Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Liz Goldner

-

OUTSIDE LA: Junior Art Exhibition

Laguna Beach Festival of ArtsOne of the most popular shows at the Laguna Beach Festival of Arts is the “Junior Art Exhibition,” featuring 400 art pieces by 200 Orange County students from kindergarten through grade 12. The show reveals the vast variety of artistic influences that students draw from today, including figurative, cubist, abstract, and digital styles.

The illustrations, paintings, collages and photos, exhibited salon-style, highlight the wide array of young people’s often-joyous creativity. Portraits reveal faces that are thoughtful, serious, and occasionally sad. Dragons, skeletons, landscapes and animals are popular. And a few dozen well-crafted sculptures made of ceramics, papier mâché and other materials depict busts, animals, masks, jars, vases, a roller skate, a cake, a rooster and a giraffe head.

Among the portraits is Expressively Frida, a clever likeness of Frida Kahlo by Ginesis Vera (Grade 7). Persian Coca by Yekta Chinichian (Grade 12) depicts a traditionally dressed Middle Eastern woman selling Coca-Cola in an elaborately detailed setting. Self Portrait Picasso Style by Emie An (Grade 1) shows a girl with an askew nose, oddly shaped eyes, a heart tattoo, and multi-colored hair—all in Picasso’s cubist style. Remy Chiu (Grade 5) pays homage to the artist in Picasso Inspired Face, by cleverly using cardboard to achieve three-dimensionality.

Dragon Snake by Rosie Hooper (Grade 5)—one of several dragon artworks on view—shows an intricate, scary dragon face extending from a snake body. Tristan De Villiers’ (Grade 5) Vibrant Dragon Mosaic depicts a dragon’s purple face with eyes blazing, fangs growing from its cheeks, extended ears and antlers. A gleeful dragon with a long red tongue and multi-colored feathers is the focus of Jayleen Olivares’ (Grade 9) Brown Pride. And Purple Dragon’s Eye by Savannah Kelly (Grade 4) features one large expressive eye of a dragon staring intently at viewers.

A compelling skeleton in this exhibition is Dressed to Express by Ivy Olivas (Grade 11). Its deft penmanship reveals four elaborately dressed skeletons, looking cool while lounging, with their bones and clothing demarcated against a vortex background. Traveler by Apocalipsis Camacho (Grade 7) is a humorous rendering of a skeleton, casually dressed in a scarf and sombrero, holding onto a bottle while roaming in a field— perhaps heading to a better land.

One of the most attractive works in this exhibition is Railway to Hana by An Do (Grade 10). It depicts a colorful train ambling down a narrow street with clotheslines above and open windows that reveal colorfully decorated apartments. A particularly cute drawing, Cat with Fish Bowl by Hazel Baron (Grade 1), shows a large yellow cat reaching for three fish. Perhaps one of the cleverest works here is the digitally designed Robots by Sarah Hu (Grade 12), which depicts two robots standing in a space station, the taller one holding onto a pitchfork, mimicking Grant Wood’s often copied painting, “American Gothic.” And the cubist-inspired Piece by Piece, created by fourth and fifth graders, overlooks the entire exhibition with a fierce lion with wildly unkempt fur, one green and one blue eye.

The Junior Art Exhibition promotes art education and self-expression while offering young artists the opportunity to display their talents to a wide audience. It further confirms the indispensable role and importance of art instruction today and of its dedicated art teachers.

-

CALIFORNIA GOLD

Hilbert Museum Expands its Space and CollectionMillard Sheets’ glass mural Pleasures Along the Beach (1969) adorns the façade of the Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University in Orange, CA. Its brightly colored California scene, portraying sunbathers, birds and sailboats, beckons visitors to the newly expanded 22,000-square-foot museum.

While the Hilbert Museum has many art pieces on display and in its collection, museum co-founder Mark Hilbert is always “on the hunt” for new works. Recent acquisitions include paintings by Chicano artist Alfredo Ramos Martínez, early drawings by Richard Diebenkorn and Diego Rivera and a 2012 drawing of a woman wearing a Luchadora (Mexican wrestler’s) mask by Chicana artist Judithe Hernández, who addresses colonialism and sexism in her work.

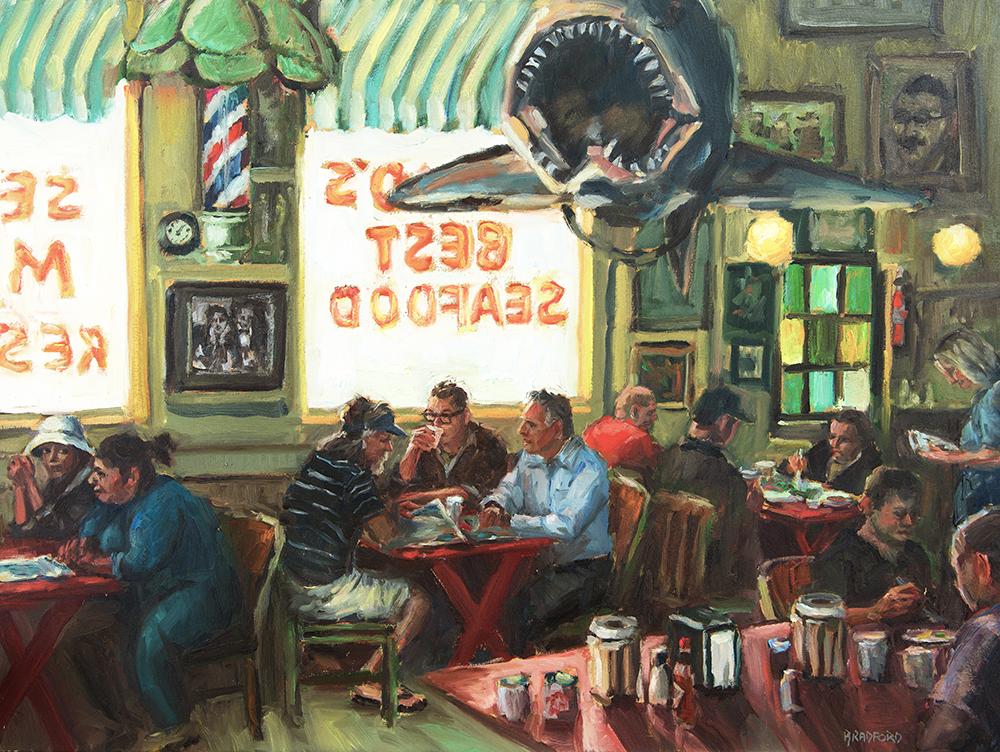

Within the museum’s two buildings and 26 galleries, 300 treasures from the permanent collection and temporary exhibitions are housed, many of them visual narratives of California life from the late 19th century to the present. “There are so many gems of storytelling here,” says Hilbert, admiring Bradford Salamon’s 2016 painting Monday Night at the Crab Cooker, which captures Hilbert, curator Gordon McClelland and the artist enjoying a meal at a popular local restaurant. “The stories depicted in the California scene paintings are about California life, about the artists and the lives they led, and feature people in towns, cities, harbors, houses and ranches. They are inspired by such American scene painters as Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood and Edward Hopper.”

Fletcher Martin, Bucolic, 1938. The museum’s permanent collection documents 150 years of California art and life. One of the earliest paintings, Looking up Broadway in Los Angeles (1913) by John Robson, provides a look at Downtown LA with “Red Car” electric trains, automobiles, fashionably dressed people and movie palaces. Frank Ashley’s The Barefoot Sixties (1968) features hippies in a San Francisco cafe, and Frank Romero’s Closing of Whittier Blvd. (1990) depicts a feud between police and the local lowriders during the 1970s in East LA. Other highlights on display include Fletcher Martin’s Bucolic (1938), which shows a quiet, reflective couple seated on the ground, its style evoking Mexican muralism, and Phil Dike’s Sunday Afternoon in the Plaza de Los Angeles (1939), a lavish painting of people enjoying themselves in a downtown park, just before World War II.

