Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Janna Avner

-

Danial Nord

Danial Nord’s solo installation at the Torrance Art Museum, Cloud Nine (2018), presents translucent human-like sculptures, lit by LEDs responding to social media and video feeds. Nord fire-casted clear polycarbonate sheets into the shapes of recognizable figures hunched over their cellphones—the Businessman, Gunman, Mother, Alien, Illegal and Angel—and installed them in a darkened room set against electronic sounds. The video footage is determined by an algorithm that converts them into light, brightening each of Nord’s figures and making indissoluble the human body from its technology-driven needs.

These plastic and metal figures are also stuck with found objects and beach driftwood that reference the natural world of yesteryear. Cloud Nine depicts bodies as non-medium specific, in a Rauschenberg combine-like twist on the human body. The Angel possesses wings and floats by wires, displaying a satirical levitation. Another figure appears to either levitate or hang from the ceiling by a noose. It looks like a celestial ghost liberated by technology that grants an eternal stream of information.

In this installation, Nord muddles life-and-death distinctions, and this central complication might be the most interesting aspect of Cloud Nine: what happens when knowledge becomes over-prioritized, way above other psychological needs like face-to-face connection and real life relationships? Will our data-driven virtual world ultimately lead to the dissolution and death of what makes us human?

Danial Nord, Two-Faced Angel. Photo credit: Gene Ogami Nord’s artworks are both public and private: they reflect personal introspections on our increasing reliance on data-driven industries and the Internet. Nord also jumped through bureaucratic hoops to make these figures: Parks and Recreation, the Port of LA, City of LA Fire Department and Life Guard Department approved Nord’s fire-casting to sculpt the plastic on South Bay beaches. Nord’s figures are roped together by internal mechanics and external bureaucracies, suggesting what the human body relies on for short-term survival, which leads to irrevocable long-term dependencies.

In her 2009 article “Race As Technology,” for Camera Obscura, media studies theorist Beth Coleman discusses how the tools we use to wield power in this world and augment our six senses (think of contact lenses that are now 3D printable) become an extension of who we are. These tools are prosthetic: they allow us to more easily navigate the world and shape how we express ourselves. As a prosthetic tool, the internet provides mental space for online communities to exist. From Men’s Rights movements to Gun Control advocates, such communities reinforce, insulate and protect belief systems, giving them life and longevity. Nord’s work reinforces this implication: pulsing with data, the prosthetic limb becomes the entire corporeal self. In its quest for information, the human body has taken the complete computational form of circuits and plastic—making it more than just cyborgian, but totally unrecognizable. One might recall Yeats’ ambivalence about another kind of revolution: “He too, has resigned his part / In the casual comedy; / He too, has been changed in turn, / Transformed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born.”

-

1301PE: : Kerry Tribe

Kerry Tribe’s film Standardized Patient, which was commissioned by SFMoMA in 2017 and is currently at 1301PE, is a filmic expression of thoughtful storytelling centered on a controlled social environment that is often unexplored within the wooly conceptual arts—the doctor-patient relationship. This film’s storyline is based on a type of evaluation medical professionals undergo to complete their training using hired actors called standardized patients (SPs). The SPs describe their symptoms to medical trainees while also providing constructive feedback and grading. Hence those who diagnose mirror the diagnosticians.

Kerry Tribe, Standardized Patient (2017). Film still. Courtesy of the artist and 1301PE. Tribe’s precise filmic treatment of scenes, textures and micro expressions carves an isolated effigy from the relatively run-of-the-mill experience of doctor visits. Her deftness with camera angles and lighting, as well as the propulsion of performative acting within her characters’ expressions, such as side-long glances and pauses, creates a measured impression of the archipelagic thinking that occurs when groups of people come together to study one another, perceive and overcome misperception towards “accurate” and respected ascertainment. SP bridges the interiority of its subjects with their exterior network of interactions in a coldly detached fashion at times, given the film’s sterile venue of medical rooms. Needless to say this group dynamic goes beyond Tribe’s specific context.

Kerry Tribe, Standardized Patient (2017). Film still. Courtesy of the artist and 1301PE. A meditation on how humans communicate with one another within feedback systems, SP reveals group interaction as a process in which evaluating interlocutors negotiate ground, wherein plain prose communication results in the remote feeling of being understood “enough.” These communication endeavors conjure a “vector of truth’s nearness,” as William Falkner wrote, rather than straight-forward truths and revelations. SP is an acknowledgment of both our intellectual and emotional lack and fulfillment in intersubjective consensus; by filming clinical scenes that build dialogue around obscure sensations and symptoms of the body, this film demonstrates that while we are not a “hive mind,” no man is an island. We might mysteriously empathize with one another by yielding the stiff tools of scientific language so we can define our potentially inconclusive, emotional centers.

