Your cart is currently empty!

Category: features

-

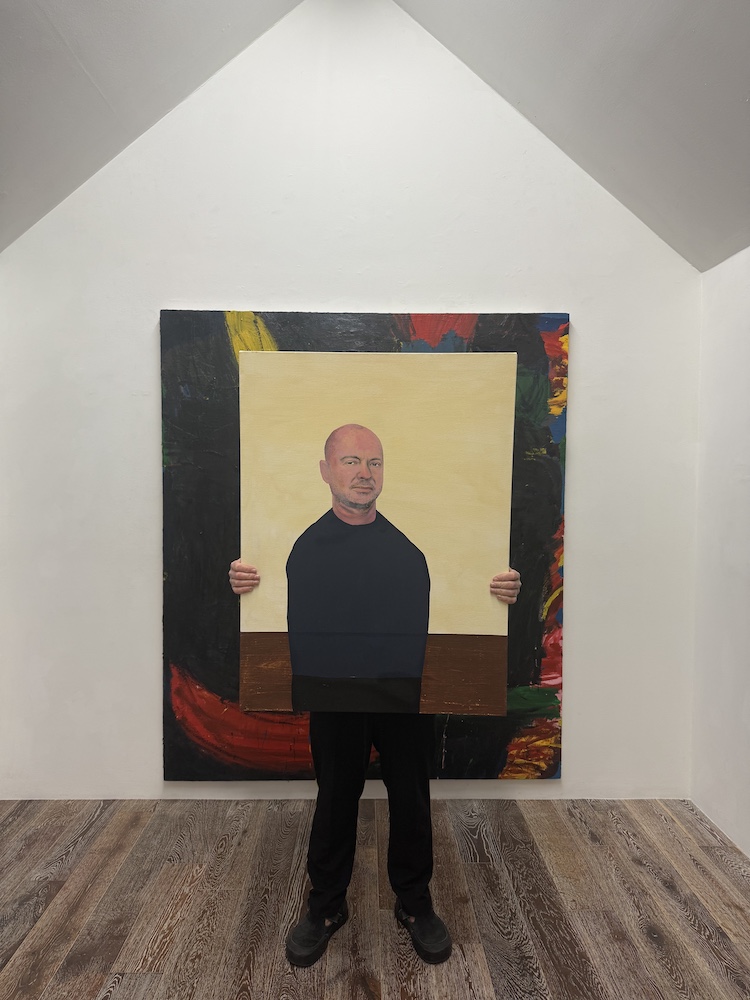

COLLECTORS CORNER: Danny First — (print exclusive)

Tell us who you are in 50 words or less:

I live, collect, and breathe art. For the past ten years, I’ve run the La Brea Studio Artist Residency, The Cabin LA (according to ArtNewspaper, “Per square foot, the most influential gallery in LA”), and The Bunker LA. Two alternative exhibition spaces in LA. I also sculpt.

What do you require from an artist you collect?

Originality. Even if other artists heavily influence them.

Favorite place to meet with an artist outside of their studio or your home?

I take my visiting artists to exhibits that I think they should see & also to In & Out.

This article is available in print and in our digital edition. To read the full article, please subscribe.

-

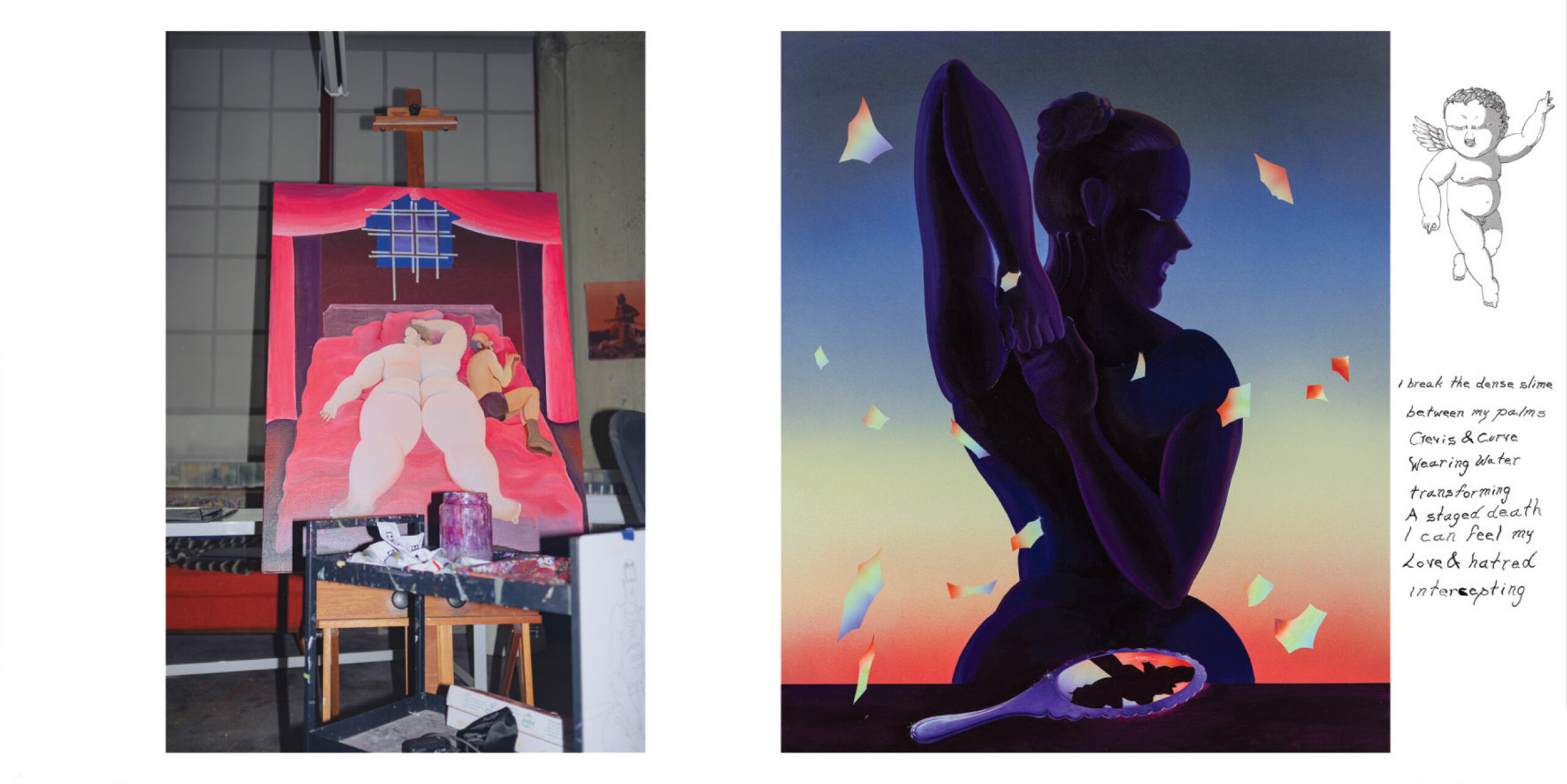

An Artist Answers Questions — (print exclusive)

with Linda FrankeTop 3 Songs?

Portishead — All Mine

Ziúr

J.I.D. — Surrounds Sound (feat. 21 Savage & Baby Tate)This article is available in print and in our digital edition. To read the full article, please subscribe.

-

STAYING SANE(ish) WITH DR. TRAINWRECK — (print exclusive)

The Picture is, or Should be Anyway, of an Entire PersonIf you are reading this magazine, you might be an artist. Or you have a friend who is, or perhaps you are at a Barnes and Noble flipping through Artillery while you wait to purchase an oversized coffee table book of Rock n Roll photography for some guy’s housewarming party in Silverlake. No matter the circumstance, I can safely assume you, or the artists you know, or even the guy who just bought his first home (with help from his producer dad, obviously), has at least one mental health issue.

This article is available in print and in our digital edition. To read the full article, please subscribe.

-

AND THEY TRY TO CONVINCE YOU APPLE TV IS REAL

(Excerpt from an essay).

Hugh Jackman makes a brief cameo in the third Night at the Museum movie aptly titled Secret of the Tomb, where he plays himself playing King Arthur in a stage production of Camelot. Jackman as Arthur gets visited by Sir Lancelot, played by Dan Stevens; but he’s not Dan Stevens playing Dan Stevens playing Lancelot, he’s the real Sir Lancelot brought to life via a magical Egyptian tablet. Lancelot breaks into the theater and jumps on stage, expecting a warm welcome from his sire. But Arthur is no Arthur, he’s simply an Australian actor pretending to be a funnier and less gay version of himself playing King Arthur. “Buddy, this is all just pretend.” Jackman as Arthur tells Lancelot, who by this point is having a violent crisis of meaning. “None of this is real.”

Right about then was when I realized just how fucking grossly drunk I’d gotten off of the green apple BeatBox. That was my first time trying one of those drinks. I kept seeing all the little badass Mexican kids in my neighborhood drink them at 8 in the morning on their way to school. 11.1% ABV seems about right. The drink was disgusting, but appropriate. I needed to get very drunk very fast. I had a long brutal night ahead of myself. 5 more Ben Stiller movies I had to get through, and it was only 6pm.