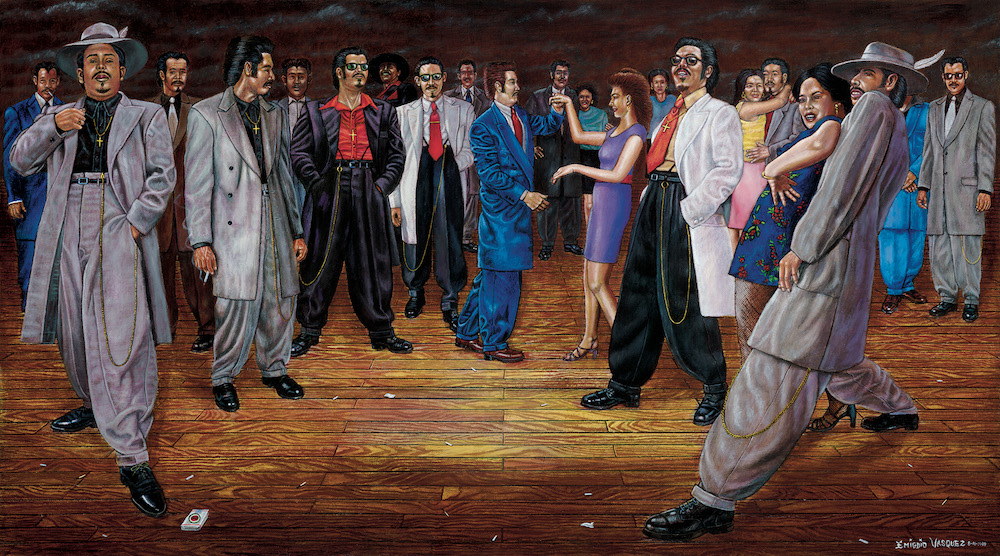

Three inaugural exhibitions feature scenes and styles prevalent in 20th-century California. The Millard Sheets display comprises 40 of his colorful works, another gallery of Emigdio Vasquez’s work presents mid-century social realism art of Orange County Chicano life, while “A Matter of Style: Modernism in California Art” showcases 50 abstract and semi-abstract works by a variety of artists, including Helen Lundeberg and Stanton Macdonald-Wright.

Hilbert and his wife Janet, a co-founder, have been collecting California art for more than three decades. When they purchased a 1950 watercolor in 1992, they didn’t realize that it would be the genesis of a major museum. They fell in love with the landscape and began studying the painting’s origins, meeting with art historians, and traveling to Europe to understand the styles and forms of work by the Old Masters. With their new passion for art, the Hilberts acquired additional California scene paintings and began acquiring narrative art with a figurative California style, becoming the defining feature of the future Hilbert Museum.

Frank Romero, Closing of Whittier Blvd., 1990. As their collection grew and museums around the country began borrowing their paintings, the Hilberts decided to create their own museum. They approached Chapman University in 2014, proposing to donate $3 million in paintings and $3 million for the museum building. The original 7,500-square-foot institution opened in 2016 in Old Towne, Orange Historic District.

Dedicated to engaging and inspiring visitors of all ages, and advancing appreciation of California through art, the Hilbert Collection has grown to more than 5,000 works, including Disney production art and paintings by Mary Blair, Rex Brandt, Sandow Birk, David Hockney and numerous others.

With the museum’s collection growing and thousands of visitors every month, the Hilberts realized three years ago expansion was a must. After two years of design and construction, and a grand opening this past February, visitors from SoCal and beyond are now charmed by the venue’s many illuminating scenes of our Golden State in the refurbished museum.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: “Before You Now”

Riverside Art Museum“Before You Now” features work by 56 artists who employ photography, prints, drawings, installations and video to depict themselves, their identities and, especially, their artistic perspectives. Rather than creating traditional self-portraits, these symbolic, conceptual and occasionally humorous images express the artists’ deeper personas.

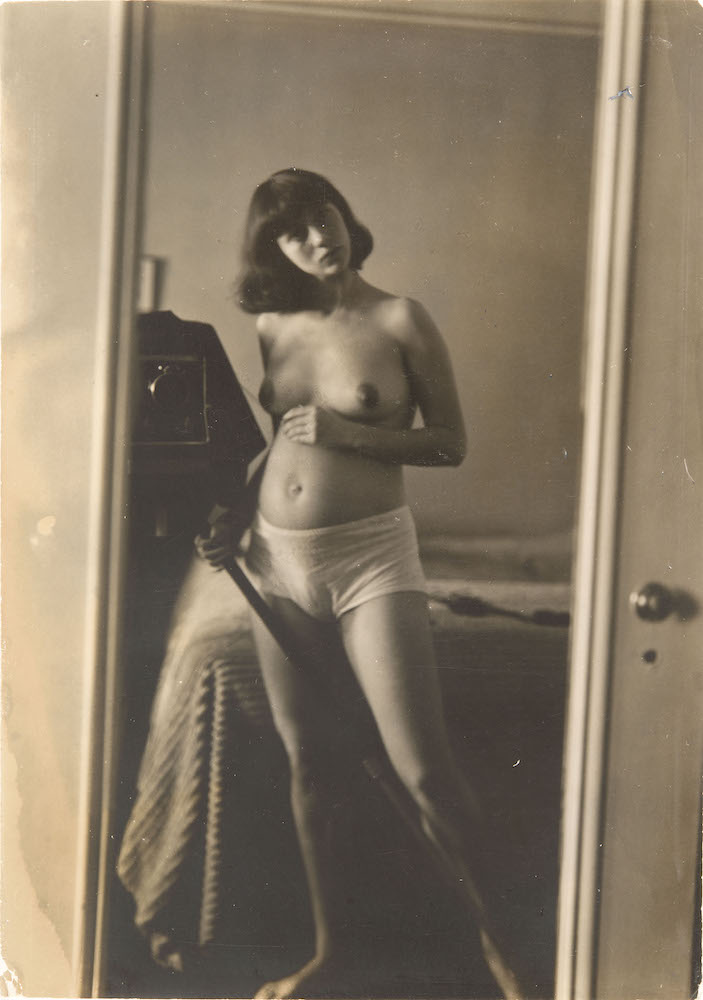

The artists whose self-portraits are displayed range from the relatively unknown to superstars. The latter include Diane Arbus, whose photograph Self-portrait in mirror (1945), taken when she was 22, beautiful and shapely, is a nude depiction of her with a soulful expression, holding onto a large camera. The photo reflects the artist’s lifetime of documentary-style work, in which she confronted and exposed the deeper nature of her subjects, many of them living complicated lives, as Arbus did.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self-Portrait (1988) appears as a traditional self-portrait. The backstory is that it was shot by his brother Edward, just a few months before he died from AIDS-related complications, as he was too weak to photograph himself. A closer look at the image, which depicts the artist’s head floating in a sea of black as he clutches onto a cane, is perhaps prescient of the fate awaiting him. While Mapplethorpe did not shoot the photo, he apparently directed it, as it reveals his expertise in creating black-and-white celebrity pictures—one of his artistic specialties.

June Wayne, who founded the Tamarind Lithography Workshop (first in Los Angeles, later in Albuquerque), created the lithograph Noon Self (1973). The semi-abstract image depicts her lightly illuminated face floating in an ethereal background, with her hair like a halo—surprising details for the normally well-groomed Wayne. With her eyes and brows darkened, the self-portrait combines the artist’s intense creativity—illustrated by her graceful face, hair, and background—with her darker eyes representing her grounded, no-nonsense approach to her lithography business.

Roger Shimomura, Kansas Samurai, 2004. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of artist. © Roger Shimomura. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA Included, too, is the lithograph Kansas Samurai (2004) by the lesser-known Japanese American Roger Shimomura, who’s still alive at 84 years old. The traditional-styled artwork presents a fierce sword-wielding samurai with eyes blazing and drawings of 1950s-era comic book characters in the background. Shimomura and his family relocated to a Japanese internment camp during World War II when he was only two years old. Facing racial and cultural stereotyping throughout his life and being an avid collector of American comic books who later taught art at the ethnically myopic University of Kansas, Shimomura drew on his life experiences to create Kansas Samurai. The Japanese wood-block style print of himself in traditional samurai costume reflects the intense, proactive attitude he assumed to succeed in an often-hostile world.

Other artists whose figurative, abstract, and conceptual self-portraits grace this exhibition include Nancy Buchanan, Marisol, Ed Moses, Bruce Nauman, Catherine Opie, Man Ray, Cindy Sherman, Patssi Valdez and Andy Warhol.

“Before You Now” (with work loaned by the L.A. County Museum of Art) reveals the artists’ diversity of perspectives and approaches to life and art, as few other group exhibitions can. The catalog explains, “The exhibition aims to broaden the topic to include those whose imagery leans into autobiographical narratives rather than functioning as traditional self-portraiture.”