Kerry Tribe, “Standardized Patient,” March 24 – May 5, 2018, at 1301PE, 6150 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90048. www.1301pe.com

-

ltd los angeles: : I am no bird…

Some of us respect what makes people different from one another. By withholding judgment of others, we avoid enveloping them in our own contexts, selfishly assuming their futurities. Yet psychologist Marie-Louise Von Franz asserts, “Wherever known reality stops, where we touch the unknown, there we project an archetypal image.”

“I am no bird…” Installation view. Courtesy of ltd los angeles. Photo: Blake Jacobsen Try as we might, we cannot help typecasting in impassioned situations, like when we project ourselves onto our loved ones. In these instances, an inversion happens—and darkness falls: assuming he or she is always on your side, always on the same page, without flaws, or with too many flaws to count, we often deny what makes our lover(s) distinct from us. By attributing ourselves to them as an over-fixation, we deny our own existences as well.

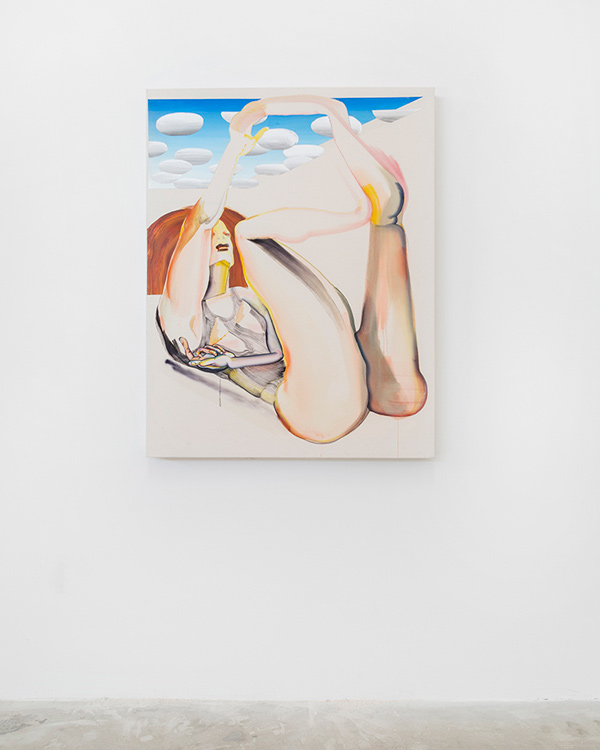

Sarah Faux, Just like that (good girl), 2017. Courtesy of the artist and ltd los angeles. Photo: Blake Jacobsen “I am no bird…,” the current group exhibition at ltd los angeles, highlights the discomfort of identity straying too far from itself, lensed through another—like straying paint strokes, out of bounds on Sarah Faux’s Just like that (good girl) (2017). The viewers’ expectations of body imaging and imagery is toyed with throughout: Chloe Seibert outlines the shape of a woman’s breasts with vinyl, steel, rubber, zip-ties on her Untitled screen (2016), as an unforeseeable (yet forgettable) scribble. Christina Quarles’ slick acrylic on canvas, And When the Clouds Clear, We Will Know the Color of the Sky (2016), depicts a flaccid woman “starfishing,” but not as a lingerie garnering femme fatale, sexually defined to be iTouched, but as a splayed fluid body, stressed by the specific gravity of the piece, like a floating wet noodle.

Christina Quarles, And When the Clouds Clear, We Will Know the Color of the Sky (2016). Courtesy of the artist and ltd los angeles. Photo: Blake Jacobsen Is life—which is far too short—a self-guided misdirection toward an uncertain yet formal articulation of love? To be embraced by another who sees or does not see what we see in ourselves, atomizing, even making obsolete our own interiorities, is the ceaseless human struggle this exhibition brings to light.