I’m still not sure why I decided to do that on a Saturday afternoon. A subtle homage to the degeneracy of the pandemic era perhaps. Wasting your time was so much more fun when the rest of the world was joining in.

I didn’t really expect a Night at the Museum movie to be so lore heavy. Lots of mystical ancient Egyptian curses and macguffins. Not enough jokes. I think Ben Stiller was embarrassed to be in this. Lifeless in every scene. Apparently the sentiment was shared by the entire cast, a movie full of actors who think they’re well beyond this kinda stuff. All except for the monkey, who shocked me with her nuanced performance. Her name is Crystal the Monkey.

In college my thesis professor told me a story about Ben Stiller. How he helped Stiller shoot a skit that landed him a gig on SNL, his first big breakout. A parody of a Scorsese film The Color of Money. And apparently Stiller was such an entitled nepo-baby piece of shit, overworking his unpaid cast and crew going full Kubrick, that my professor got into a fistfight with him. Which supposedly is why he’s blacklisted by “the big comedy” to this day. I’ve always had a suspicion that Stiller was up to no good. The story’s most certainly fake. But good enough for me. From that point on my beef with Stiller was personal. That was 5 years ago.

5 whole years ago. Crazy! Time flies even when you’re not having fun. Los Angeles in the middle of the pandemic was a special time and place to be a part of. Maybe it meant something. Most likely it didn’t. But there was madness in any direction at any hour. The People’s Coalition reclaimed Round Two Hollywood. We had successfully shut down Tenants. There was a universal sense that whatever we were doing, it must’ve been right. Because we were fighting for something. Or something like that.

Permanent Midnight is a 1998 addiction drama that is nothing new. Every actor has the impulse to drop 30 pounds and play a junkie to get taken seriously. But who’d want to watch a movie where Derrick Zoolander sticks a dirty heroin needle up his neck while his infant baby watches him tweak? What a sweaty, boring time.

Right around when the LAPD found a dead 18-year-old inside a homeless encampment in Echo Park is when the wave finally broke and rolled back. She was an honors student from Oceanside, “met and fell in with the wrong crowd at a BLM protest” her mother said. Died of an overdose. What followed was one of the largest police actions in LA history, and hundreds of brand new surveillance cameras were installed all around the park. Out with the old and evil, in with something much, much worse. At least the boomers stopped Vietnam before rendering themselves useless. We learned how to coexist with our war. We were simply playing pretend, to no effect.

Who is the real Ben Stiller? What is Ben Stiller?

I tried watching Meet the Parents on Roku TV via Hulu, but it required a separate Showtime Plus add-on. None of those things sound real. And I was not going to pay 4.99 to Meet the Parents. So instead I put on Tropic Thunder.

Tropic Thunder means a lot to me, as much as I don’t like to admit it. I think it was the first ever naughty movie I got on DVD. It’s easily Stiller’s best work, maybe his only meaningful work. A movie about hacks and has-beens. An interrogation of the very idea of pretending. There’s a scene where Robert Downey Jr is in a yellowface on top of a blackface—all while he’s playing an Australian (Aussieface?). This is a story about what’s real and what isn’t.

It was around 5:30 in the morning when I finished my 6 movie Ben Stiller marathon. Some other titles include the Meyerowitz Stories, Reality Bites, and Brad’s Status. My beef with Stiller now extended to the entire Gen X population. So damn whiny. My head was spinning and my nose was numb. An inexplicable wave of sadness came to me. Beautiful way to start your Sunday.

When I said earlier that every single (human) actor in the third Night at the Museum movie was phoning it in, that’s everyone besides Robin Williams, returning as President Theodore Roosevelt. In what would be his final film appearance before his tragic passing, Williams delivers such a tender and loving performance that feels grossly out of place. The film ends with him, alongside all the other museum exhibits returning to their still, lifeless forms. Shenanigans no more. Magic was dead, so was the franchise.

“It’s time for your next adventure,” Teddy Roosevelt says. Repositioning himself one final time before his consciousness ceases to exist. “I have no idea what I’m gonna do tomorrow.” Stupid fucking Ben Stiller says. No idea why he’s the one getting consoled and not the other way around. And Robin Williams says, “How exciting.”

And I’m not watching no fucking Severance.

-

STAYING SANE(ish) WITH DR. TRAINWRECK — (print exclusive)

Ask Dr. TrainwreckWhat is the Purpose of All of This? And by This, I Mean Life

Dear Dr. Trainwreck,

I have recently gone through a life change (a major breakup and move) and am having a hard time finding my footing. The close friends that I thought would be there for me disappeared shortly thereafter, and I’ve spent the better part of the last several months trying to nurture new friendships with people who are interesting and engaging. My question is: what is the purpose of all of this? And by this, I mean life. I’ve tried to live most of my life making choices that I wouldn’t regret on my deathbed—but I find myself now in a position where I’m wondering if that even matters. It feels like everyone is just making it up as they go along, and also that everyone is so lonely. How does one find or cultivate joy when everything seems inconsequential?

— Tumbleweed

Dear Tumbleweed,

How I wish there was some magical thing I could write to you, some optimistic, practical, feasible way forward, a comforting missive assuring you there is an order and purpose to it all. This I sadly cannot do, but I will address what I can without knowing specifics of your particular situation…

This article is available in print and in our digital edition. To read the full article, please subscribe.

-

LUDOLOGY

I’m…

…located at an arts fortress that is always free, but you should make a reservation.

…an extremely sexual painting whose description of what the group is doing is written in a non-offensive language that the entire family can read.

…small (about the size of a piece of paper) and created in the early 19th century by a Frenchman.

Send a selfie of you in front of your guess so we can see both clearly. If you guess correctly, we will send you a coupon for a treat from Lemon Poppy Kitchen (3324 Verdugo Road, Los Angeles, CA 90065). Good for the first 20 correct answers! Game lasts until June 30, 2025.

Send your answer to: editor@artillerymag.com

-

JOHN WATERS’ BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION: THE NAKED TRUTH

The WallisCan John Waters offend anyone these days? It hardly seems so. “I’m tired of being respectable,” he quipped at his show, “John Waters’ Birthday Celebration: The Naked Truth,” admitting he might be relatively mainstream today. He listed all his recent awards, and now he is greedy for more! “I want the Nobel Piece of Ass Award!”

Whether he can still offend or not, Waters doesn’t disappoint. This might be the fifth time I’ve seen Waters on stage, and once again, hilarious and flawless. His sold-out show at The Wallis theater last Saturday night promised to reveal all, and he didn’t hold back.

My first Waters live show was in the late ‘80s in LA and involved a beehive-hairdo contest. I took special care to sculpt my hair big and dress outrageously, but sadly, I wasn’t picked to be in the contest. That was just unacceptable, so I shoved my way into the contestant line—a classic Divine maneuver. I later realized I was probably competing with a bunch of drag queens, which was not exactly fair!

So on Saturday, I arrived especially early to people-watch, expecting to see at least a few Divine impersonators and some crazy wild outfits, but there were none. This crowd could have easily been attending a folksinger concert, albeit a gay folksinger. As I sat sipping my martini, the empty seat beside me suddenly became occupied by a young guy in his twenties. He was friendly and we started talking. I jokingly asked him if he felt like he just walked into a nursing home event. He did laugh but defensively pointed out the few young people sprinkled around us. When I asked if he’d ever seen Waters live before, he replied, “No,” referring to Waters as a “comedian,” which jarred me!

That got me thinking about how Waters remains relevant with his varied mix of fans. I’m old-school, as my introduction to Waters was his classic early films, but many fans today haven’t even seen Female Trouble, and their introduction to Waters is more like Hairspray. (I used to roll my eyes when I would hear someone say they love Hairspray, not even knowing about his earlier films, which really put Waters on the cult-status map.)

Waters is a polymath with his fingers in all the pots. He never stops producing, whether it’s a new book, his first novel (only a few years ago), a film, or a live tour. He is constantly on the go and remains a fixture in art and culture. Artforum and The New York Times routinely check in with what his favorite movies or books might be. Everyone wants to know, what does John Waters think of this or that? The Baltimore news media even reached out to see what he thought about the bridge that collapsed, which he told us onstage, seemingly rather amazed himself.

What keeps Waters still so fresh and alive? My first response would be, he’s still fucking hilarious (and stopped smoking years ago). He’s unabashed and authentic. He came on stage with his salvo of rapid-fire jokes: one right after the other, pacing back and forth, no pauses or glitches. Since this was a birthday tour (not afraid to reveal his age as most celebrities), he addressed getting old, and he doesn’t have a problem with aging; in fact, he loves it and finds whacking off to walkers very satisfying. (I must introduce him to John Tottenham’s sexy women-and-walkers paintings series.) He does not refer to himself as a male cougar (Thank God!). What he does have a real big problem with is shitting, and he’s not talking about constipation. I’ve read of a good bowel movement being compared to sex à la Charles Bukowski, but Waters couldn’t disagree more. The very act of unloading he finds a disgusting task—why did God design us this way? The one thing he looks forward to when he’s dead is never having to take a dump again.

Thankfully, we were spared the subject of today’s politics, with one exception pointing out that while all the protests are fine and dandy, what we really need is another Bloody Sunday if we want to make a difference (and he is so right).