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Material Recovery

Angel’s Gate Cultural Center“Material Recovery” combines printmaking with assemblage, collage and sculpture to illustrate the iconography of the Port of Los Angeles in San Pedro, along with images suggesting the waste left there by the shipping industry. The exhibition of 81 pieces by 31 artists—using recycled materials—eclipses the “art for art’s sake” concept; yet, important aesthetic aspects are imbued throughout. The show was created by Lynk Collective, a group of SoCal artists who collaborate on projects and installations, employing printmaking techniques.

The collagraph, relief, monoprint, drypoint and etching prints, in figurative to abstract styles, depict the nearby industrial forms, along with natural and biomorphic images. Curated by Christina Yasmin Fesmire and Jared Millar, the pieces are printed onto reclaimed cardboard, paper, leftover chipboard, plastics, old compact discs, thrift store fabric and wood. The printed pieces, along with complementary sculptures, all created in 2023, present both the benefits and spoils of our industrial society.

The show’s centerpiece is the installation, Container, by Alexandra Chiara, Christina Yasmin Fesmire, Nguyen Ly, Diane McLeod, Jared Millar, William Myers, Olga Ryabtsova Paula Voss and Zana Zupur. The mosaic-style Container is composed of 32 collaged and printed panels on found paper, depicting the vistas, viewed from the nearby Gerald Desmond and Vincent Thomas Bridges, spanning the passageway from Long Beach to San Pedro. At 96 by 192 inches, the piece mirrors the size and shape of the metal shipping containers in the harbor, as seen from those bridges. While visually referencing cranes, bridges, machinery, graffiti, local fauna and flora, the work evokes the maritime world of longshoremen.

The Discard Project involves exchanged prints that original artists considered to be unfinished or unsuccessful. Their successors transformed the donated prints into stunningly creative work. Under the Big Top by Tracy Loreque Skinner and Paula Voss features a semi-abstract, jubilant circus performer on a prancing horse. Primavera by Alexandra Chiara, Elisabeth Beck and Bill Jaros, illustrating a blue-faced woman in profile with flowers bedecking her head and adorning her bodice, suggests the ambiance of spring.

Diane McLeod, Yeansoo Aum, Elisabeth Beck, Andra Broekelschen, Alexandra Chiara, Christina Yasmin Fesmire, Karen Fiorito, Bill Jaros, Nguyen Ly, Laura Shapiro, Tracy Loreque Skinner, Paula Voss, Zana Zupur, Discard Project, 2023. Also in the show is Laura Shapiro’s Precarious Kinship, an aesthetically attractive assemblage work, consisting of numerous unraveled paper bag handles. These opened handles become the shapes of feathers, corn husks or palm fronds, and are printed in a variety of colors. The resulting piece, with the handles carefully stitched together with embroidery thread, is both fragile and evocative of indigenous art.

This exhibition also includes wooden sculptures referencing the discarded and reclaimed wood polluting the San Pedro Harbor. Among the most majestic is Francisco Rogido’s How Often/Question and Doubt Whether That Is Really Me, a bust of a man’s head, reminiscent of primitive sculptures. Rogido explains that the piece mirrors his emotional journeys of having moved among three countries, three cultures and three concepts of life. Two drypoint, hand-printed relief prints, Head I & II, installed behind the sculpture, mirror the piece and enhance it.

“Material Recovery” expresses an ecologically conscious viewpoint by a diverse group of printmakers who live and work in SoCal. By employing discarded materials, their work conveys their artistic perspective that we all inhabit a shared earth that we must protect.

-

MALKA GERMANIA

Yael Bartana’s Jungian Journey Into the Past and PresentIn an age when so much gratuitous violence pervades our screens, the three-channel film Malka Germania presents a gentle Jungian perspective on the effects of the Holocaust on today’s German citizens. The film alludes to collective trauma about war and subjugation, while transforming that trauma into manna.

Malka Germania (Queen Germania in Hebrew), created by Israeli native/Berlin resident Yael Bartana, features the elegantly androgynous Malka (Gala Moody) moving slowly through Berlin while attired in a long, hooded robe. She dominates the city—portrayed in the film as the locus of Germany’s draconian past—and observes people going about their lives, including soldiers in the Israel Defense Forces, Hitler Youth in training, beautiful female dancers and an organ grinder. The three-channel process provides a visceral look into the German people’s awareness of their collective history. As the channels segue onward, the film encourages Berlin residents—and us—to envision images of persecution and power.

Other players in the film include fair-haired beachgoers relaxing, playing and riding in boats, until the noise of helicopters disrupts their false sense of well-being. The awareness of a warmongering past is emphasized with sounds of marching soldiers, traffic noise, church bells and barking dogs.

Installation view of “Yael Bartana: Malka Germania” at Contemporary Arts Center Gallery, UC Irvine, 2022. Photo: Yubo Dong. A concluding scene features a computer-generated image of an imperial Nazi “Hall of the People” rising from a lake that evokes Albert Speer’s proposed design to celebrate Germany’s World War II victory. It also references the lost city of Atlantis, a fictional parable about the dire consequences of corruption and arrogance. The film closes as hordes of German citizens walk wearily along the railroad tracks, leaving Berlin, as Malka looks on approvingly from a separate channel.

While portraying the ambiguities of the contemporary German- Jewish experience, the film merges the past with the present. As a Jewish woman, my dreams, memories and current perspectives are often framed by an awareness of the persecutions and fears of my ancestors, who lived through life-threatening pogroms, the repercussions of which can be felt with my relatives today.

Malka Germania has compelled me to embark on a Jungian journey of examining my legacy as metaphor for and reflection of the larger world’s tendency toward war and domination—and to view that legacy as a stimulus and muse for creativity, as Bartana does in this important film.

-

Yolanda González

Museum of Latin American ArtThe quality and diversity of the work of Yolanda González—a painter, illustrator, printmaker and ceramic sculptor—makes a solo installation of her work long overdue. This current exhibition, with nearly a 100 pieces from the career of the 59-year-old LA–based Chicana artist, does not disappoint. Embracing figurative and abstract styles, she often bases her portraits on herself, with clear inspiration from German Expressionism and Chicano art.

Following studies in studio art at Pasadena’s Art Center College, which she attended on scholarship, and a fellowship residency in Japan in 1994, González started a series of mostly monochromatic prints and paintings that depict dark bodies and bold gestural strokes. With titles such as Reaching for Sanity, Crossroads and Spiral, these works feature swirling shapes, surrounding staring eyes and faces that peer out at the world. Some of the pieces feature bright colors, like Metamorphosis in Red, which conveys passion with its shapes, reminiscent of hearts, and in the more somber Blue Conga, with its sideways face and skewed breasts. Continuing this series of two dozen works for three years, González describes it as an effort “to put a face on the monsters in our psyches, and to see the beauty in them.”

In 2020, González began her “Metamorphosis II” series in honor of her mother who had recently passed away. These darker pieces have such titles as With Eyes Closed…Nine Spheres and Through the Veil…Six Spheres. More figurative than work from her earlier ”Metamorphosis” series, they contain detailed faces and female bodies, often conveying soulfulness and even despair with their harmonious arrangements.

Yolanda Gonzalez, Sueno, En la Espaldas de Nuestros Antepasados, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Latin American Art. The artist’s acrylic-on-canvas portraits in the second gallery include Dream of the Artist (2013), which depicts three stylishly clothed and made-up women, with one posing for a portrait, and a second woman facing her while working at an easel. Both women, with dignified and sincere expressions, have almost identical facial features. Self Portrait with Scaramouch (1999) shows González attending a party in Italy, while elegantly attired in a black cape and a mask with the long fake nose typically worn by doctors and aristocrats during the Bubonic Plague. This painting, among many other vibrant works in the second gallery, is the artist’s most humorous piece in the show.

With features similar to those in her portraits, González’ ceramic sculptures in both galleries are finely wrought busts of women. Several watercolor and pencil works, including Portrait of Emily on Green (2022) and Dreams about you (2020), are portrayals of nudes who brazenly reveal their breasts to the viewers. The few watercolors of men in the exhibition are far less salacious and more modest.

González’ three acrylic still lifes, The Sweet Love of Red, Still Life in Blue and Still Life Pink Tulips, burst with profusions of colorful flowers in full bloom.

Emphasizing González’ expansive art practice, this exhibition showcases pieces that manifest her grief, humor and love of elegance.

-

Luis C. Garza

Riverside Art Museum[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”] [et_pb_row admin_label=”row”] [et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]Luis Garza was a dedicated artist and visionary who helped advance Chicano culture and activism in the 1960s and 70s through his compassionate photos. Born in 1943 in the South Bronx, he moved to Los Angeles in 1965, searching for a lifestyle more amenable to his Mexican-American heritage.

