Your cart is currently empty!

The Forever Now

Curated by Laura Hoptman and on view at MoMA through April 5, “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World” attempts to identify a distinctly current impulse to select and recombine styles, materials, iconography and other references from a broad range of art history. It argues that the resulting “timelessness” achieved by these paintings is only possible because they don’t represent the present, but rather reflect the obsessions of the participating painters with their creative antecedents.

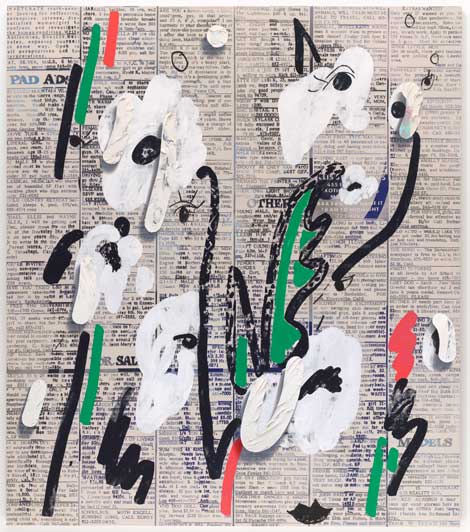

That so much timelessness is happening just now would seem to indicate something distinctive about “now,” so this thesis is self-defeating. The exhibition isn’t particularly illuminating, though it includes much interesting work. Nicole Eisenman, a splendid colorist, contributes five commanding, radiant, full-face heads, some of them studded with collaged photos of African tribal objects. Michael Williams also uses photography—inkjet prints on canvas—which he works over in squiggly airbrush, picking out mysterious figures and echoing the horizonless, wiggly world of the Jean Dubuffet exhibit three floors below.

Who knows if Dubuffet is on Williams’ radar, or if Michaela Eichwald knows Stephen Mueller’s horizontal, panoramic, gestural paintings of the 1980s, which her work instantly recalls. Julie Mehretu’s paintings are clearly derivative of Cy Twombly’s—but then, is “derivative” a valid criticism in light of this exhibition’s premise, which suggests that an ostentatious display of one’s sources is an emerging practice in painting?

By contrast, Mary Weatherford fully inhabits her work; her neon-meets-Color Field idea can be hit-or-miss, but here it shines. Amy Sillman’s riffs on the Cubist still life are not her strongest work but, as one of the first painters to reconsider Abstract Expressionism after years of critical ridicule, she is a natural for this show.

The choppy, tactile surfaces of Mark Grotjahn’s paintings are perfectly in step with their claustrophobic close-ups of bizarre masks. Richard Aldrich’s sedate, nearly monochromatic Blue Sea Old Wash, at about 14×11-inches, operates on an oceanic scale that dwarfs his much larger, stylistically aggregative canvases. A three-panel, 18-foot-high painting in scorching red, blue and yellow, Variable Foot by Matt Connors includes subtle chromatic drama at the seams, where the colors meet. This is the stuff the camera often misses.

Oscar Murillo contributes 11 generically abstract paintings in mixed media on sections of linen and canvas stitched together like he’s using up leftover-scraps. Most are loosely folded and heaped on the floor; viewers are invited to leaf through them and spread them out. This tactic would be more interesting if the paintings varied substantially, but they are utterly fungible. Josh Smith’s production is represented by a grid of nine 5×4-foot canvases. His repertoire of references is stretched to the breaking point, which I guess is the idea. Meanwhile, an area in the middle of Charlene von Heyl’s Carlotta reminds me of a certain Arthur Dove painting from 1938. I really like that Dove, so I like Carlotta, too.

Filling out this overfull show are works by Joe Bradley, Kerstin Brätsch, Rashid Johnson, Dianna Molzan and Laura Owens. Among the many criticisms that have been leveled at “The Forever Now” is that it treats painting as a closed system, but that’s not my objection. Painting is, in fact, a language—that’s an outcome of its having accrued the “historical baggage” some nonpainters complain about (and which painters like those in “The Forever Now” revel in). But this attempt to rehabilitate “pastiche as a conscious strategy” means wearing your research on your sleeve, rather than integrating it into a distinctive voice.

At least since 17th-century English artists made the customary tour of Continental museums, painters have ransacked the art of the past for ideas about how to proceed with their work. Certainly, instantaneous online access to digital images of art from an enormous range of times and places provides contemporary artists with unprecedented research opportunities. Contrary to this exhibition’s thesis, artists have always done so. We do more of it in the age of the Internet than before, with far greater ease, but the essential activity is the same.

Even during periods of a dominant aesthetic, artists working that “-ism” individuated their take on it through hybridization of sources—think of Willem de Kooning’s voracious but selective art-historical appetite, or Richard Serra’s. Laura Hoptman helpfully distinguishes contemporary atemporality, which is not particularly critical of its sources, from 1980s-style appropriation. But quotation as homage—or as theft—is something that most serious artists have pretty much always done in the effort to stake out imaginative working space.

Ends April 5, 2015; moca.org