He seemed to be even raunchier than ever, delivering his zingers with verve and conviction, snarling and twisting his face when he spat out, “I don’t like strangers touching me in a nonsexual way.” His suggestions for political correctness while talking dirty in bed were a riot and most crude. He makes fun of heterosexuals the way Black comedians ridicule white people. Today’s porn is no fun anymore now that it’s free, and he urges people to fulfill their every fetishism: “Go ahead and fuck that tree, trees are whores!”

Waters was on that night and delivered jokes, dare I say, like a true standup comedian. Known for his dedication to his fan base, he even stuck around to answer questions from the audience afterwards. It appeared once or twice he might have lost his place, taking himself back to the note card on the stool placed onstage with a bottle of water (of which he never took one sip), but that was even seamless as he muttered out loud to himself, “Let’s see, what else do I hate…”

-

LOS ANGELES FESTIVAL OF MOVIES

Artillery on the StreetDAY ONE

Last night, Vidiots at Eagle Rock saw the start of the only weekend of the year where being an indie filmmaker in LA feels like it truly matters as much as it should. As the second edition of the Los Angeles Festival of Movies kicked off, current microbudget stalwart actor Colin Burgess remarked it “probably has one of the best festival names out there right now, because most festivals are doing ‘film festival’ with the abbreviated FF and not FM, of movies.” Of course, he loves the FM and how it reminds him of that other festival about books. Opening the festival was Amalia Ulman’s Magic Farm, an incredibly of-the-moment satire about a group of clueless Vice-style American journalists led by Chloe Sevigny, who mistakenly enter an Argentinian town in the hopes of finding a local musician, only to stumble through increasingly absurd scenarios of fabricated cultural phenomenon and a brewing health crisis they remain ignorant of, all done using a mixed media visual style that can sometimes be described as “Instagram Reels Realism.” After the screening, I bumped into Jake Thiessen, who produces social media video content for a shoe company and for whom the film’s depiction of the exploitation of the attention economy resonated deeply. Regarding the editing of said shoe commercials, “You gotta get their attention for 2 to 3 seconds and build sentences together to get to the point of what people are saying,” says Thiessen, which wasn’t far off from what happened in the film.

Luckily, I got Amalia Ulman’s attention for more than 2 to 3 seconds and briefly chatted about the formal quirks of her filmmaking practice. Coming from a fine arts background, Ulman spoke about how she approaches cinema with a higher degree of freedom regarding working without certain expectations of decorum. Her film deploys a whole host of 360 cameras and GoPros, weaving in digital textures that we typically associate with online content. Ulman’s approach to shooting was so unorthodox that she specifically hired someone to strap cameras onto dogs; footage she remarks she “had to shoot during lunch time, moments that were not officially part of the schedule, even though, in my mind, it was a very important part of the film.” To Ulman, these different cameras are not quite deployed to impede on what we typically consider cinematic but open up a whole host of visual possibilities that emerge when using them as part of your palette. As she remarked, “There are so many wonderful things that you see online, so dynamic. And then you go watch most indie films at Sundance, and they’re all, like, boring.” In Ulman’s embrace of new technology, which captures images without the sheen of perfection, I was reminded of the rough expressionism of post-millennium Japanese cinema, of films like Hideaki Anno’s Love & Pop (1998) and Katsuhito Ishii’s The Taste of Tea (2004) both of which were shot on early DV. It was the mention of Ishii’s film—which, because of its offbeat rhythm and similar weaving of a large ensemble, I stated was the only other film that reminded me of Magic Farm—that made Ulman light up. As someone who grew up at the turn of the millennium, Ulman reflected on the formal experimentation latent to the films she viewed in her youth: Heisei-era Japanese films and Dogme 95—periods of unrestricted discovery and expression that we now take for granted in an indie landscape consumed by a desire for polish, production value, and respectability.

When posed with the question of whether the effort to make a film feel modern by borrowing from the aesthetics of the internet would always make cinema feel second fiddle to content experienced online, Ulman traced her influences further back to the dawn of cinema. “I think that is not just about the quality of the image. But trying to make something beautiful out of it instead of just trying to be trendy,” Ulman said. “Instead of being hyper-modern, I also pay a lot of attention to really, really, really old films. Like for El Planeta, a lot of the weird close-ups and all that stuff. That’s taken from Silent films, right? But because it’s taken out of context, it feels like something new. And I love doing things like that.”

It appeared that pockets of cinematic innovation, whether in the 20s or the early 2000s, swirl around Ulman’s mind and in Magic Farm. In the movie, there’s a wonderful moment where you see each actor’s head superimposed over a field, captured in an iris with soft edges. I thought of all the young Asian women with permed hair and winning smiles adrift within Korean karaoke videos, but Ulman’s inspiration, Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927), was far more profound. It was a formal choice that speaks to how refreshing it is to view a contemporary film whose visual textures confoundingly alternate between highbrow signifiers and purportedly lowbrow digital “brain rot.” Though perhaps it was Ulman’s unique relationship with her edgy Gen X parents, a generation the film playfully skewers through Sevigny and Simon Rex’s characters, that accounts for her outré modern yet playfully anachronistic sensibility. “I rebelled against skaters,” she said in closing.

Writer Ben Petrie and production designer Becca Brooks Morrin. DAY TWO

Amidst a sea of baseball caps, tote bags, and round-rimmed glasses, Adrian Anderson, writer-director of Pomp & Circumstance (2023), remarked: “40% of people here would take a bullet for Mubi.” It was unmistakable that we were at 2220 Arts + Archives on day 2 of the Los Angeles Festival of Movies. Shuffling between screenings and milling around the lobby, I was struck by how familiar I was with the crowd, as if the same 10 to 15 people were going to each film. People who could comfortably tell you that they’ve seen a Straub-Huillet film but are just as likely to follow up the statement with “I wasn’t really in the right headspace at the time, I’d need to rewatch.” In a city dominated by the entertainment industry, it endlessly fascinates me how caring about independent, experimental, or formally daring films has coagulated into its own specific niche, which festival heads Micah Gottleib and Sarah Winshall have seized upon. Naturally, there did not seem to be any USC or UCLA film students in attendance.

My day started with the US premiere of LA-based artist and filmmaker Courtney Stephens’ Invention. Straying away from her previous documentary work, the film could be described as docu-fiction, following actress Callie Hernandez as she attempts to settle her eccentric, recently deceased father’s estate, deliberating whether or not to inherit the patent to his failed electromagnetic healing device. Despite being a transition into the world of fiction, I still saw parallels to Stephens’ previous features, specifically The American Sector (2020), which captures chunks of the Berlin Wall scattered throughout the US and the lives that surround them. While The American Sector saw the grafting of personal narrative onto a larger historical one, Invention sees the grafting of another, perhaps heavily fictionalized personal narrative onto archival footage. Interspersed throughout the film, we see real footage of Hernandez’s father on various morning shows as a crackpot inventor extolling the virtues of alternative healing—footage that Stephens and Hernandez revealed during the Q&A was taken out of context: he was a doctor and not an inventor. Part of the film’s mystique then becomes parsing through what is real and what is fake. Ultimately, what was authentic were the emotions of Hernandez, who utilized conspiracy as a way to process grief. As much as the film can lay claim to the designation of docu-fiction, it also follows in the footsteps of the very modern and very American innovation of cinematic autofiction, gesturing to those that came before via supporting roles from Joe Swanberg and Caveh Zahedi, whose appearances elicited visible gasps from the audience. However, what really moved me were the transitions between scenes, which captured a flickering candle and a restless body of water, as if to suggest there was a kernel of truth in something as seemingly fictitious and far-flung as vibrational healing.

Director Virgil Vernier. Perhaps my first real discovery during the festival was Virgil Vernier’s Cent Mille Milliards (100,000,000,000,000), which had its West Coast premiere at 2220. The film follows a teenage male escort as he wanders around Monaco, lost in increasingly artificial environments while his body gets passed around by the ultra-rich, and eventually finds refuge during the Christmas season with a Serbian babysitter and a young girl whose parents practically own the country. Throughout the film, a famous Mark Fisher adage rang in my head: “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” a state that has become somewhat of a mantra for Gen Z, who have inherited a neoliberal world where any desire for actual material change is laughed off as an unrealistic pipe dream. Throughout the film, Vernier’s characters navigate a country that appears as a simulation, constantly destroying and reconstructing itself, as elegantly signified by imposing shots of cranes hanging in the air, fighting to stay afloat, and using their bodies as a means of survival as the only commodity they seem to have ownership of. What adds to the feeling of displacement is that every character appears to be descended from immigrants (at least in the traditional French imagination), a point I raised that Vernier responded quite frankly to, “Nobody lives in Monaco. Monaco is really a place for tourists. You just pass by. You just stay for a while, but nobody was born there, right? Like the old lady said, she can grow old very fast.” Adding to the feeling of impermanence are attempts by his characters to modify their bodies through artificial means of lip fillers and healing stones as if to forcibly impose a sense of change that appears outside of grasp, something Vernier touched on saying, “It’s very LA—the desire to be always young and beautiful, and because you sell your body to make a living. Sex work is about that.” A fascinating wrinkle to the film is how seemingly sex-negative it is, choosing to affirm rather than combat Gen Z’s neurotic fear of sex, with Vernier voicing his displeasure to see depictions of sex on-screen, something he perceives as a way to commodify the act. This notion is echoed through his focus on sex workers, “At the same time, sex is work, but it’s not pleasure, it’s not intimate. It’s just work, just a way of making a living.” When quizzed about whether he views how we engage with sex today with a level of cynicism, Vernier denied the sentiment and instead gave a direct answer, “We have started to realize this was a myth of sex as something liberating.” In the world of Cent Mille Milliards (100,000,000,000,000), which seems to constantly be on the verge of implosion, sexual freedom under capitalism ultimately appears as another pipe dream for Gen Z.