Two years later, the Chicano populace on LA’s east side were discovering their Chicanismo, their newfound sense of ethnic and cultural pride, while organizing for civil and political rights. Garza identified with the movement, calling it his razon de ser. He began photographing the civil rights movement for the socially conscious Mexican-American newspaper (later magazine) La Raza. As he documented the activists his artistic eye empowered him to also capture the faces and gestures of the local citizens—the workers, shoppers, school children and street preachers—as they pushed toward greater equality.

Garza was also a film and theater arts student at UCLA, then a producer/director for Emmy-award winning documentaries and primetime shows and for films. (He has subsequently curated many Chicano-themed productions and exhibitions, including La Raza for the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, 2017 to 2018.)

Luis C. Garza, Sueño, 1972. Courtesy of the artist. The Other Side of Memory is notable for its documentation of Garza’s East Los Angeles community in the1960s to 70s, along with photos of his South Bronx neighborhood and women demonstrating in New York back then, as he visited his hometown frequently. Also on view are images from Budapest’s 1971 World Peace Council where Garza met muralist David Siqueiros. The show comprises 66 black-and-white silver gelatin prints, brings up memories from 50-plus years ago and calls to mind the work of Chicano artists Gilbert “Magu” Luján, Frank Romero and others.

Exhibition curator Armando Durón, a Chicano art collector, selected and paired many photos to conjure up these memories, while encouraging viewers to construct from them their own narratives. In Raza Gothic (1974) an old, poorly dressed Chicano couple, evoking Grant Wood’s American Gothic, is paired with Joyeria Mexicana (1979). The latter shows a younger, well-dressed, coiffed and bejeweled Angeleno couple—the man wearing an elegant three-piece suit, heels and rings. The woman beside him dons a flowing, printed dress and a fashionable blond shag hairdo.

The equally fashionable Uptown Girl (1968) in New York displays a young mod Latino woman wearing a mini-skirt, boots and hairdo adorned with a scarf, staring pensively into the distance. Soledad (1974) from LA, depicts an old woman with a deeply lined face, also wearing a scarf, staring into the distance. While the girl looks hopeful, the old lady’s face reveals hopelessness.

Perhaps the most dramatic pairing in the exhibition is Feminestrations (1970) in which a crowd of women in New York march for their feminist rights, alongside Junto (1971) which depicts Chicano teenagers marching for freedom and equality in Los Angeles; it recalls the National Chicano Moratorium demonstrations of the1970. Both photos bring to light the activist fervor throughout our country in the 1960s and 70s, an era worth remembering—and perhaps emulating.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column] [/et_pb_row] [/et_pb_section] -

OUTSIDE LA: Art & Nature

Laguna Art MuseumIn Laguna Art Museum’s 10 years of mounting its annual Art & Nature installations, a consistent theme has been the preservation of our planet. In this year’s version, the museum celebrates the beauty of nature while artfully addressing environmentalism and conservancy.

Commencing the installation, Dr. Sylvia Earle, award-winning National Geographic explorer-in-residence, oceanographer, author and lecturer, addressed museumgoers on the importance of preserving our oceans. She explained that these bodies of water are our “built-in life support system,” that “our polar ice is shrinking and it is happening on our watch,” and “it is the ocean that makes our climate what it is.” After citing statistics about our planet’s and its life forms’ ongoing devastation, she explained that artists take knowledge of the ocean today. and then reimagine a better future for all of us.

Taking Earle’s notion to heart, L.A. artist Rebeca Méndez created for Art & Nature the 360-degree, six-channel video, The Sea Around Us. Installed in the museum’s large central gallery, it examines humankind’s misdeeds regarding our oceans, while extolling their beauty. The 45-minute film with sound from an Acjachemen (Indigenous) song takes viewers into the depths of Pacific Ocean, revealing flourishing plant life, abalone fish shells and people diving. Amidst the grandeur of the ocean, there are numerous barrels that were dumped into the ocean in the mid 20th century, all containing the pesticide DDT, which still affects plant and animal life, and the overall health of our planet. Yet the video’s larger message conveys our oceans as being all-encompassing, interconnected bodies of water that are able to self-cleanse, if we are courageous enough to stop exploiting them.

Rebeca Méndez, The Sea Around Us, 2022. Courtesy of Laguna Art Museum. In an adjacent gallery, the 15-foot wide acrylic and mixed media painting The Big One (1971-1978) by Laguna Beach artist, avid scuba diver Robert Young (1936-2012) reflects in theme and majesty our expansive oceans. The painting, created with pointillist techniques, is a dense, colorful oceanscape, featuring a plethora of sea life and ocean plants. It is also a reflection of the artist’s love of the ocean, as he spent hundreds of hours throughout his life exploring the sea and its creatures.

Five Summer Stories: The Exhibition celebrates the 50th anniversary of Five Summer Stories by Laguna Beach filmmakers Jim Freeman and Greg MacGillivray. The installation describes in words and images the film, which explores the pure joy of surfing, the surf lifestyle, environmentalism and corporate greed affecting our oceans.

Stationed like a sentry at the museum’s entrance, a pyramid by L.A. based artist Kelly Berg is one of seven pyramids of different sizes that the artist created for her installation, Pyramidion. She placed six of the seven pyramids around the area surrounding Laguna Art Museum, from Main Beach to Heisler Park, from November 4 to 6. With some reflecting the magnificent rocky landscape and others contrasting with it, the pyramids provided artistic and spiritual nourishment for visitors on three sunny days.

-

Diego Rivera

SFMOMADiego Rivera’s artistic oeuvre is so connected to our collective unconscious that touring this exhibition of 150 paintings, frescoes and drawings, feels like a homecoming. The show also includes film projections of murals that the artist created in Mexico and the US and comprises the most in-depth examination of his work in over two decades. This exhibition is an artistic compendium of what Rivera referred to as life in all the Americas, as he believed that the US and Mexico had complementary histories and creative proclivities. He stated in 1931: “I mean by America, the territory included between the two ice barriers of the two poles. A fig for your barriers of wire and frontier guards.”

This magnanimous show includes romanticized depictions of indigenous people going about their daily lives, laboring, marketing, caring for children and relaxing, with many figures illustrated with rounded forms, for simplicity and accessibility. Other influences include the neutral poses and mask-like faces of pre-Hispanic Aztec art. As exhibition guest curator James Oles remarks in the catalog about the politically active artist, “Rivera would wield his art as an essential weapon—sometimes blunt, sometimes subtle or seductive—in the utopian struggle for greater racial and social equality, security, and justice.”

Diego Rivera, Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees, 1931; Stern Hall, University of California, Berkeley, gift of Rosalie M. Stern; © 2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: © The Regents of the University of California. One of the most dramatic paintings in the show, Dance in Tehuantepec (1928) features three young women wearing traditional, colorful Mexican flowing dresses and exotic jewelry, and their three male companions wearing cream-colored garb and broad sombreros. All dancers are engaged in precise choreographed steps, displaying deep concentration and the cultural importance of the dance—a testament to Rivera’s keen powers of observation. The more intimate The Flower Carrier (1935) features a man on all fours, his back burdened by an enormous basket of brightly colored flowers. A large woman behind him, presumably his wife, is helping him stand. This domestic scene conveys Rivera’s empathy for the common laborer as hero. The picturesque Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees (1931) was originally a fresco created for a private home. The piece contrasts hard-working field hands cultivating crops in an almond grove, with smiling young children enjoying the fruits of the worker’s efforts. “A lot of Rivera’s work was about reminding the viewer, who was usually elite, of the essential importance of the working class in creating society,” Oles said. “We need to be reminded again and again of the fact that prosperity rests on the backs of others, most of whom don’t enjoy that same level of fortune.”

The exhibition concludes with Rivera’s final mural, The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on the Continent, 22-feet-high by 74-feet-wide, painted in front of audiences at the 1940 Golden Gate International Exposition. Known as Pan American Unity, it is comprised of ten panels, seamlessly joined together, now installed on floor one of SFMOMA. With the Bay Area as background, people depicted include indigenous inhabitants in the U.S. and Mexico, our founding fathers, laborers, artists, architects, inventors, and even Olympic style swimmers, all celebrating our adventurous, creative spirit.

