Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Gerardo Lammers

-

Guadalajara artist Jose Dávila moves around LA

When I heard the title of Jose Dávila’s recent book, Daylight Found Me with No Answer, it sounded familiar. During the years I was living in Guadalajara, I frequently talked with Dávila and other mutual friends at endless parties that lasted until dawn. But I hadn’t seen Dávila since those distant days and this was the first time I had ever paid him a studio visit. He was finishing a public project to be presented this fall at Los Angeles Nomadic Division (LAND).

Jose Dávila Portrait His studio is located on Colonia Artesanos in downtown Guadalajara in a workshop neighborhood whose chaotic atmosphere signifies what many consider to be a specifically Mexican aesthetic. Daylight Found Me with No Answer is also the name of a Dávila sculpture made of twisted metal frames.

Jose Dávila, Daylight Found Me with No Answer, 2013. Metal frames and enamel paint, 550 x 250 x 270 cm., Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2015. Photo: Alejandra Jaimes. This area also features many colonial churches (a couple of blocks from here there is even a church, El Refugio, right in the middle of Federalismo Avenue), dilapidated old houses with barred windows and central patios typical of early-20th-century architecture and streets lined with orange trees whose fruit nobody eats.

The façade of Dávila’s studio reveals only a number graffitied in purple, but when I cross the metallic threshold I discover an ample space with pieces made of rocks, concrete and glass. An assistant leads me across a patio filled with pots to a flawlessly kept library on the second floor, where I am given a refreshing glass of agua de ciruela amarilla. I am looking through the bookshelves when Dávila appears in a short-sleeve shirt, bermudas and white tennis shoes. He’s fresh from his honeymoon and the next day is his 43rd birthday.

Jose Dávila, Untitled (Duchamp), 2012. Archival pigment print, 174.8 x 133 cm.

Courtesy of Estudio Jose Dávila, Guadalajara, 2017. Photo: Agustín Arce.“I’m very happy to make an urban sculpture in Los Angeles; it is something new for me,” he tells me while seated at a large wooden table in another huge space of this—I now realize—enormous studio. Here, under a two-sided roof, I can see one of his paintings (from the series “A Copy is a Meta-Original”), one of his cut-outs (Duchamp and his Fountain) and on a small piece of paper pinned to an office board is a geometric shape that gives me a first glimpse of what will become Sense of Place, his work at LAND: a cube, 2.40 meters each side, made of concrete, able to separate itself into pieces — as Dávila says, like a Tetris game. After a first exhibit as a complete cube in West Hollywood Park, the sculpture will then be deconstructed and each part will be taken to different places, both public and private, in LA.

“The idea,” he relates, “is that the pieces should present themselves in different contexts. Then, after eight months, they return and form the cube again. The cube will say something about how LA as a city is made up of many mini-cities.”

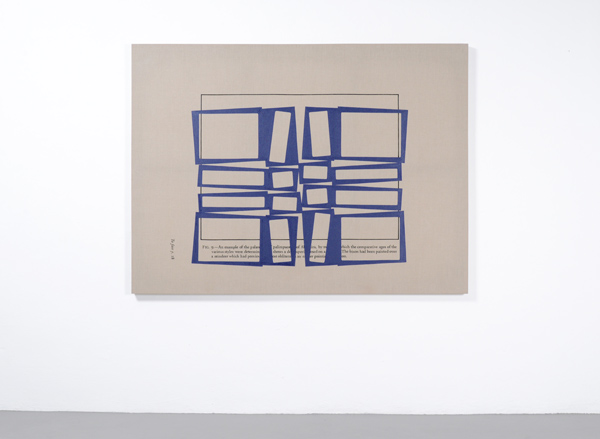

Jose Dávila, Untitled, 2015. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 200 x 220 cm., Courtesy of Galería Travesía Cuatro, Madrid, 2015. Photo: Agustín Arce.

Jose Dávila, Truly A Difficult Subject to Express, 2016. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 182 x 226 cm., Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2016. Photo: Agustín Arce. Dávila’s fascination with squares and cubes brings me to suggest that Sol Lewitt is one of his main influences; he adds the name of Josef Albers.