Capping off the night was the West Coast Premiere of Grace Glowicki’s Dead Lover, which Sarah Winshall described as “the closest thing LAFM had to a midnight movie.” Taking place on various black box soundstages and performed by four actors armed with various wigs and funny accents, Dead Lover is a raucous comedy following a gravedigger who resorts to the supernatural to revive her recently deceased paramour. Stuffed to the brim with gags—speed ramping, Tex Avery sound effects, prosthetics fingers, and the like—Dead Lover elicited the biggest reaction from the crowd, who yelped and squirmed in equal measure. The arrival of the film onto US soil via LAFM, as well as Sundance, signifies a formal coronation of the current Canadian independent scene colloquially named “The New Toronto Bizarre,” a term Dead Lover actor and co-writer Ben Petrie sheepishly acknowledged, remarking “I embrace my brothers and sisters often and passionately.” In recent months, Canadian indie exports have stuffed the screens of microcinemas throughout LA, becoming the fascination of the chronically online cinephile class with films from Nate Wilson’s The All Golden (2023) to Braden Sitter Sr.’s The Pee Pee Poo Poo Man (2024) to Petrie’s own The Heirloom (2024) which has a screening booked in the near future. When asked about what seems to be in the air up north, Petrie responded, “I would say that our country’s cinema is pretty bad when it’s trying to imitate America. It’s at its best when we embrace our position as a sideshow and play in that space. I think that the freedom of doing our own thing and not trying to be ‘Hollywood of the North’ creates the best work.”

While having a captive Canadian audience, I was able to air out something that has been plaguing me for the past few months: there’s a Canadian sound designer also named Matt Chan who keeps getting “Special Thanks” credits in these films, including Dead Lover. There are only so many times I can get a DM from someone saying that they spotted my name in the credits of Matt and Mara (2024), only for me to reply that I’ve never met Kazik Radwanski, Deragh Campbell, or Matt Johnson in my life, nor stepped foot in the beautiful city of Toronto. I was told that Canadian Matt Chan is “the best sound mixer in Toronto,” “the bomb,” and “the best.” For the sake of IMDb credit, I suggest one of us change our name. I can be “Matthew A. Chan”, taking after my actual middle name, “Augustus,” which I usually show off on my ID as a party trick, much to the bemusement of others, and maybe he can be “Matthew B.”

Julian Castronovo. DAY THREE

Throughout day three of the Los Angeles Festival of Movies, whenever I told someone I wrote for Artillery, I followed it up by saying that if they told me something really funny it would end up in the article. But nothing made my ears perk up quite like a statement from Max, a gaffer on Dennis Cooper and Zac Farley’s Room Temperature, which had its world premiere last night. When asked if he liked the movie, Max said he couldn’t really watch movies anymore and that instead of working on movies, he wished he could spend his time setting up gigantic art installations with beautiful LED screens, projects which could, unfortunately, not gain any funding. His comment made me consider how many people trying to hack it out in independent film today (an industry seemingly in the state of decline) are merely stragglers from the world of fine art (also in decline) looking for something to do. However, an extended chat with festival co-founder, head programmer, and Mezzanine head honcho Micah Gottlieb revealed a much more charitable estimation regarding the handful of fine artists-turned-filmmakers in this year’s lineup.

My initial question to Gottlieb was if he was consciously looking to program films that captured a texture of modernity that felt absent in most contemporary cinema. His reply was that the selection process was more intuitive and that “One thing that I’m really attracted to is artists who are people who are—I mean, okay, yeah, sure, everyone’s an artist—but people who are coming to cinema from the arts, rather than from a film school background. I’m not saying that those movies are automatically good or interesting, but I think that in the case of Amalia and in the case of Julian Castronovo—who went to CalArts—you have these films that are more informed by theory, contemporary art, and personal practice. I’m excited by movies that feel like they’re taking the risks and trying new things out.”

Micah Gottlieb. Castronovo’s film, Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued, which had its West Coast premiere at 2220 Arts + Archives, was, as advertised, a work that defied easy categorization. The film follows Castronovo himself as he traces his life from art school burnout to would-be detective and filmmaker. We see Castronovo unraveling a mystery of art forgery that starts from a postcard of a painting of a fawn and a copy of Don Quixote found in his walls before moving through a world of Chinese diasporic forgers, fake Mubi business cards, and ill-fated trips to Prague. Formally, the film could be described as an essay-film akin to Orson Welles’ F for Fake (1973), as it uses a fictitious documentary style to expose a similar world of art forgery, deception, and the artifice inherent to the cinematic medium. At times, Castronovo’s film—which features no footage from professional cameras, instead remixing MacBook Photobooth sessions, screen recordings, scanned images, and archival DV footage—resembles an elevated Screenlife film. The nascent film form was pioneered by Timur Bekmambetov (director of Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter) and places all of the action on a desktop, something now echoed in iconic films like Unfriended (2014), Unfriended: Dark Web (2018), and Searching (2018). Most of Debut occurs superimposed over the black wallpaper of Castronovo’s laptop screen as the mystery unravels through browser tabs and hyperlinks—a curious example of how aesthetics typically considered lowbrow and “cringe” (Unfriended being known to produce scathing reaction videos from YouTubers intended to entertain pompous 14-year-olds) can converge with the seemingly contradictory avant-garde ambitions of the art world. In my mind, you can define, to some extent, the era a film was made in by how it formally replicates the effect of a drug popular at the time: the frenetic pace of Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985) akin to cocaine, the sluggish half-hearted haze of Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer (1979) akin to heroin. With Debut, Castronovo truly stakes his claim as a Gen Z filmmaker by making what is perhaps the first Ritalin film, one which replicates the experience of going on endless online deep dives while on ADHD stimulants. When asked if the film would have been possible without the pharmaceutical industry, Castronovo replied, “No,” and when asked how much Ritalin he did while making it, he likewise curtly replied, “A lot.” What comes with said deep dives is a voracious appetite for reference points concocted via Google search, which Castronovo directly presents by drawing comparisons to Raymond Chandler, Jorge Luis Borges, Michael Snow’s So Is This (1982), and Hollis Frampton’s Hapax Legomena I: Nostalgia (1971). When asked about the film’s conspicuous display of influences, Castronovo answered, “I mean, the conceit of the film is to copy everybody until you’re not copying anymore.” Castronovo’s highly individualistic approach to filmmaking, writing, directing, and editing the film himself with very little outside help, is, in his eyes, an attempt to render the act more akin to a studio practice rather than the stressful, overstuffed, and overstaffed sets emblematic of film school productions. Through his practice, he seeks to address “the paradox of authorship, where you feel as though the process of authoring something is the same process as becoming a person, but it’s also the same process of disappearing as a person or unbecoming.” In an era where it feels increasingly difficult to do anything that hasn’t been done before, it is refreshing to see someone surrender to the excess and, though buried and suffocating under piles and piles of references, be a distinct cinematic voice.

Concerns about the dysfunctional relationship Gen Z has with contemporary cinema tend to rattle in my head, and I bemoaned to Gottlieb that when I moved to LA three years ago to attend film school, I was dismayed to discover my peers’ lack of interest in any work outside the mainstream. It was easy to talk about Michael Mann, but once I brought up Chantal Akerman the well dried up save for two or three other people. Because of this, the programming of Mezzanine and LAFM has become somewhat of a balm for me and people like my friend Coleman Weimer, a USC film production graduate student who sees going to these screenings as akin to taking his medicine: at the very least it provides a space where caring about the thing you care about doesn’t feel insane. Naturally, questions of Gottlieb turned to how the wider public could be swayed to leave the house to take a chance on seemingly inaccessible arthouse films, with the answer boiling down to “context, curation, literacy.” As Gottlieb detailed all the ways to ensnare a younger audience— through building a social media following, taking on non-film world guest programmers a la Rachel Kushner, providing third spaces to interact in a post-Covid world and so on—I was once again confronted with the depressing realization that film as a medium has greatly lost its relevance to the public, especially requires jumping through so many hoops just for someone to take a chance on something new. Though, as evidenced by the hefty box office haul Jared Hess’ A Minecraft Movie made within the past three days of the festival, the theatrical experience is not quite in complete decline, as Gottlieb remarked to me, to whatever extent, “Everyone loves movies.”