-

Bradford J. Salamon

Hilbert Museum of California ArtThe artist Bradford Salamon embraces his entire life in his artwork, from his childhood and teenage years—watching cartoons and films, surfing in SoCal, playing in bands, and engaging with friends—to the present. These experiences and influences are recollected and rendered in his current exhibition at the Hilbert Museum, a collection of 47 paintings and illustrations from the past four decades that include the artist’s friends, scenes from his life, and favored images from his childhood. These incorporate actual and fictional characters from the artist’s memory catalogue: R2-D2 from Star Wars, David Bowie, Gidget, Bob Dylan, Betty Boop, Andy Warhol,

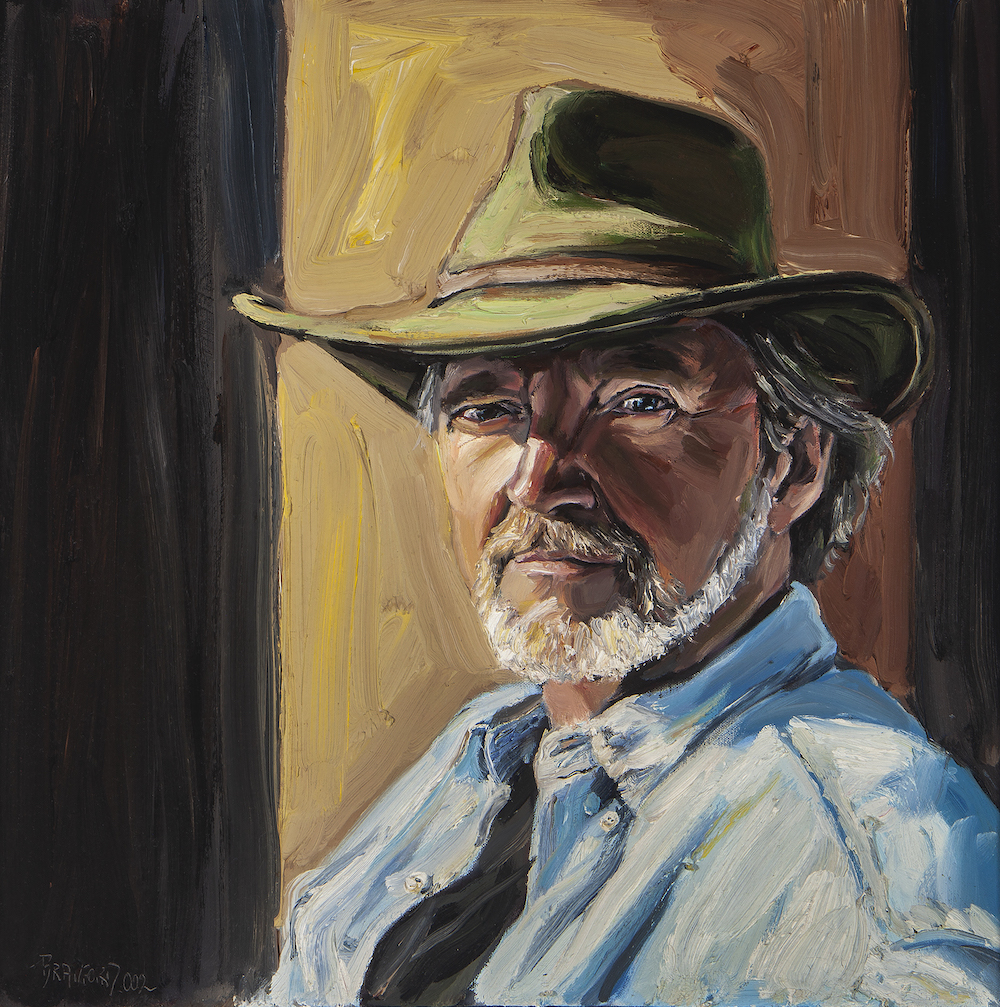

Alfred E. Neuman, and Walt Disney.Yet his painterly subjects are often his colleagues as well. A series of portraits include California artists Don Bachardy (2007), Alex Couwenberg (2012), Tony DeLap (2015), and Mark Ryden (2015) demonstrate Salamon’s intuitive approach with Couwenberg and DeLap in intense poses but Bachardy relaxing. His empathetic portrait, Clare #11 (2015) portrays Clare Dowling, daughter of artist Tom Dowling, on the cusp of her teenage years. His domestic scenes bring viewers to intimate worlds of friends and family. Expectations (2009) also features art colleagues, a pregnant Julie Perlin Lee standing proudly in her living room, while her husband David Michael Lee looks on admiringly and a bit quizzically. An art history Easter egg is revealed in the title of the book the husband is reading combined with the vessels on the sideboard behind and between the couple.

Bradford J. Salamon, Dude Descending a Staircase, 2019. Oil on canvas,The Hilbert Collection

of California Art.In another domestic scene, Sinisi Family Holiday (2017), the artist and his friends, the three Sinisi boys, stand with their mother alongside a camper scheduled for a cross-country trip. Salamon enjoyed hearing stories of their adventures when they returned home. White Rabbit (2016) illustrates the artist’s wife Kathy, his mother-in-law, and daughters Lauren, Sarah, and Monet, with the smiling Lauren spanning a doorway, while several feet above the floor. The painting (including a rabbit referencing procreation) expresses the artist’s penchant to see artistry in amusing situations. Similarly witty is one of Salamon’s most important paintings, Dude Descending a Staircase (2019), depicting a disheveled Jeff Bridges walking down a staircase.

Yet another painting suggests Salamon’s devotion to his Southern California roots, his Monday Night at the Crab Cooker (2016). This illustration of Salamon, Mark Hilbert, co-founder of the Hilbert Museum, and Gordon McClelland who curated “Forging Ahead,” enjoying a meal, is resonant with Orange County associations, as the Crab Cooker is a long favored eatery. The painting also depicts an important aspect of Salamon’s life, as the trio often meets for dinner at the storied, demolished, and resurrected Newport Beach eatery.

-

Judy Baca

Museum of Latin American ArtConsidering the breadth of the work of Judy Baca—a muralist, painter, sculptor and art activist—a comprehensive installation of her work is long past due. The current exhibition contains approximately 120 pieces from the 40-plus-year oeuvre of the LA Chicana artist. Common threads are Baca’s expressions, through her artwork, of the stories of the disenfranchised, minorities and immigrants, their strengths and long legacies, a profound connection to the earth, and especially her belief in the healing power of art.

The exhibition—curated by MOLAA Chief Curator Gabriela Urtiaga and Alessandra Moctezuma, Professor of Fine Art and Museum Studies, San Diego Mesa College—is installed in three sections. The Womanist Gallery contains female-centric drawings, paintings, sculpture, performance and photography. The Public Art Survey gallery includes murals and digital works that Baca pioneered through her Social and Public Arts Resource Center (SPARC), founded in 1976. The Great Wall of Los Angeles gallery features a floor-to-ceiling moving display of her half-mile long wall in the Tujunga Flood Control Channel, San Fernando Valley. Executed by more than 400 artists of all ages from 1974 to 1984, it depicts the history of California through the lens of women and minorities.

Begun in 1980, relegated to storage, but completed for this exhibition is Matriarchal Mural: When God Was A Woman (1980–2021), a triptych in the first gallery. Featuring 13 nude women defying a volcanic eruption, they convey the intense power of women to heal our planet, especially when bonded to each other and to the earth.

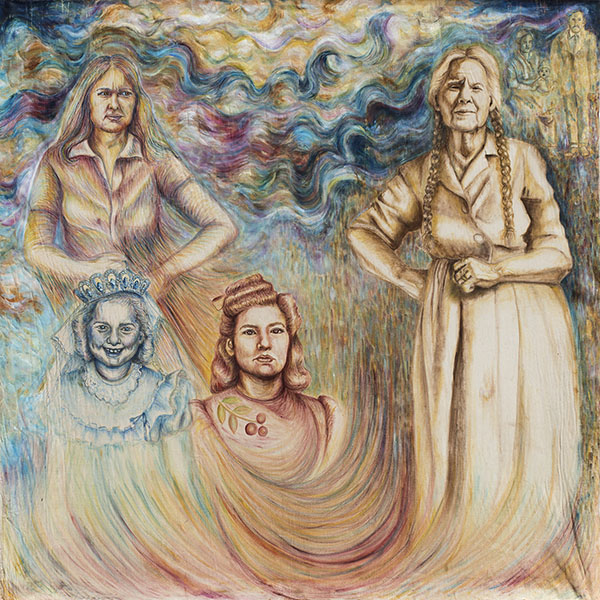

Judy Baca, La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra, California, 1996. Courtesy Museum of Latin American Art. The life-size Las Tres Marias (1976) contains a photo of a Mexican American woman, another of a Pachuca, a flashy woman portrayed by Baca, but the central panel is a mirror—inviting viewers to become the third Maria. Originally installed in LA’s Woman’s Building, it was part of an early Chicana exhibition. The compassionate Tres Generaciones (1973) is a depiction of Baca’s grandmother who raised her, her mother who supported the family, and herself—all strong, resourceful women.