“I am no bird…” January 13 – February 10, 2018, at ltd los angeles, 1119 South La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90019. ltdlosangeles.com

-

@leiminspace:

Nihura Montiel

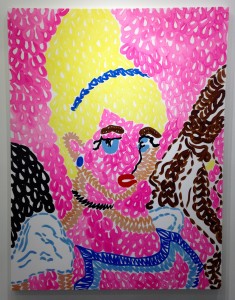

Nihura Montiel’s current solo show, “New Paintings,” now on view at @leiminspace in Chinatown delights in mimicking the various plush terrycloths and fabrics that function as fetish objects in her critique of misunderstood femininity. Her paintings of Cinderella, rendered in primrose, lacy yellow and hot pink, were brought suggestively to tumescence with bite-sized complimentary cupcakes embellished with edible pearls, Hershey’s Kisses ®, and wine. For the self-consciously feminine, the paintings and sculpture on view are a myth: they reveal the facile slippery slope women face between their girlishness and what they actually are.

Nihura Montiel, Terry Towel Cinderella (She Needs to Chill Out), 2016, photograph by Janna Avner. Braid Pillow (2016) is likewise contradictorily upheld (invisible to the viewer) with a double-braced metal clip, offsetting the plait of hair extensions carefully sewn onto the heart shaped piece. Framed by lace and a lacquered, black heart-outline, the pillow, which is painted canvas, is both saccharine and chimerical—as in Frankenstein’s monster.

Nihura Montiel, Braid Pillow (2016), photograph by Janna Avner. The well tailored wall piece Mood Leaf (2016) is a glossy, green tromp l’oeil of a plastic house plant. It complements the subtle impasto in Montiel’s portrait of Athena (Athena Bust with Cherries, 2016), placed next to a sanded depiction of Ovid’s Narcissus (Distressed Doodle, 2010), which is a variation of Echo and Narcissus (1903) by John William Waterhouse. Montiel’s is a clever craft: embedded in these pieces is vulnerable circumstance, a subjective self-portraitizing that is both comforting and self-effacing.

Nihura Montiel, Mood Leaf (2016), photograph by Janna Avner. The works accede to notions of ripening girlhood as a peachy and synthetic identification: they display the composite parts and descriptors of feminine identity (all fluff, no core) as the unbearable lightness of being female that is both maddening and unraveling. Montiel leaves some of that concern at the door though—as a playful and rosy expression of shrinking, neurotic, and fetishized femininity that one loves to hate, hates to love.

Nihura Montiel, “New Paintings,” February 20 – March 19, 2016, @leiminspace, 443 Lei Min Way, Los Angeles, CA 90012, www.leiminspace.com.

-

Reserve Ames:

David Muenzer

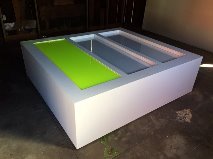

For his solo show at Reserve Ames, “Scalar-Daemon,” David Muenzer froze ingot molds filled with neon highlighter ink in an industrial freezer. He then stacked the frozen ingots on top of a platform placed in RA’s bucolic backyard shed. The platform has three recessed vitrines. Like frozen alien gold, the ingots melt, lemony-gossamer, into one of the recessed vitrines (now resembling an ink cartridge). They also slightly drip down the platform and onto the floor.

Highlighter Ingots (2015-2016) mischievously subverts the humorless minimalist legacy, turning a discrete unit or tube of color into its own reflexive anti-event. As a before-and-after, the sculpture comprises two visual experiences, transferring its vertical yellow y-plane into a honeyed-horizontal. This “scalar” system is more like a linear function with vectors, making Muenzer’s work hard to pinpoint, similar to artist Pierre Huyghe’s open-ended performance-events. When a thing is made to be radically altered, so vulnerable to the crystalline fragility of hydrogen bonds, it evokes a sense of terminus, of endings the most nostalgic of us often contemplate.

David Muenzer, Highlighter Ingots (2015-2016) courtesy of the artist and Reserve Ames. Photograph by Janna Avner. The piece is also an analytical resolution to a widespread problem: part of its cleverness lies in the fact that you can’t easily sell it (emphasis on “easily;” see Christie’s auction record of Tom Friedman’s Untitled pencil shaving, 1992). As the perfect non-event, ice melting is commonplace and ubiquitous. Performance-like, Highlighter Ingots might be as interchangeable and fungible as time itself. Minimalist Eva Hesse’s discussion of her work in 1968 becomes apropos: “It is the unknown quantity from which and where I want to go,” said Hess. “As a thing, an object, it accedes to its non-logical self. It is something, it is nothing.”

David Muenzer, “Scalar-Daemon,” January 24 – March 6, 2016 at Reserve Ames, 2228 Cambridge Street, Los Angeles, CA 90006, http://reserveames.com/.