One of the most insightful comments Gottlieb made was regarding the original goal of Mezzanine, which was to bridge the gap between the thriving fine art scene in LA and the world of film, which seem to rarely intersect. Because most of today’s formal innovations in cinema seem to trickle down from the art world, the separation between the two always feels arbitrary. But nowadays, it feels like both industries are becoming increasingly cloistered off, catering to the whims of the few who still seek out some sort of aesthetic edification outside their homes. Though as much as I can complain, try as I may, I could not deny the sensorial bliss I felt while watching the West Coast premiere of the restoration of Robina Rose’s Nightshift (1981): a recently rediscovered British proto-slow cinema film that follows a hotel receptionist and the guests that wander in and out of her lobby. Astoundingly, the film predates both Chantal Akerman’s Toute une nuit (1982), which similarly features the constant entrance and exit of bodies as they melt into the night, and Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn (2001), which share a focus on capturing the physical labor involved within the upkeep of public spaces. Suffused throughout the film is a wonderful levity and a lack of care for realism akin to Derek Jarman and Peter Greenaway. While watching a sequence that cycles through the inhabitants of the hotel—an elderly man in pitch darkness front lit by a television screen and a group of women having a pillow fight, feathers fluttering through the air, filling the frame in slow motion—I wondered why anyone would want to deny themselves these aesthetic experiences.

Zac Farley and Dennis Cooper. It felt ap then that, in keeping with the theme of film industry outsiders, the day ended with the world premiere of Dennis Cooper and Zac Farley’s Room Temperature. Neither Cooper, the writer of such novels as The Sluts (2004) and cult hero of the Los Angeles alt-lit reading elite, nor Farley, a visual artist, come from a traditional film background. Room Temperature is Cooper and Farley’s third collaboration after the anthology Like Cattle Towards Glow (2015) and the French-language Permanent Green Light (2018). The film follows the exploits of a family living in the deserts of California, who turn their eerie, prefabricated home into a haunted house. As they move deeper into the realm of simulacra, radically recontextualizing the space they inhabit, the macabre and the mundane seem to blend through various emotionally detached acts of violence. Farley gave a comparably clear-minded explanation for their fascination with sterile, modern homes, citing the discomfiting lack of decor as being able to “completely focus the film’s attention and the camera’s attention on the characters,” citing “one shot in the film that we call ‘the cake shot,’ because, until the characters walk into the frame, if you sort of tilt your head, it can look like the most beautiful kind of postmodern wedding cake.” The film’s lack of conspicuous visual embellishment comes in hand with Cooper’s desire to be “kind of transparent,” and present a “very focused and very controlled and designed world.” The delicate and at times shocking balance of tones captured within Room Temperature comes encapsulated in the conceptual contradiction of the home haunt, which Farley sees as “very crafted, beautiful things” that also has an “excessive violence, gory and, horror film-like quality.” Adding, “When you go to a home haunt, you can be in the hell room, and then suddenly it’s like Alice in Wonderland. There’s a lot more freedom in some of these spaces. The toolbox is infinite.”

The home haunt in Room Temperature is the perfect vessel to house the multitude of personalities Cooper and Farley have collected by casting various artists, each with their own personal practice, as different family members. In a way, their approach to performance in this film directly works against the flat Bressonian style of Permanent Green Light, allowing for abrupt shifts in emotional affect. In Cooper’s estimation, “As long as the, the tone and the context is really controlled, very neutral, and very empty, you can allow the performances to happen in a more flagrant, more theatrical way. But the context kind of squeezes them so they never become silly, or overwrought.” With their troupe of non-professional actors, Cooper witnessed how they “had to construct these emotions and construct these things in a way that felt really real—really real to them—so that it felt very sincere.” In the artificial space of Room Temperature’s haunted house, it can be hard to discern the real. The magic of the film comes from tumbling through the rooms of Cooper and Farley’s creation, which defy any neat cinematic logic, positioning the absurd and grotesque as inexorable features of the everyday.

Charlie Shackleton. DAY FOUR

Whenever approaching someone at the festival, my go-to icebreaker would be, “What is the worst and best part about being indie in LA?” a question that I quickly realized did not apply to everyone but usually elicited similar answers. The best among them was from Tyler Taormina, head of LA-based film collective Omnes Films, director of Christmas Eve at Miller’s Point (2024), and producer of Alexandra Simpson’s No Sleep Till, which had its US premiere yesterday at 2220. He answered, “What I love, of course, is being in a place where all my closest friends are and collaborating with them on films. As well as seeing films in the best theaters in the world. What I don’t like is how expensive it is—how a croissant is $5.” The conflicting desire for creative freedom and financial stability seemed to be a recurring anxiety amongst everyone I talked to, even if we all momentarily inhabited this bubble where independent film felt like the most important thing in the world. A bubble that would inevitably burst as the festival drew to a close on Sunday, with many in the crowd likely clocking into their day jobs at vertical Instagram reel content farms the next morning. This sentiment was echoed by Sarah Winshall, co-founder of the festival and head of production company Smudge Films—which has produced works like I Saw the TV Glow (2024) and Good One (2024)—who said, “The best part of being indie in LA is that I don’t have to commute across town to go work in a studio office. The worst part is that it’s really hard to get paid to do your job.”

My conversation with Winshall, who in the eyes of a precocious film student is someone doing meaningful, successful work, tended to focus on the current precarity of the film business where even hitting traditional barometers of success doesn’t always translate to a living wage. When asked the big question of where everything is headed, Winshall answered, “I think the future of it, at least for me, is that we’re going to be forced to treat film like an art form. Because indie cinema that’s personal and vital is not commercial. There was a time when it was, mostly a long time ago, and there was a slow tapering off and now a real drop-off for that to be something viable. It’s a rare exception that an art piece that is personal is also part of a commercial American film. It’s going to be less and less a job and more and more passion, art, and art practice.”

This positioning of independent film as personal practice was also suggested by Julian Castronovo the day before in his film Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued. It further rang in the back of my head while watching Charlie Shackleton’s Zodiac Killer Project, which had its West Coast premiere after making a splash at Sundance. The film follows Shackleton’s attempt to adapt Lyndon E. Lafferty’s book The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silenced Badge into a true crime documentary, a process that implodes, leaving Shackleton to resuscitate the pieces by feverishly describing what would have happened in his film over shots of locations booked for the would-be shoot. Shackleton is best known for his film Paint Drying (2016), which is perhaps more a conceptual practical joke than an actual film, seeing as it forced the UK censorship board to actually watch 10 hours of paint drying. His punkish spirit continues to shine through in Zodiac Killer Project. For most of the film, Shackleton stays committed to a metatextual skewering of the tropes of true crime, oftentimes by directly showing us clips from Netflix documentaries and making comments on their aesthetic homogeneity. What struck me about the film was how much it hinged on the charms of Shackleton himself, with his constant monologue dictating the flow of footage dispensed to the viewer. When asked if he was mindful about projecting a persona, Shackleton answered, “I would say it’s no more of a persona than when you’re in a bar telling a story to your friends. It’s a rehearsed story, but I quite consciously chose not to script any of it. Because I knew I’m not a good enough actor to perform written words convincingly.” In terms of form, Shackleton’s film feels particularly well-suited to the current age, where we tend to be as interested, if not more, in people than the work they create, developing parasocial relationships with Instagram accounts. It is this same sentiment that fuels the current psychotic cultural fixation with podcasts and streamers—who can somehow sway elections—and Shackleton very astutely mixes both true crime and TrueAnon within the cinematic medium. However, that’s not to say his work is without precedent. I was reminded of both Caveh Zahedi’s The Show About the Show (2017), in the manner in which every moment is a process of describing the making of the work you’re watching, and the audio-visual detachment of the films of Marguerite Duras, whose Le Camion (1977) revealed itself to be a similar object of fixation between me and Shackleton. Unsurprisingly, Zahedi and Duras are both artists known just as much for their public personas as their work. What Zodiac Killer Project actually reminded me of was Pomp&Clout’s music video for one of the best Young Thug songs, “Wyclef Jean,” which features constant running commentary explaining how incredible the video would have been if Young Thug actually showed up for the shoot. When told about this observation, Shackleton replied, “That’s a flattering comparison.”

After various instances of lobby loitering, hitched car rides, and alleyway lurking, and after seeing every new work in the lineup, I tended to express my shock (to whoever was around to listen) at how much I enjoyed every film—a rarity at any festival. I wouldn’t chalk this up to a perfect alignment of taste with Winshall and Micah Gottlieb or festival inflation—which I realized I am mostly immune to, having been surrounded by disgruntled faces at last year’s Cannes after I told them Emilia Perez (2024) was bad immediately post-screening. It was because every film felt like it was attempting something new and occasionally something consciously alienating. However, my positive bewilderment was partially tempered by the realization that most of these films would not easily sell to wide audiences or distributors. A notion Winshall articulated in a more level-headed manner, saying, “I’ve been really noticing lately is that there’s no dearth of movies being made. That’s not an issue. We’re living in a time of just a wealth of movies and good movies being made all the time. The thing that’s tough is finding a way to get them seen and to get people excited about them. For me, as a film producer, sometimes it feels a little irresponsible to be contributing to this big pile of movies that need a place to go. Maybe I’m just easing that guilt by providing us with a place to put our films.”