Although Dávila has been drawing and sculpting since he was a sedentary child — he was born with cancer, and treated for many years in a Houston hospital—he decided on finishing high school to study architecture rather than art. The old-fashioned oil-painting classes at the public school of art didn’t appeal to him, and when visiting the faculty of architecture at a private university he was attracted to the layouts and models on display.

I suggested to Dávila that Luis Barragán, the award-winning Mexican architect, might have provided his introduction to art and that he would have discovered the work of Josef Albers when he visited Casa Barragán for the first time. “Yes, indeed,” he confirmed. “Actually there is a story I love about this Albers painting that Barragán had in the hall of his house, the yellow one (Homage to the Square, 1969). It isn’t an original but a copy Barragán made himself. I understand that Albers, knowing who Barragán was, wanted to give it to him but Barragán said, ‘Oh, no, thank you. I don’t need a gift, I only need your permission to replicate it.’”

Jose Dávila, The Bison Had Been Painted Over, 2016. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 144 x 194 cm, Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2016. Photo: Agustín Arce. In the absence of good art schools and galleries in Guadalajara, Dávila and his fellows of that time —Gonzalo Lebrija and Fernando Palomar—had an idea that grew as time went by. In 2000 they created Oficina para Proyectos de Arte (OPA), a space based on the 22th floor of the Condominio Guadalajara—a functionalist tower, the first skyscraper in the city, with a spectacular view of the four cardinal points. Many contemporary artists were invited to work there over the next decade. The Albanian artist Anri Sala made his notorious work No Barragán No Cry (2002) there, in which Dávila helped Sala to ride a pony by elevator to the roof of the building. “OPA was for me a kind of master degree or even a PhD. It was really what helped me to learn lots of things I hadn’t studied. As a self-taught person, helping other artists produce their work was a school in itself,” says Dávila.

Jose Dávila, The Lips Are Bright Crimson, 2016. Acrylic and vinyl paint on loomstate linen, 168 x 126 cm., Courtesy of Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 2016. Photo: Agustín Arce. Some years have passed since then and Dávila now has a workshop and a growing reputation with international projects like the one in LA. At a point in his career when he can move wherever he wants, I wonder why he chooses to remain in Guadalajara. “Guadalajara gives me time,” he replies. “I mean, when I have been in other cities like Mexico City, New York or London, I realized these cities are very time-consuming places. There is great culture on offer but it takes hours to get around. By contrast, here in Guadalajara it takes me 10 minutes to get from my house to the workshop. I have all the time I want. I’d like to quote John Baldessari when he was asked why he lives in LA. He said it was because it seemed so horrible to him. If he’d lived in a beautiful city like Paris or New York he wouldn’t have arguments to make about art. I’d like to apply this sentiment to Guadalajara.”

I mention seeing a photo of his at OPA. I recall that nobody appears in it—there’s just a table with three computers and that’s all. “We had nothing,” Dávila remembers, smiling. “The truth is that many times we only went over there to listen music for hours on end.”

See Jose Dávila at LAND, 9/16/17–5/27/18, nomadicdivision.org.

-

We Don’t Need No Stinking Wall

If there is anybody more unpopular in Mexico at the moment than President Enrique Peña Nieto, it is, of course, Donald J. Trump. After a long list of aggressions, rudeness and even “jokes” by Trump, and in the middle of a big domestic crisis—both political and economic, rooted in corruption of Mexican government, but aggravated by the imminent breakdown of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—Mexicans already have enough reasons to shout.

“Fuck The Wall” is the title of an exhibition in Guadalajara, the country’s second biggest city, in the western state of Jalisco. Famous for its mariachis—the town of Tequila is less than an hour from the city—and its clusters of electronic enterprises, but also for its international book fair, its film festival and its huge community of college students, this regional capital is also a stop for poor migrants from Southern Mexico and Central America on their way to the North, and has a tradition of talented craftsmen and artists. Although this group of Mexican painters are far away from the border, they wanted to make a statement through a personal but also collective and—why not say it—joyful exercise.

