grass boy”—a bather along the lines of a proto-symbolist Cezanne or Picasso (Untitled, #13, 1994), to his brother, sister or lover (Untitled, #28 and #14, both 1996), to the face of the ancestral señorita from #36, to the portrait of an aristocratic doña who might never have left Spain (Untitled, #5, 1996).

At some point, Gonzales-Day made a decision to extend the narrative to reflect something of the colonial drama that propelled such ancestors across an entire region of the American Southwest to include images of the conflict and actual violence that played out in this migration. A second gallery presents Gonzales-Day’s frequently guignol re-enactments—from Cain-Abel fratricide to a sword-wielding don, and mob-style executions. He goes still further with his embodiment of these characters by giving them names (‘Nepomuceno’ and ‘Ramoncita’) and memorializing their fictional anecdotes: Ramoncita Gonzales’ memoir, The Bone-Grass Boy: The Secret Banks of the Conejos River, bears the Charles Scribner’s Sons imprint with a publication date of “1892.” He incorporates the gender blur of the series by introducing the concept (naturally in the “Foreword” written by Ken Gonzales-Day himself) of the berdache, or (as Gonzales-Day defines it) “two-spirit person.” A selection of the pages of this “found memoir,” which Gonzales-Day characterizes as a “never-made,” are displayed in deliberate proximity to the images of theatricalized violence.

At the center of the gallery is a severed head—a gory theatrical prop, with faux blood and vasculature. It’s almost a reversal of Gonzales-Day’s “Erased Lynchings” series from the early 2000s—as if the flatness of the photography, with Ramoncita’s cartoon-squiggle Empire-style helmet hair and the ancient doña and Nepomuceno’s frontier daguerrotype-portrait demanded a three-dimensional response. It doesn’t—but given the character of the present moment, we can understand why it might not be entirely unexpected.