Artworks in the second gallery pay homage to Chicano pioneers including César Chavez. Also displayed is Raspados Mojados (1994), a repurposed street vendor cart addressing immigration, misrepresentation, and discrimination against street vendors through photography and other media. Baca’s painted sculptural Panchos are transformed kitsch objects, originally created for tourists. The artist has instead painted each Pancho with detailed scenes of the tragedies, struggles and victories of immigrants.

The exhibition closes with Baca’s The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1984), the world’s longest mural, affirming the interconnectedness of us all. Scenes include the roles of Native Americans, Latinos, African Americans, Asian Americans and Jewish Americans in creating California. Themes explore immigration, exploitation of people and land, women’s rights, racism and gay rights. Scenes also include important 20th century European groups and individuals, including Albert Einstein. A compelling aspect of this installation is the opportunity to experience the entire wall’s interwoven stories within an hour, in a museum setting.

-

First Person

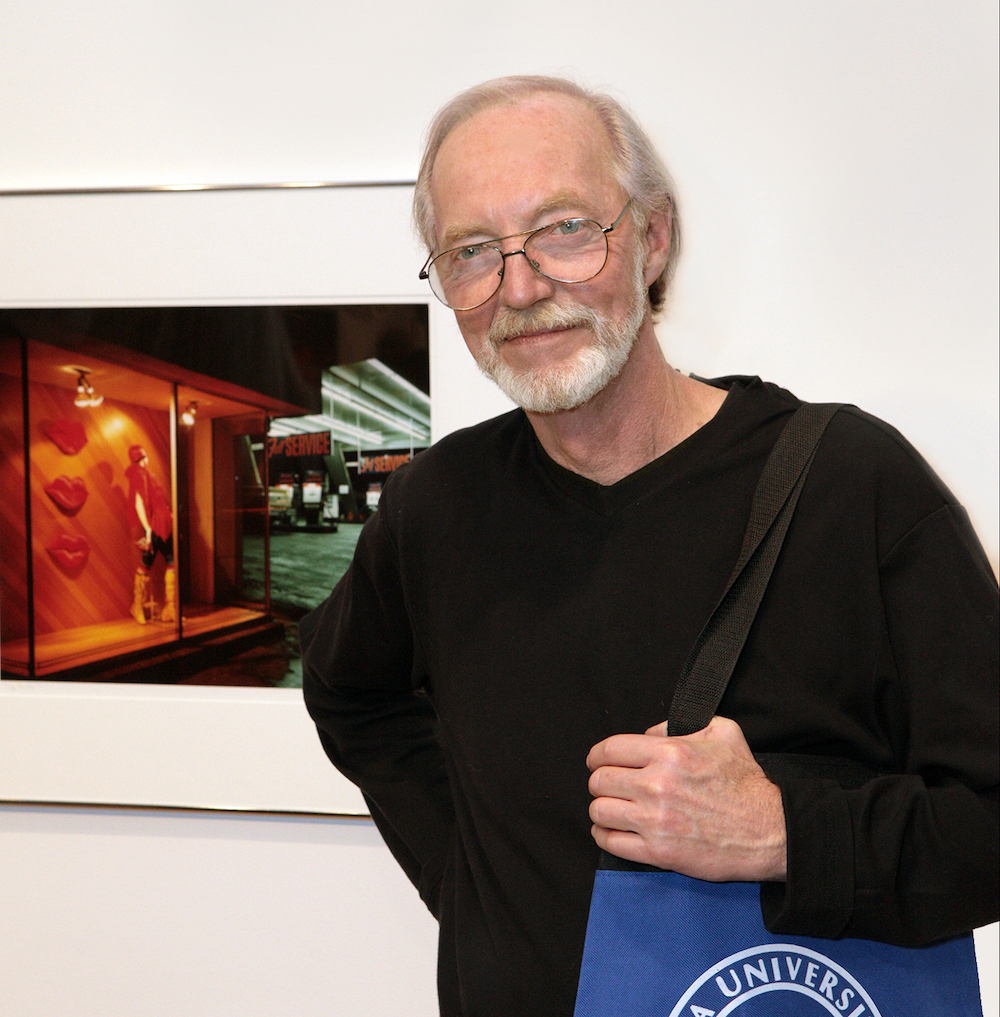

Manifesting the Pygmalion ParableI met Mark Chamberlain in March 2003, a few days after the onset of the Iraq War. I visited a gallery in Laguna Beach to write a review of his recent work chronicling the potential horrors of that war. Mark had been mounting politically charged installations for decades. I also learned that he made his living as a fine-art photographer, and that he often brought environmental perspectives into his work.

A tall slender blue-eyed blonde with longish hair, Mark was dressed casually in a frayed work shirt and sandals. His elegant manners revealed his patrician lineage. He had a profound knowledge of history and politics and possessed a razor-like focus on saving the world.

While I admired Mark’s demeanor and insights, I was more enamored with his efforts to save Laguna Beach from rampant development. His confidence and ability to accomplish daunting tasks became the magnet drawing me to him.

We became fast friends based on our mutual interests in art, politics and popular culture. Our complementary professions—he an artist/curator, myself an art and culture writer—became the undercurrent of our relationship. As a couple, we began attending art shows and openings throughout Southern California, all the while seeking advice from each other about our own work.

I moved into Mark’s Laguna Beach home in 2010 and spent several years there with him. We shared meals, watched historical programs on TV, and discussed political, social and personal events. Mark told me stories about growing up in Dubuque, Iowa, exploring the area’s topography and riding boats on the Mississippi River. I shared my memories of a Jewish childhood in the suburbs of Manhattan. We went on the road and spent a week touring his hometown of Dubuque, staying in his houseboat on the shores of the Mississippi.

Liz Goldner & Mark Chamberlain, Main Beach, Laguna Demonstration We edited each other’s writings and began collaborating on curatorial and journalistic projects. These included a book about his Laguna Canyon Project, an art concept that helped save Laguna Beach from suburban development in the 1980s. As we collaborated, we often struggled with—though eventually resolved—our differing opinions about words, phrases, descriptions and intent.

An unfortunate aspect of Mark’s confidence was his belief in his indestructibility. This attitude often drove him to stretch his body beyond its capacity, spending six weeks every summer laboring on his Mississippi houseboat. He also smoked, stubbornly insisting that the habit would not damage his body.

This lifestyle eventually caught up with him. He returned home from a grueling Mississippi trip in August 2016 with a heart infection. Soon after, he developed atrial fibrillation. While receiving numerous treatments for this condition, he continued to work intensely, and smoke.

In December 2017, Mark felt pain in his lungs and had difficulty breathing. He was told that he had terminal lung cancer. He accepted this diagnosis with quiet resignation.

For the next several months, Mark’s breathing was aided by oxygen 24/7. In March 2018, after receiving immunotherapy, his cancerous tumor broke up, filling his lungs, making breathing more difficult. He went back to the hospital where he spent his final six weeks. The book we completed earlier that year was finally published, which brightened his outlook.

Mark Chamberlain at Soka University exhibition In late April, I told Mark how much I appreciated him and how I had evolved creatively during our relationship. He responded by talking about the Pygmalion parable, in which a sculptor brings a statue he has created to life. Through his influence and encouragement, I had grown in my life, relationships and work.

Mark passed away on April 23, 2018. An artist friend later told me, “It is a gift when art can create connections with human emotions and interactions.” In fact our mutual love for art and humanity, our shared passions and the larger world had become the glue in our relationship.

Mark’s mission to save his community through his art and empathy for others were so profound that three years after his passing I still feel his presence in the expansive Laguna Canyon, which he fought so valiantly to save. His magnanimous Pygmalion-like nature continues to nurture my heart, mind and soul.

-

Marie Thibeault: Views of the Harbor

When I first saw Marie Thibeault’s hybrid landscapes that merge abstraction with representational figures, I was struck by her bold use of color and unusual iconography, in which organic and industrial shapes are combined, many inspired by the Port of Los Angeles near her home. While the underpinnings of her work suggest eco-destruction amidst the natural environment, her completed paintings become exquisite, harmonious renderings that transcend the dystopian society we live in.