“Nobody [from the Mexican government] had expressed a political stance. So, we decided to do it,” says Mauricio Magaña, the owner of 21st Century Art Factory’s gallery, site of the exhibition. Magaña, 45, is a crafts exporter who defines himself as “a frustrated painter.” Probably because of that and the need for more space for his art collection, he decided to open a modest and slightly improvised gallery that is in fact a workshop. Inside this warehouse, located in the Ciudad Granja neighborhood, close to Chivas soccer stadium, 20 men and women—brought together by Magaña and artist Pak Frank—were hurriedly working for two weeks in January to finish the artworks in time for Trump’s inauguration.

“The construction of this wall drives us back to medieval times of walled cities, and it is unacceptable to think that a 21st-century society such as ours can remain as a spectator in front of this decision,” proclaims the wall text of the show. Next to it hangs a depiction of Mickey Mouse’s four-fingered hand with its white glove offering an obscene signal: “Mexico salutes Donald Trump”.

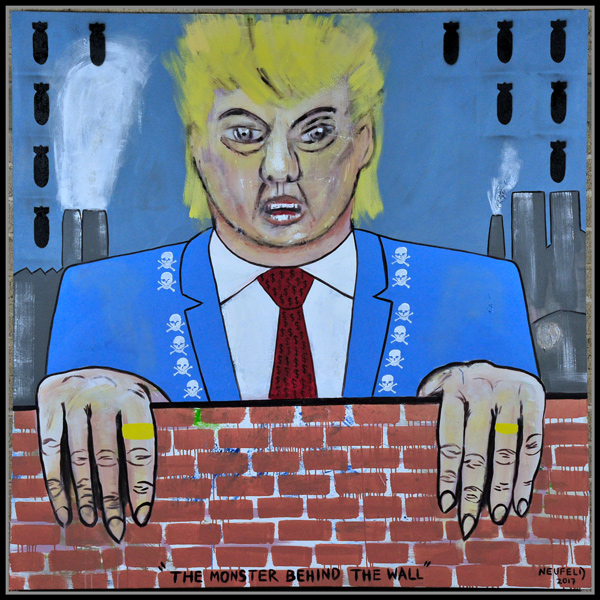

“It’s not only Trump, but the political, economic and army system,” says Daniel Neufeld, 44, whose painting The Monster Behind the Wall, a mixed technique on canvas that portrays a towering orange Trump leaning over the wall with bombs cascading in the background. Born in Guadalajara, Neufeld studied communication before he started painting. A few years ago, he and some peers—feeling “amputated” from mainstream but united by alcohol and parties—founded the collective Gangrena (Gangrene), with the manifesto: “Gangrena members want to rot away the beauty of ‘decorative’ art, of ‘easy’ art, of ‘indulgent’ art,” and aim to encourage non-elitist work.

Daniel Neufeld / The Monster Behind the Wall, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Despite the main topic of the show, he recognizes that: “I can criticize the gringo, but it’s more urgent that we Mexicans criticize ourselves.” For Neufeld the Trump issues served to distract Mexican people from the country’s major issues. Since the beginning of the year, besides the violence caused by the so-called Mexican War on Drugs, dating back to Felipe Calderón’s presidency (2006–12), people are complaining across the entire nation about the increase of gasoline prices, known as gasolinazo. But back to Trump’s wall issue, he adds, “I don’t know if it’s a science-fiction story or a fantasy, because of what it implies materially.” That’s probably why Neufeld painted those video game–type bombings.