Alexandra Simpson and Tyler Taormina. The ability to transition from niche, hyper-limited appeal to the still niche but far less limited world of major film festivals and arthouse theatres across the country is something I’ve admired about the films being produced at the LA-based collective Omnes Films, who premiered both Christmas Eve at Miller’s Point and Eephus (2024) at Director’s Fortnight at last year’s Cannes. Both films went on to have fruitful domestic runs. What impresses me about their work is how they’ve managed to produce films that consciously draw from the slow cinema world of filmmakers like Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Chantal Akerman, rendering their chosen locations in vivid ethnographic detail while still retaining the offbeat comedic charm of the American indies of Hal Hartley and Richard Linklater. The film they presented at the festival, which had its US premiere yesterday, was Alexandra Simpson’s feature debut No Sleep Till, which captures the lives of the various residents of a coastal Floridian town who each find ways to cope with an emergency evacuation order triggered by an impending storm. The film weaves between their perspectives as they navigate Florida’s landscapes, which themselves become abstract smears of light and color. With much respect to Tyler Taormina, Carson Lund, and Jonathan Davies, I found Simpson’s picture to be my favorite Omnes Film thus far. Constructed from the Paris-born Simpson’s memories of summers spent in Florida, the film uses the lens of nostalgia to refract the collective’s fixation with texture and detail. Most images in the film seem to be delivered via an intermediary source: captured through the side mirror of a car, reflected and distorted through bodies of water, or replayed through laptop screens, which imbue the town with hazy, impressionistic, and inexact qualities. The focus on immateriality was further echoed by a comment Simpson made in the Q&A, stating that the film did not start with an image but “started with the sound of thunder, which is constant, and these warnings that you really do get, too, because I have been there during pending hurricanes. There’s a sort of electricity in the air that is contagious, and everybody’s sort of put together through this experience, this weight. It’s all tinted with sound because the news is always somewhere in a bar or in people’s homes.” In the shadow of impending doom, Simpson mainly foregrounds tender emotions in a sincere register that never feels maudlin: of two male friends navigating a move out of Florida with the implicit fear of losing one another, or of the first fruits of adolescent love delivered via handwritten notes. It is impressive how much character work is done in a film with so little dialogue or attention on any one individual. The film’s best sequence is abstract: the camera lingers on the shadows of partygoers intermingled with colored strobes, their bodies swaying to ML Buch’s “High speed calm air tonight.”

It always feels revelatory when confronted by a fresh cinematic voice working in an uncommon register like Simpson. It’s also always frustrating to think of the many distinct filmmakers throughout the country dissuaded from a career in film because of its supposed economic instability and lack of funding. Winshall gave a very direct response when asked about this: “You’re not making a living by trying to pursue this. Maybe the answer is the gig economy. Maybe the answer is that you also use your skills to make wedding videos. I don’t know. It sounds depressing to us because we were told that we’re supposed to pursue our passion as a career, and I wish that were something that I could say could happen. That being said, I don’t think that’s possible right now for most people. I know a lot of people who have put their lives on hold, waiting until the moment when their passion is going to become their career in a successful way. I wish that they would just go make stuff.” When I inquired about what Winshall thought fresh film school graduates should be doing, she quickly replied, “Watching movies.” It sounds obvious, but as anyone in film school right now who actually watches movies knows, it’s something startlingly rare amongst their peers.

Neo Sora. It was fitting then that the festival came to a close at Vidiots with the West Coast premiere of Neo Sora’s Happyend, which had its world premiere at last year’s Venice Film Festival and captured many of the latent anxieties regarding the future I’ve endlessly rambled on about—even if the film admittedly felt more like typical festival fare than the various oddities that littered the past 4 days. Sora’s debut narrative feature is set in a near-future Japan headed towards fascist rule as more and more civil liberties are suspended under the pretense of earthquake safety measures. The film follows four students whose high school transforms into a microcosm of Japanese society as a new surveillance system named “Panopty” that monitors their every move is installed. What follows is an eruption of protests as the students are confronted with various hard choices and the question of whether it is right to remain silent in the face of a categorically unjust society. Sora’s film is one that attempts to achieve the epic, emotional scope of other modern coming-of-age classics, such as Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991), which he noted as an influence, and Kenneth Longergan’s Margaret (2011), which position young people as those caught within the throes of history which they remain powerless to change. Though by working so tightly within the manicured aesthetics of current highbrow Japanese cinema—clean digital cinematography and tastefully modern apartments, which many have referred to as “Uniqlo-core”—the film almost feels frictionless in spite of the radical political ideas it attempts to convey. Perhaps one can view the film as working within the conceptual and aesthetic framework of neoliberalism, where every conflict is implicit, with acts of racial profiling conducted on the character of Kou (a Zainichi Korean) being delivered via regimented, bureaucratic policy. There is never any actual violence, only microaggressions and state-mandated checks. The overwhelming politeness of the work did make me yearn for the, at times, ill-conceived angst of a film like Shunji Iwai’s All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001), which similarly tackled growing tech anxiety within Japan. However, I was quick to realize that the film probably resonated with the mostly millennial audience because of the lack of conflict. As Sora reminisced in the Q&A about his involvement in Occupy Wall Street, I wondered how many of the millennials in attendance had a similar experience of being starry-eyed, believing they were doing something actionable for a cause that in reality, did very little to move any needle, realizing how powerless they were in the face of neoliberal hegemony.

Where the film does find resonance is in its parallels to the college encampments that occurred across the country last year in protest of Israel’s occupation of Palestine, which called for schools to divest from funding the State of Israel. Viewing the students of Happyend stage a sit-in in their principal’s office, and despite being shot years earlier, there was an eerie sense of familiarity, one that suggests the historical continuity between student protests. When asked about the parallels, Sora noted, “Basically, what Japan was doing to Korea and these other East Asian countries is what Israel is doing to Palestine right now. There’s a really significant connection between those two things. More and more every day, I can’t believe anyone can be indifferent to what’s going on.” When I inquired as to how he managed to write a film that didn’t fall into complete despair despite taking place in a world where any positive changes seemed impossible, he answered: “You need some degree of hope even to survive, and the fact of the matter is that Palestinians still have hope. I mean, they’re losing it every day. They still have hope that it can stop and they can be free. And if they can have it, then I need to keep it. That’s not necessarily the feeling I had when I wrote the film because I didn’t know anything about Palestine back then, but more and more, I feel that way. I feel like hoping for something new, even in my artistic sense, is also a hope. You need that hope for human ingenuity and creativity so you can believe that there will be a future.”

I don’t think much else needs to be said.

-

Desert X

Since 2017, I have been among the 1.7 million people who have participated in the art biennial-cum-treasure hunt to seek out large-scale, site-specific contemporary art installations scattered throughout the Coachella Valley desert, the land of the haves and have-nots. Not in a white cube, locked away in a walled institution, or behind a paywall, Desert X is a great equalizer, breaking down the walls of the institution and sharing the cultural wealth of art and the wild west with any who wish to seek it out.

Nestled into the perimeter of the iconic wind farms in Desert Hot Springs, Jose Dávila has installed 12 massive blocks of white marble from a Mexican quarry. Harnessing the illusion of exhilarating precarity, he balances pairs of them upon one another, creating towers and cantilevers of brilliant stone that absorb and bounce the desert sunlight, jutting into your field of vision from every perspective. The monumental presence of these unmissable forms of extracted land provokes a consideration of the counterbalanced emptiness that must exist elsewhere, mirroring the heavy weight of the lived reality of so many immigrant communities in the area but not from the area. The act of being together is beautiful, bold, and somber to behold all at once

In Palm Springs, Ronald Rael’s Adobe Oasis imagines a future where robotics and ancient adobe architecture can effectively answer the housing crisis. His open-air, maze-like structure—meant to evoke the texture of the city’s eponymous palm tree trunks—demonstrates the possibilities of a modern adobe tradition 3D printed in locally sourced and sustainable Corona Clay. I wasn’t delighted by its aesthetic—its walls looked to me more like excrement squeezed through a large icing pipe—but the imaginative underpinnings of the alternative future it proposes won me over. As they say, the future is now. The work provokes critical consideration as entire cities devastated by natural disasters are rethinking how to rebuild in a climate crisis. Rael’s installation reminds us that adobe architecture has stood the test of time and offers a glimmer of hope.

Desert X 2025 installation view of Alison Saar, Soul Service Station. Photo: Lance Gerber. Courtesy of Desert X. I was soothed and amused by the imagined architecture of Alison Saar’s Soul Service Station, a gas station for collective healing. Like a friend who acknowledges our troubles and reminds us that we are stronger than any moment of seeming defeat, all who encounter it are invited to refill our troubled, deflated souls with optimistic energy. Its attendant, Ruby, is fashioned in Saar’s signature figurative style, carved from sturdy wood and covered in an armor of salvaged ceiling tin. I felt her protective energy washing over me as words of encouragement by poet Harryette Mullen poured out of the gas pump’s two conch shell-shaped nozzles. The experience felt like a warm hug, gently asking me to slow down and absorb the multitudes of Saar’s layered assemblage sculpture, radiating with the inherent magic of reclaimed materials that carry their own histories of resilience.

Agnes Denes’ The Living Pyramid at the historic Sunnylands Center & Gardens is a durational work covered with flora planted last November. The multi-story living sculpture, a brilliant white stepped pyramid garden bed, is a commanding centerpiece of the already impressively manicured gardens. When I visited it during the press preview in early March, set against the distant snow-covered mountaintops, the sculpture was covered in plants boasting the vibrant greens, pinks, yellows, and oranges of early spring. But everyone who visits will have a different experience as the plants continue to bloom over the course of the installation. When the snow inevitably melts, and the pyramid is in full bloom, the relationship to its site will change, and the aesthetic harmony I experienced will be replaced by the juxtaposition of a fragile garden thriving in the heart of the desert.

