New Zealand based digital artist Gregory Bennett is a virtuoso when it comes to utilizing high-end 3D animation software and motion capture to create animated videos in which featureless android bodies inhabit synthetic worlds, wherein they are trapped in perpetual loops. As the camera’s point of view pivots (here, it is the all-seeing eye), robotic bodies frolic, perform calisthenics and march in place as if on a never ending conveyor belt traversing a geometric metropolis.

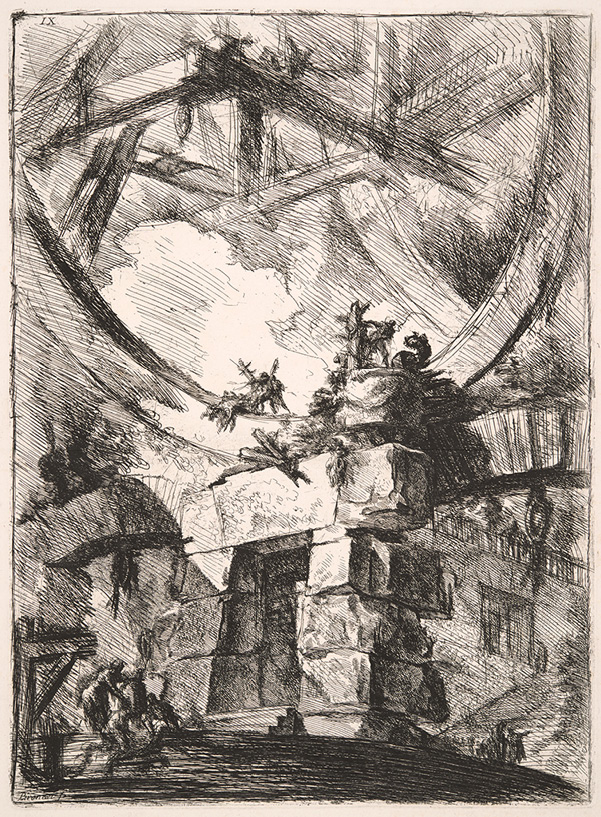

The ingenious pairing of Bennett’s three animated videos Panopticon I (2015), Torsade III (2017) and Exosphere (2018), with Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s etchings from Imaginary Prisons (ca. 1740s) calls attention to the similarities and differences in the creation of these fantastic spaces. While Bennett’s works maximize what can be done with digital technology, Piranesi’s cross-hatched lines, vertiginous compositions and exacting geometry also pushed the boundaries of what was possible in his time. His etchings detail labyrinthine architectural spaces that are darkly mysterious and seemingly endless. His works depict church-like architectural spaces that function as prisons where anonymous figures (as silhouettes and shadows) are hidden within the darkness. Piranesi’s prison spaces are confined, yet suggest infinite expanses from which there is no escape.