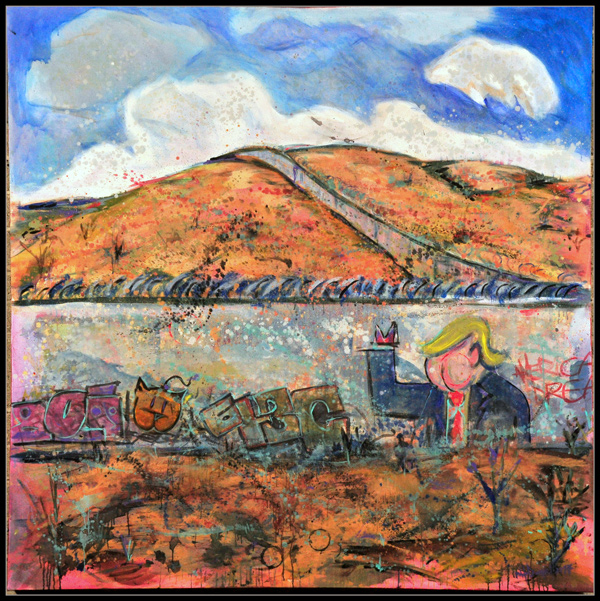

Pablo Arteaga, El rostro de la ignorancia, acrylic on canvas, 2017 Pablo Arteaga, 31, is an admirer of classic landscape Mexican painters José María Velasco (1840–1912) and Dr. Atl (1875–1964), and their understanding of nature; he is also a rock musician. The Anemic Apes and Los rucos de la terraza (Old Men of the Balcony) are the names of his bands. In his artwork, he imagines a desert landscape with a wall. A delicate, almost invisible, character is painting a mural on it with the figure of the U.S. President.

“I thought about the subject of nature [when painting this work],” Arteaga tells me. “Human frontiers are very absurd to me. Trying to break the harmony of the landscape by the means of a wall is nonsense,” he says.

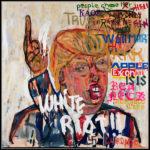

Mauricio Cárdenas, another participating artist, didn’t want to include Trump or the wall in his painting. “I preferred to depict the most dangerous, which is not Trump but the people who follow him.” He adds, “They are the wall.” Make America White Again, his piece, shows a crowd of happy Trump supporters, enclosed by a fence.

“U.S. citizens have the sovereign right to do whatever they want. If they voted for him, what can we do? But another thing is this demeaning attitude toward us, throwing away our relationship as allies. This is something I’ve never known before.”

“I wanted people from the U.S. to know that we Mexicans feel offended as neighbors. We don’t think this is a correct way to solve our disagreements. We share blood, oceans, nature, everything. Like it or not, we have to live together.”

Cárdenas, 40, an architecture school graduate, tells us he finished his artwork in one night, “I forced myself to do it this way. I didn’t feel this painting merited preciousness.” Based on thick strokes, bright colors and even some drippings, it resembles the work of some American classic cartoonists, like the Mad magazine comic strips.

Pak Frank, National Anthem, acrylic on canvas, 2017 “I don’t feel scared,” about the wall, says artist Pak Frank, 31. “People will find out a way of trespassing it and cover it with art.” Violeta Rivera, 37, an artist from Chihuahua but based in Guadalajara, had been painting a mural recently on the existent wall in Agua Prieta, Sonora, over the border from Douglas, Arizona, about some camel-men. “I portrayed these distorted characters carrying their belongings inside their bodies,” says the painter of You win, another piece in this show.

Pulse, Mi barrio me respalda, mixed technique on canvas “They can look at us strangely. But we are aferrados (stubborn). We know that we’re going to get ahead”, says Pulse, 33, a former graffiti artist who teaches art in a Guadalajara high school. His painting Mi barrio me respalda (My neighborhood supports me) presents, in a naïve and street style, a bunch of Mexican characters and symbols, including a kind of Quetzalcóatl snake, and even words of a Control Machete song, encircling a blurred, enormous and fluorescent Trump head.

The gallery owner and his team want this show to be itinerant, hoping to find a final destination in the U.S. “Maybe some Democrat will be interested,” says Magaña.

SEE MORE PAINTINGS IN EXHIBITION HERE:

Violeta Rivera / You win, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Daniel Neufeld / The Monster Behind the Wall, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Sergio Domínguez “El Jagger,” Premonición combustible, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Tehuti Cortez, El billete, oil on canvas, 2017 Mauricio Cárdenas, Make America White Again, acrylic on canvas, 2017 Pablo Arteaga, El rostro de la ignorancia, acrylic on canvas, 2017 Manuel Rodríguez, Sin título, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Sadek Reynolds, La bandera del tío Sam, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Pulse, Mi barrio me respalda, mixed technique on canvas Pit, La gran manzana, ink on canvas, 2017 Mevna, Make America Great Again, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Alex Martínez, Bullet in the head, oil on canvas, 2017 Gustavo Islas, La nave de los locos, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Manuel Guardado, Don Trumpas, acrylic on canvas, 2017 M. Galindo, El beso de Judas, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Pak Frank, National Anthem, acrylic on canvas, 2017 Feng, El dólar es una mentira, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Dyeto, Fuck Trump, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 Dyer, El muro de las lamentaciones, mixed technique on canvas, 2017 All photos by Jorge Sevilla.