Desert X 2025 installation view of Agnes Denes The Living Pyramid at Sunnylands Center & Gardens. Photo: Lance Gerber. Courtesy of Desert X. The impact of Saudi artist Muhannad Shono’s immersive installation What Remains, more so than any other project this year, doesn’t translate to 2D. Images of the work meant to pique my interest enough to pull me out into the middle of Thousand Palms seemed to promise little more than large trash bags blowing in the wind, and the artwork’s highfalutin didactic promising “a state of tremor,” had me rolling my eyes. But my experience of this anti-monument demanded quiet contemplation as I stood observing a field of —yes, rolls of trash bag-like material painted and covered in sand—malleable forms taking on the undulations and palette of the barren landscape. With only the sounds of its fabric scratching against dry desert brush in the wind breaking the silence, it felt eerily like I was at the end of the world, in a future when the last of us who had survived in tents were no longer around to maintain any semblance of home. Is this what is destined to become of us? Is this a fixed destiny, or something that can be interrupted? Is there justice and beauty in ruin? I reluctantly left after 30 minutes of observing the work as it transformed with every breeze, moving through it in quiet contemplation as my perspective of the landscape and possible answers to my existential questions changed with every step.

In today’s world of rapidly accumulating crises, I suppose it’s no surprise these installations captured my heart with their abstracted pedagogies of hope, a welcome reward for finding where X marked the spot.

Desert X 2025

Coachella Valley, California

On view through May 11, 2025 -

ArtNight Pasadena Goes Ballistic

As fate would have it, the biannual “Spring 2025 ArtNight Pasadena” event is taking place on March 14th—winter’s coldest, dreariest, and rainiest day. Accordingly, you select the handful of venues most likely to feature contemporary work, then set off.

An hour and a half and four stops later, you’ve experienced about fourteen seconds worth of satori. It doesn’t seem at all sporting to break out the big critic-of-the-western-world guns for students’ AI-generated superscript, semipro portraiture, or a series of selfies.

Your fifth and last scheduled stop doesn’t seem promising at all. What manner of contemporary art could possibly be intermingled with 16th-century kimonos, Thangka paintings, and Silk Road curios at the USC Pacific Asia Museum?

No sooner have you set foot in the first of what a docent informs you is one of thirteen halls showcasing the lifework of Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang than—kapow! You’ve leveled up to “A Material Odyssey,” literally the most explosive exhibit anyone can attend today in any museum on any continent. Confronted with Crater, a “painting,” if you will (read on), that’s a verisimilitude of everyone’s favorite lunar pockmarks with the bonus of protruding off the canvas ablaze in burnt orange and flint bas relief, you don’t know enough yet about its molecular makeup to realize why it’s so captivating—but you’ve just been instantly teleported to another way station in the cosmos.

Exceptionally well-written wall text and looped videos inform you that Cai’s schtick is “painting” with gunpowder, singeing it this way or that, filming the process from a variety of angles (making sure we catch glimpses of his army of assistants scrambling around). He then springboards from an attention-grabbing gimmick to live happenings on a grand scale—he served as fireworks maestro at the 2008 Beijing Olympics and shocked the bejesus out of a crowd of 5,000 this fall at the LA Coliseum—confirming that this master of metaphysics and purveyor of pyrotechnics also happens to be a gigantic ham.

You’re stunned that this industrious Cai fellow is killing it all over the Pacific Asia, utilizing at least five different mediums ranging from the size of a human forearm (one frozen in time after the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, perhaps) to large-scale compositions the length of stretch limos. Counting this collection, which you’re staring at bug-eyed, as just another stop on the Art Shuttle bus is a bit far-fetched. This guy’s a ringer! It’s as if someone had let Bruce Lee loose in an Intro to Kung Fu class.

Speechless, you find yourself copywriting in your mind, bullet-listing a few of the gazillion reasons to attend:

- Curious about what life on Earth looks like through the eyes of aliens? Seven-panel gunpowder-on-paper works, such as Fetus Movement II: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 9—less womb-zoom than a miniature Buddhist monk caught in the crosshairs of a rusty, post-Armageddon gunsight with accompanying Hanji notations—have you covered.

- Fed up with materialistic holiday excess that almost feels government-mandated? Then you’ll relish watching the ritual obliteration and transformation of a three-story Christmas tree adorned with matte silver baubles into a floating, black haze facsimile of itself on the grounds of The Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., no less.

- Perhaps you’re fascinated by Egyptology and/or you’re a contemplator of the cosmos? Imagine the chi boost you’ll get from hanging a massive mural, such as Inverted Pyramid On The Moon: Project For Humankind No. 3—eight panels of everyone’s fave geometric mausoleums, inverted and right-side-up, augmented with what could be drone shots of the Hawaiian archipelago if they’d survived a wildfire—in your great room.

- Have you ever pondered whether daytime fireworks are a thing? Yeah, they are, as evidenced by videos shot at cradle-of-civilization locales like Florence and Pompeii. Cai himself dramatically intones the “5-4-3-2-1-fire!” countdowns.

- Seen one too many Tibetan mandala paintings? Always wished someone somewhere would nuke all those finely crushed multi-colored minerals into abstract expressionism? If so, I give you Return to Darkness, a lustrous, more molten departure from the gunpowder series. The before: sand shaped into sacred geometric patterns. The after: a non-representational slab of blue-violet marble with an anomalous chalk-white vein

You’re still dreaming up ad copy as you drift off to sleep, imagining yourself climbing Cai’s Ladder to the Sky; 500 meters of golden-colored fireworks latched to copper fuse material, revealed, rung by rung, as it ascends heavenward, oddly exuberant after this ebullient bombardier lit the fuse.

The Cai retrospective is a super surprising and visceral departure from more familiar mediums. It contains angst! Transformation! Ephemera! It’s got to be cathartic to traffic in explosives. There are some things you want to admire from a distance; there are other things you might want to blow up. This art speaks to that latter, almost primal urge—it’s beauty in destruction.

ArtNight Pasadena has come and gone, but the incendiary “Material Odyssey” show runs at the Pacific Asia through June 15, 2025. You can think of a lot worse places to play date-night hero.

-

FAIR AND SQUARE

Post-Fair Brings Equitability to Santa MonicaLast week, during Los Angeles Art Week, I saw James Franco everywhere. I saw James Franco at Felix at the Hollywood Roosevelt, where the David Hockney-painted pool was closed because a man had had a heart attack inside it the day before. I saw James Franco at the Karma party at Ghengis Cohen, his trucker hat popping up behind a psychic and very beautiful astrologer. I saw James Franco at Frieze, taking in the valuable wall real estate at the sizable David Zwirner booth. But the first place I saw James Franco smile was at the inaugural Post-Fair in Santa Monica, as Theta gallery founder and director Jordan Barse took him through her exhibition of Tinseltown-themed paintings by Pictures Generation artist Nancy Dwyer. I smiled at the Post-Fair, too.

The Post-Fair, a little jewel box of a fair held at the landmark Santa Monica Post Office building, was founded by Mid-City gallerist Chris Sharp, a dealer with excellent taste and an aptronym for a surname. He decided to start his own fair for a simple reason: Frieze, where the price of a small booth starts at $35,000, is just too expensive. Participating in that fair, or even its somewhat less costly alternative, Felix, can knock out an emerging gallery like Sharp’s, whose business is four years old. He aimed for something more equitable than the established fairs, splitting the cost of renting the post office between 26 galleries (all showing single-artist presentations) for a flat rate of $6,000 each.

“We’re in a moment where things are so difficult,” he says. “Survival feels so precarious and the market’s so weak, so I just wanted to create something where participating in it wasn’t an existential threat to the gallery. Because a lot of the time, when you’re doing these big fairs it’s make or break, just because the costs are so high.”

“To use Marxist terminology,” he says, chuckling, “we’re seizing the means of production.” The name really works.

Image by Artillery staff. Sharp’s fellow gallerists met the idea with enthusiasm. He invited galleries ranging from decades-old, established institutions like Sprüth Magers and PPOW, to far younger galleries, like the Dimes Square-adjacent King’s Leap, and CASTLE, which opened in a Hancock Park apartment less than two years ago. Instead of constructing conventional booths, each gallery received equitable wall space, lending the fair the feeling of a group show. The 1938 building, sun-soaked with Art Deco moldings and worn stone, was a pleasure to move through, especially in comparison to the claustrophobic convention center at the Santa Monica Airport. Numerous guests commented on how nice the space smelled, like fresh cut wood.

“It’s a really beautiful space, and the flow is nice and pleasant,” says Barse. “I love the scale of it. It just feels very manageable, whereas many fairs can feel very overwhelming and exhausting, with layouts that make you feel trapped. But I think that people flow through quite naturally here without feeling pressured or rushed. You’re engaging visitors more easily, and they have time to stop and chat about the art.”