A visit to Thibeault’s 100-year-old home in San Pedro entails negotiating two expansive bridges with views of ships, shipping containers, cranes and birds. This journey enables one to experience the environment that Thibeault draws inspiration from. She has for years combined and layered details of these observed images into her paintings. And while she depicts these influences semi-abstractly, she regards herself as a landscape painter.

Thibeault in her studio, photo by the artist; courtesy of the artist. When I arrived, we began by walking through the home she shares with her husband to her backyard studio. The light-infused space is filled with her paintings, drawings, color charts, books, tubes of paint, art books and computers needed to teach painting and color theory Zoom classes at Cal State Long Beach (where she has taught for three decades).

In the comfort of her sprawling studio, Thibeault discussed her early life, growing up in Baltic, Connecticut, a rural town in the state’s eastern end. “My French-Canadian parents were not artists,” she says, “but they were artistic.” She was influenced by visits to the nearby Slater Memorial Museum, and its New England landscape paintings. Viewing these masterpieces inspired her lifelong love of landscapes. “By the eighth grade, I knew I wanted to be an artist,” she said.

Thibeault attended a nearby art school where she studied drawing and painting. She also learned about the work of the masters, including Paul Cézanne, known in part for his horizontal planes. “The picture plane in his work is moving and breathing as space that moves,” she said. “I learned to paint like Cézanne.” After graduation, she attended the Rhode Island School of Design, where she received a BFA in painting, and later earned her MFA at UC Berkeley, studying with Elmer Bischoff and Joan Brown.

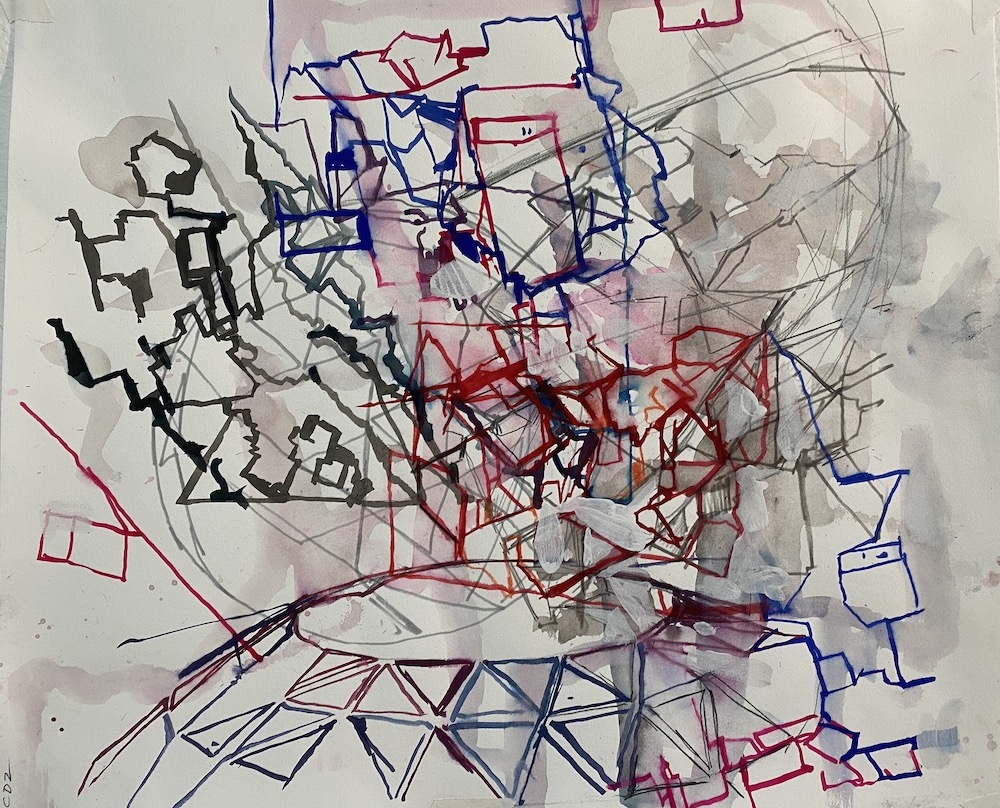

Marie Thibeault, Covid drawing group 2, 2020 She moved to San Francisco in 1979, soon afterward immersing herself in environmental movements. The initial impetus for her green consciousness was the proliferation of aerial photos of disasters in local newspapers, “especially pictures of plane and train crashes and nuclear calamities such as Three Mile Island.” She began using these aerial photos as inspiration for her paintings, and continues to do so. Among the disasters she has depicted are Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. “Destruction is the pivotal point of change,” she explained. “There is tension between instability and balance, breakdown and recovery.”

Thibeault directed my attention to specific paintings in her studio, several containing “horizon lines.” She begins each piece by drawing and stenciling abstract industrial and natural images, many of them birds, onto the canvas. Working intuitively, she expressively applies bright primary oil paint, balancing these colors with muted hues. The results are semi-abstract, harmonious landscape-influenced works that explode with color. Two such recent paintings are Shield (2017) and Moving Cities (2018), both containing deep blues, greens and black, with obscure, densely painted imagery, referencing ruination in the environment.

Marie Thibeault, Gravity’s Angel, 2019 The artist then showed me numerous drawings she began in March at the start of the lockdown. “I was blown apart by the pandemic,” she said, “and stuck at home teaching on Zoom. I was depressed and all I could do was draw, so I did three to four drawings a day.” While their shapes and forms echo those in her paintings, these drawings are more abstract and include medieval illustrations, astrological maps and ancient diagrams illustrating serpents, insects and birds. “They also use diagrammatic forms referencing global mapping and scientific charts,” she said.

Thibeault recently began saving medieval imagery from the internet and plans to employ these symbols in her future work. She explained, “With the current global pandemic and the effects of climate change, we are so much in the dark. And with many people embracing the type of superstition prevalent during the Middle Ages, these millennia-old images are particularly relevant to me.”

Sitting erect on a stool, Thibeault added, “Just as we turn to science to help us understand forces beyond our control, I am widening my view in my paintings to include a sense of global space and interrelationships, creating complex spaces with a sense of deep time, connecting the present to the past.” While her next paintings will continue to include environmental influences, they will aspire to further connect people to their surroundings and to each other, addressing what she describes as, “the tension between instability and balance.”

-

Peter Blake Gallery: : Lita Albuquerque

Lita Albuquerque’s Auric Field paintings have graced museums and galleries throughout the Southland and beyond since 1998. With each meditative piece featuring a black background, surrounding a gold or silver-leafed circle, which itself has a blue aura, the effect evokes the majesty of the larger universe that we inhabit. The artist equates the large black painterly areas of her work with the cosmos, and the circles within them with the earth.

Lita Albuquerque, “Exploded,” installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Blake Gallery. The Auric Fields evolved from the artist’s Land Art series that she first worked on in the late 1970s. This earlier series, created from what Albuquerque refers to as “pigment work” on dry lake beds, also featured circles with pigments in a variety of primary colors.

In the mid-aughts, as Albuquerque continued to create Auric Fields, she simultaneously re-explored the look and essence of her earlier Land Art, often using salt as a background for its reflectivity and pure white backgrounds.

Lita Albuquerque, “Exploded,” installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Blake Gallery. In 2016, she painted her “Embodiment” series, large scale works, with half on black backgrounds and half on white backgrounds. The circles within these paintings were again done in a variety of colors.

Expanding on this theme, Albuquerque’s current “Exploded” series, with 24 individual square paintings, all created in 2018, features six large Auric Field works in the gallery’s front room. The dramatic black backgrounds surround gold or silver circles, around which are Cerulean Blue, Cobalt Blue, Manganese Blue and Ultramarine Green auras.

Lita Albuquerque, “Exploded,” installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Blake Gallery. In the second, third and fourth room of the gallery, she experiments with a variety of background colors, including pale yellows, oranges, reds and lighter blues. Within these pieces, she again uses gold or silver leaf for the circles. In spite of this series’ dramatic title, these paintings produce a softer effect.

Albuquerque has stated her interest in creating a “vibratory” visual effect by juxtaposing pure pigments and gold leaf, noting that the invisibility of cognitive systems like mathematics and linguistics influence us at a sub-liminal level.

Perhaps these newer ethereal paintings offer an expanded understanding of our universe.