-

Andy Robert @Full Haus/Los Angeles

A slate of concrete with blue Skittles scattered across it is illuminated by a clamp light in Full Haus’ current outdoor exhibition: “Andy Robert: Heavy Rain and Lightning.” Titled Dream Deferred (Skittles on Concrete), this simply executed sculpture seems commonplace enough: “‘Skittles and pavement’ were the words circling around me when I was coming to conclusions about the Trayvon Martin case,” explains Robert. “‘What happens to a dream deferred?’” asked Robert, echoing the opening line of Langston Hughes’s poem which is also in the press release for the show. Does it “‘crust and sugar over— / like a syrupy sweet…or does it explode?’”

Dream Deferred (Skittles on Concrete)

Concrete, skittles 35 x 35 x 2 inches 2015, photo by Janna AvnerRobert’s outdoor sculptures and installations reinforce the disturbing evidence in the Trayvon Martin case by responding to a particular fact: the Skittles and Arizona iced tea Martin had on him (and no weapon) during the time of his shooting. These items, Robert imagines, represent a loss of childlike innocence, social injustice and stunted dreams. Robert’s outdoor sculptures and installations also reveal his burgeoning semiotics as an open system with slippages in meaning.

When associated with a murder trial gone awry, Dream Deferred opens the viewer to a deadly absent referent (a lost life) and the work’s mundanity becomes an uncomfortable, suffocating silence—one that is associated with the lexicon of our cultural trauma over recent, preventable gun shootings.

Sometimes It Rains

Umbrella, fan blades, spray stone, metal 28 x 46 x 27 inches

2014After all, how does one memorialize injustice? An article from The Guardian states that Martin’s bag of Skittles remains unopened to this day and should “belong in a museum.” Perhaps this is so, but what if we open this bag, like Robert does, because nothing is ever neatly contained, nor remains immaculate forever? Many believe that the circumstances of Martin’s death reflect a callous disregard for human life, reminding us of the frailty of our mortality while also violating our sense of ethics. Robert’s work captures a nationwide lack of control and confusion that many feel over Martin’s case—and every other recently—that now speckles America’s consciousness as the awful “new normal.”

Andy Robert: Heavy Rain and Lightning

December 6th – January 31st

Full Haus

2042 Griffith Park Blvd

Los Angeles, CA 90039

-

David Bowie: Ashes to Ashes

David Bowie released his envoi-like album, Blackstar, on his birthday, and so a lightness of being seems to shine through his final week on earth. His lightness might be his general M.O., considering he made pop music out of lyrics about “sailors fighting in a dance hall,” and issues about self-evolution in his song, Changes, which celebrates changes that apparently aren’t always “so sweet.”

David Bowie, Photo: Mick Rock Bowie was an enigma and force of nature in his ability to churn out hits garnering millions of world-wide, die-hard fans. As a glam-rock star, Bowie sought new interpretations of what personal and public identity could be. His mischievous and jocular smiles recorded in his live 1972 performance of Starmanindicate a playful, onstage persona. Bowie’s career is comprised of shifting colorations in the various gender-bending outfits he donned, catchy beats, and arcane lyrics, which may reflect Bowie as an artist sensitive to the changing fluxes of culture, politics, social issues, and gender issues.

David Bowie, Photo: Terry O’Neil Bowie stated in an interview in the documentary, David Bowie Is (2014), that when he was just starting his career, it was easier for him to put on a persona as he performed, rather than be himself. Perhaps he didn’t quite know who he was just then. In the 1950s, Bowie was aping the hackneyed performances of his mentor at the time—an experimental mime. Documentary footage shows a white-faced Bowie prying himself out of an invisible box.

Arguably a more successful response to Bowie’s personal ontological questions is his creation of Ziggy Stardust, one of the greatest rock-legend personas in rock history. One might even suggest that his interests in new ontologies, the fragmented self and other alternative self-conceptualizations, stem from the struggle to maintain the singular “I” amongst the challenges of being an artist with a voice as unique as Bowie’s. One wonders if his interpreted persona was a life raft for some sacred idea of the self, which allowed for the dogged perseverance of Bowie’s long, successful career.

Ziggy Stardust, Photo: Lynn Goldsmith The art of persona is often the art of self-preservation, and Bowie’s art was as much his shield as it was his sword. Tony Visconti, Bowie’s producer, wrote on Facebook that Bowie’s “death was no different from his life—a work of Art.” Bowie’s success reflects in how he was able to transcend human concerns over the confusing plurality of existence, societal pressures, and personal preconceptions.