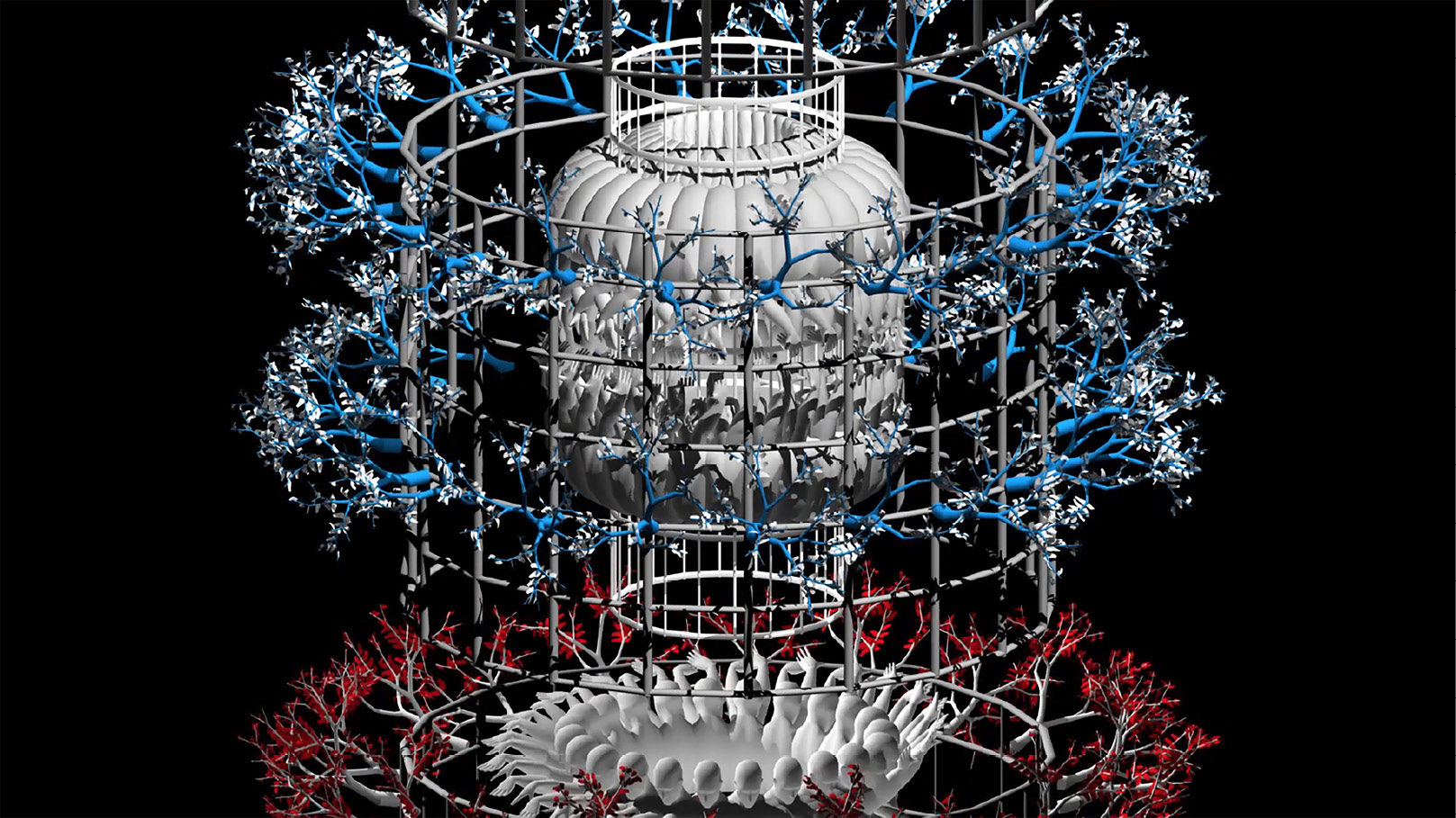

A similar atmosphere pervades Bennett’s work. His software-modeled robotic figures go about their routines, moving through geometric landscapes like soldiers in formation. Occasionally some group together to become mechanized structures or flowers dancing in unison like synchronized swimmers. Their world is utopian and dystopian simultaneously. In Bennett’s 8-minute Torsade III, the figures are trapped in ever-morphing circular cages that spiral from the top to the bottom of the screen. It is unclear, however, whether they are being held against their will. The pulsating electronic soundtrack reinforces this ambiguity. Although the juxtaposition with Piranesi is apt, Bennett’s animations also share a kinship with the works of M. C. Escher whose impossible, labyrinthine structures also explored the idea of infinite spaces.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Giant Wheel, (Designed 1749 – 50, Printed 1835 – 39), courtesy of AA|LA.

The digital environments of Bennett’s animations echo Piranesi’s and Escher’s worlds, where stairways lead nowhere or abruptly end. Yet, in Bennett’s renderings, the figures, plants and machines are often depicted in shades of red, yellow, green and blue so they stand out from the gray architectural structures. The addition of color humanizes the otherwise sterile and mechanized atmosphere of this closed, self-sustaining system filled with isolated figures. In Panopticon I, the scene rotates from a fixed centered position and transitions from interior to exterior as well as from day to night within the ever-morphing gridded architecture.

In the twenty minute animation Exosphere Bennett creates a prison-like space in which featureless male bodies perform mechanical tasks, like hamsters endlessly spinning on a wheel, yet controlled by unseen masters. Because Bennett creates animations, he can pan through environments and change the camera’s focus from distant to close up. In this respect, he develops more expansive worlds in a single work than either Piranesi or Escher could in order to create fascinating, mechanized environments.