Lita Albuquerque, “Exploded,” September 15 – November 4, 2018, at Peter Blake Gallery, 435 Ocean Ave, Laguna Beach, CA 92651. peterblakegallery.com

-

Laguna Art Museum: : Tony DeLap

The sweep and scope of the Laguna Art Museum’s extensive Tony DeLap retrospective encompass several remarkable elements, including the artist’s large hybrid constructions, which feature unusual juxtapositions of shapes and materials, and his curved standing and hanging sculptures. The retrospective is divided into periods that correspond to formal shifts in the 90-year-old artist’s oeuvre, illuminating his 60 years of conceiving, conjuring and building distinctive works. While DeLap has been variously identified with the minimal, hard-edge and Light and Space movements, his pieces don’t fit neatly into any of these categories. In fact, to walk through this exhibition is to enter the mind of a master who imbues his work with magical, form defying structures.

Tony DeLap, Esoterist (1990). Acrylic on canvas with wood. 94 1/2 x 44 x 10 3/4 inches. Collection of Phyllis and John Kleinberg. Of the 80 drawings, paintings, large hybrid works and sculptures in this exhibition, several embody characteristics of what might be called “DeLapism”: a collapsing of the distinctions between painting and sculpture. These include Esoterist (1990), The Honest Ace (1996) and The Conjurian (1991). All three are composed of large geometrically shaped swaths of acrylic painted canvas, combined with free-form carved wood, the latter providing anchors and unusual counterpoints. These works, along with many others, are mounted onto abstract bases that swerve out from the wall, encouraging viewers to examine their dimensional complexity.

Tony DeLap, Lompoc (1963). Lacquer, wood, chipboard, Plexiglas, and stainless steel. 23 ¼ x 20 ¼ x 4 5/8 inches. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Robert and Naomi Lauter.

“Tony DeLap: A Retrospective,” installation view, Laguna Art Museum, 2018. Photo by Chris Bliss. DeLap’s standing square sculptures, including Mona Lisa (1962) and Lompoc (1963), display etched features and translucent finishes. Floating Lady II (1970/2017), a 108 inch beam balanced on the edges of two glass plates clamped together at a 90 degree angle, is a simple yet humorous construction, alluding to his life-long avocation of performing magic tricks.

Tony DeLap, Triple Trouble II, (1966). Heat formed acrylic plastic and lacquer. 13 x 22 1/2 x 13 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery. Also magical are long slender sculptural pieces, including Untitled (Bendo) (1972), which are balanced, seemingly precariously, on small beams. Here also are free-form sculptural pieces, Tango Tangles III and Triple Trouble II (both 1966), displaying the artist’s early experimentation with abstraction. This exhibition, magnificently curated by critic/writer/poet Peter Frank, also includes intricately designed drawings and plans for the endlessly fascinating completed pieces.

“Tony DeLap: A Retrospective,” installation view, Laguna Art Museum, 2018. Photo by Chris Bliss. “Tony DeLap: A Retrospective,” through May 28, 2018 at Laguna Art Museum, 307 Cliff Drive, Laguna Beach, CA 92651, www.lagunaartmuseum.org.

-

Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago at MOLAA

Years before the Getty’s “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA” was initiated, the Museum of Latin American Art was exploring Latin and Latino culture. Its previous 2011–12 PST, “Mex/L.A. ‘Mexican’ Modernism(s) in Los Angeles, 1930–1985,” explored the relationship between artists and supporters on both sides of the border, and included murals by José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Yet in the current PST initiative, MOLAA is reaching beyond what is commonly considered Latin or Latino art with its museum-wide “Relational Undercurrents” exhibition. Covering the Caribbean islands, the show displays work from non-Hispanic islands, including Aruba, The Bahamas, Barbados, Guadeloupe, Haiti and St. Martin, in addition to Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Curated by Tatiana Flores, a Rutgers University professor of Latino and Caribbean Studies, and Art History, the exhibition addresses the so-called boundaries separating Caribbean countries and territories, and then artistically, historically and conceptually connects these entities through nearly 200 art pieces.

The show explores the work of more than 80 artists residing in these islands in today’s post-colonial era, while revealing their frustrations and desires. With many artists drawing on a common legacy of colonialism, issues of history, identity, migration, race and ethnicity pervade their paintings, installations, sculpture, photography and videos. Their work ultimately expresses the underside of Caribbean life—a world that is light years away from the advertised version of the islands as a tropical paradise.

Scherezade Garcia, In My Floating World, Landscape of Paradise from the series Theories on Freedom, 2011, courtesy of the artist and the Lyle O. Reitzel Gallery, New York. One of the most powerful pieces in the show greets the viewer in the museum lobby. Scherezade Garcia’s In My Floating World, Landscape of Paradise (2011) consists of numerous large, blue plastic lifesavers, bound together with plastic ties, each with a JFK luggage tag. Expressing the desire for freedom through any means—by boat, plane or lifesavers—this installation epitomizes the exhibition’s recurrent theme of yearning for a better and different world.

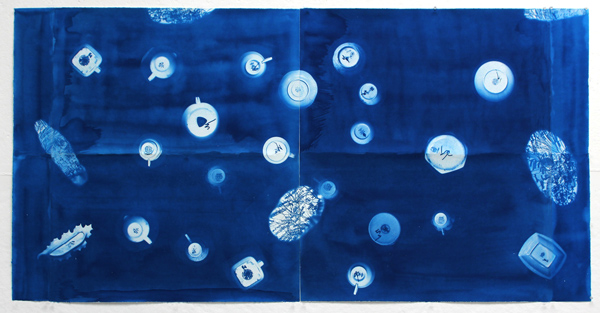

Juana Valdes, Under View of the World / El Mundo desde abajo, 2015, Courtesy of the artist. “Relational Undercurrents” is divided into four thematic sections. The “Conceptual Mappings” section includes maps and globes that re-imagine the world. Juana Valdes’ Under View of the World (2015), a cyanotype print with a deep blue background, appearing like the sea, features superimposed objects including gems, bottles and trinkets, appearing like islands. It evokes colonialism’s dependence on trade at the expense of the islanders. Firelei Báez’ gouache, ink and chine-collé on de-accessioned book pages anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River (2014–15), with female body parts superimposed over 19th-century maps, suggests the female islanders’ objectification by the traveling male patriarchy. In Ewan Atkinson’s Starman photos on light boxes (2009), the ephemeral superhero dominates urban scenes, implying the desire of the artist to overtake the environment.

The work in the “Perpetual Horizons” section focuses on the horizon, a constant presence in the islands, reminding residents of the borders that have kept them colonized and/or entrapped. Marianela Orozco’s digital print Horizons (2012) features a stretched out naked female as the horizon line, with a background of clear blue sky and puffy clouds. Yet its dreamy depiction of a female belies the deeper issue of degradation of women on the islands. Yoan Capote’s Island (The Night) (2011–12), a recreation of the ocean meeting the sky made out of fishhooks on jute on panel, is a poignant reminder of the islanders’ omnipresent relationship to the sea.

Tony Capellán, Mar invadido, 2015, found objects from the Caribbean Sea, courtesy of the artist. “Landscape Ecologies” address the environment as a place of shared ecosystems and habitats, referencing history, ecological challenges, and even disease and degeneration. One of the most alarming pieces in this section and in the exhibition is Tony Capellán’s Found objects from the Caribbean Sea (2015). This roomful of plastic cast-offs retrieved from the sea, including broken toilet seats, baskets, toys and waste from the medical industry, is organized by colors on the floor, from white to light blue to green to dark blue to black. The artistic arrangement of the detritus further emphasizes our besmirching of the environment, particularly in places bordered by the sea.

“Representational Acts” features work with political viewpoints in relation to race, gender, colonialism and more. David Bade’s My Name is Europe, Hi Europe (2014) is a large, colorful semi-abstract painting, depicting a jumble of characters; it conveys the foreboding that pervades much of this exhibition.

Antonia Wright, Suddenly We Jumped, 2014, photo by Rudy Duboue, courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles. Antonia Wright’s Suddenly We Jumped (2014), a slow-motion video of the artist smashing her nude body through a sheet of glass, evokes the Futurists’ fearless “mortal leap”—her title quotes Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who penned the Futurist Manifesto. Here, that leap seems expressive of a fervent determination to break through the subjugation of race, sex, nationalism and a centuries-old legacy of oppression. Jumped, then, viscerally embodies the mood of many of the works exhibited in “Relational Undercurrents.”