Eden Deering, director of PPOW—which showed Harry Gould Harvey IV’s storybook-like, eerie work—described the Post-Fair as “refreshingly human.”

“It avoided the often transactional feel of white-walled booths,” she says. “Instead, it offered a sense of discovery and connection.”

Between the low costs and minimal construction, Sharp purposefully created an environment where there’s “a lot less pressure” to make sales, enabling exhibitors to take more aesthetic risk. He opted to show work by the late German-Iraqi sculptor Lin May Saeed, centering a piece depicting a wide-eyed, nervous doe. Sharp says that, despite Saeed’s renown in Europe, she has no market in the United States, and he relished the opportunity to bring her to a wider audience.

“I actually really like art fairs,” he says. “A lot of people complain about them, but one of their great virtues is you get a lot of people in front of your work. At my gallery, I’m lucky if I get 300 people to visit the show over the course of the entire show. You do an art fair, and you get thousands of people. I mean, not like everyone’s going to look, but you’re still getting this really high volume of exposure for your artists. So this fair is a perfect context to be able to show work by Lin May Saeed, where if we don’t sell anything, it’s not a big deal.”

Chris Sharp. Photo by Artillery Staff. Sharp expected some amount of blowback from the powers that be at Frieze. But the devastating Los Angeles wildfires changed things. “My fair feels like it’s essentially somehow critical of the status quo, but the fires and the aftermath kind of created this really nice and unexpected solidarity among the entire art community,” he says. In 2025, attending LA Art Week was not just an excuse to take pictures of one’s friends’ art and enjoy a complimentary champagne in a lounge sponsored by a Swiss bank—instead, it became a way to both offer real, needed support to the city’s artists and art workers, and to blow off steam and have fun. People actually danced (and made out on the dance floor) at the Hop Louie party. Everyone needed to breathe, maybe even the James Francos of the world.

CASTLE founder Harley Wertheimer, who exhibited paintings by Victor Boullet at the Post-Fair (my favorite was of a charming little owl with red-rimmed eyes), says we need people coming to LA in the wake of such tragedy. “I don’t even think it’s a purely financial thing,” he says. “It’s also an energy thing. It’s a beautiful city filled with beautiful, hardworking people who work in the arts, and their work should be seen.”

Post-Fair’s spirit of experimentation leaked over into Art Week as a whole. The New York-based Uhaul Gallery, which shows work in a moving van, parked outside the Santa Monica Post Office after getting ejected from Frieze. There was an inflatable tube man, like the kind they display outside car dealerships, waving around atop the van, by artist Sam Keller. He was rendered in the stars and stripes of the American flag, with an erect, inflatable tube penis flopping in the breeze. He made me happy.

-

LESS THAN ZERO

On Risk and Art in Los AngelesI’m at a bar in Palmdale and it’s nearly empty. From where I am sitting, I can see two men playing chess. Or, rather, they’re not really playing—they’re afraid to make a move. It’s Pawn to E4, followed by the all-too-familiar analysis paralysis: finger steadies the piece, eyes tighten, neck cranes and turtles to check for danger, and then…Pawn back to E2. Let’s start again. Every move never happens, just like this.

It’s a riskless game, and stagnant, and it reminds me of the state of the arts in Los Angeles.

Since forever, LA has been about risk. We tell big stories on big screens about success against all odds. Our stars come from nowhere, move here on hayseed budgets with bindles full of aspiration and little else. Our freeways host the most spine-shearing car chases in the world; our sports are considered extreme, our politics radical, our drugs potent; and, recently, we’ve been reminded that we all essentially live in one big pile of kindling that’s oh by the way right along the San Andreas Fault.

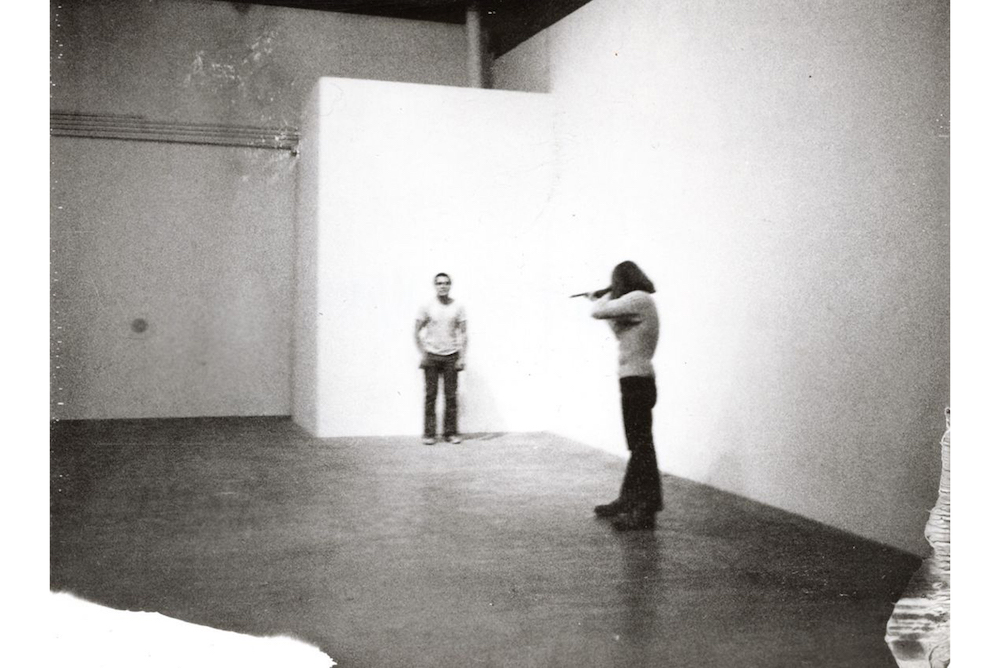

Chris Burden, Shoot, 1971, at F Space in Los Angeles. LA’s art is no different, at least historically. In the ’70s—amid Nixon, Vietnam, assassinations, moon landings and riots—Chris Burden had himself shot and crucified (Shoot, 1971; Trans-Fixed, 1974), Barbara T. Smith had sex with three men in one performance (Feed Me, 1973), Pippa Garner flipped a Chevy’s chassis and drove it backwards across the Golden Gate Bridge (Backwards Car, 1974), and Paul McCarthy fucked a bunch of raw hamburger meat with a hotdog up his ass, and videotaped it for everyone to see (Sailor’s Meat (Sailor’s Delight), 1975). At the same time, CalArts, as we know it, opened, and counted among its faculty one artist who burned all his paintings (John Baldessari), one who called twenty minutes of blank film a finished film (Nam June Paik), and another who believed that artists should stop making art altogether (Allan Kaprow). The history of LA art, of course, is far more complex and diverse, but this is the genesis of its popular spirit, one that plumbs the depths of taboo and skewers convention.

That spirit, however, has faded. LA art is staid now. Maybe all art is. And it sort of makes sense, too. Up until very recently the art market has been healthy, even booming. But memories of 2008’s Great Recession linger in the rearview, so despite the upswing, a tendency toward stability, toward the sure thing, is understandable. It’s also unfortunate because the sure thing is categorically anti-risk. It calcifies convention: Institutions get comfortable, galleries follow, and artists end up having to choose between satisfying a mandate to exhibit or not exhibiting at all. To rock the boat is to threaten the art world’s prized equilibrium, so little-by-little all movements of any kind are discouraged, until the boat stops moving altogether and things become inert.

Take Jeffrey Deitch’s recent “Post Human” show, for example, a reprise of his 1992 show of the same name. One look around and it’s clear that the most challenging, insurgent works in the gallery—let alone the city—were made yearsby artists currently in their 80s, or who are now even dead. I’m thinking of McCarthy’s Garden (1991–2), of course, Charles Ray’s Family Romance (1993), and Cady Noland’s Rotten Cop (1988), but there are others. Even some of the more striking contemporary work—like Josh Kline’s Aspirational Foreclosure (Matthew / Mortgage Loan Officer) (2016) and Ivana Bašić’s I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms #2 (2017)—“shocks” in the same way that American Psycho or Marilyn Manson shocks, which is to say, only to viewers still living in the 1990s, who haven’t discovered the internet yet. In other words, the best new works here are old hat… pastiche, even.

And that’s the good stuff! Most art shows in LA are about as avant-garde as a corporate happy hour, except without the funny business from Kyle in accounting. Our schools, too, are factories of modest work—CalArts and UCLA, yes, you—training artists to avoid risk, or at least render it invisible, by using concepts like opacity, camouflage and misdirection. At one point, these approaches were an effective counter to the art world’s commodification of difference. The many social justice movements of the 2010s spawned a market that valued marginality so long as it was legible in the work. That is, artists were encouraged to prove it—their identity, their culture, their trauma—and to be explicit enough about it for it to sell, which quickened a roundabout march toward reduction and stereotype. An opaque approach then, in theory, protected the artist’s subjectivity from the capital forces seeking to exploit it. However, it has evolved. More recently, opacity has been used as a tool to avoid rocking the proverbial boat, regardless of identity: Say what you want to say, but make it illegible, and position it juuuuust right. At least, artists can then maintain some degree of integrity without sacrificing career advancement. However useful, these strategies aren’t pioneering or revolutionary: David Hammons, for one, made an entire career out of them, starting in the ‘70s.