-

Zona Maco Art Fair Report

As every year, since 2004, Zona Maco, one of the most important Latin American art fairs, was carried last week in Mexico City with the participation of more than 150 galleries. Founded by Mexican Zélika García, Zona Maco is such a big and social event in a city plenty of museums—170 according with the Ministry of Tourism—and with an increasing number of contemporary art galleries.

Besides international and well-known like Americans Gavin Brown, Gagosian, Sean Kelly and David Zwirner, or the Parisian Laurent Godin, this edition was characterized for the prevalence of Mexican galleries like, Luis Adelantado, Arredondo/Arozarena, Patricia Conde, Hilario Galguera, kurimanzutto, OMR and Proyectosmonclova from Mexico City; Curro, Páramo, Tiro al Blanco and Travesía Cuatro from Guadalajara; GE from Monterrey; and Yam Gallery from San Miguel de Allende. RGR+ART (Caracas), Vermelho (Sao Paulo) and Walden (Buenos Aires) were among the few participants from South America.

Galleries from LA had also a meaningful presence. Overduin & Co., Regen Projects, Luis De Jesús, Marc Foxx, ltd los angeles, Steve Turner and Mama gallery, attended.

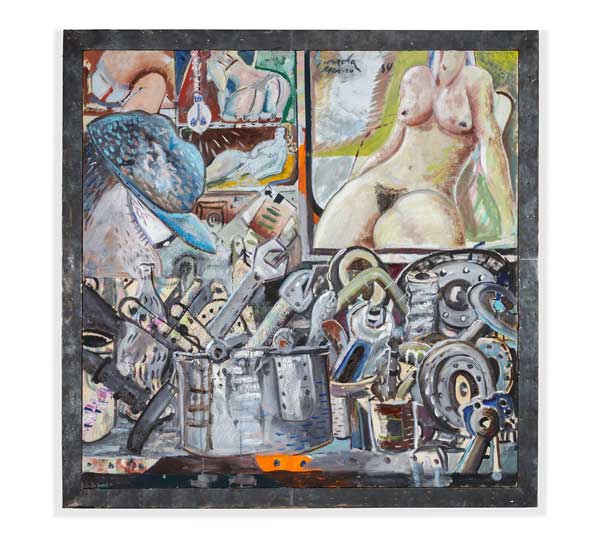

Courtesy Fundación Gurrola, Photos by Omar Olguín Mexican House of Gaga, which recently opened a space in LA, drew attention with its exhibition of Juan José Gurrola paintings. Gurrola (1935-2007) was a Mexican artist, best known by his theater plays, performances and extroverted personality. The artworks presented honor artists like Philip Guston.

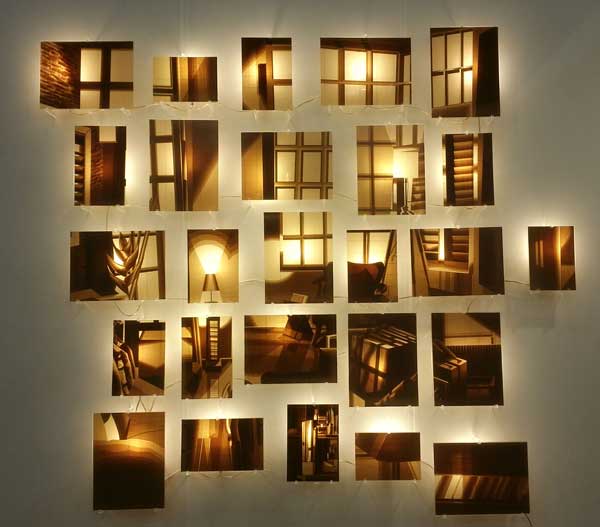

Osvaldo González,Hábitat, de la serie Espacios de memoria, 2016, Installation (acrylic, adhesive tape and lights) On the other hand, Puerto Rican Galería Agustina Ferreyra and Cuban Servando Galería de Arte were part of New Proposals section. Based in Havana, Servando showed artworks of Leandro Feal (photography) and Osvaldo González (light screens).

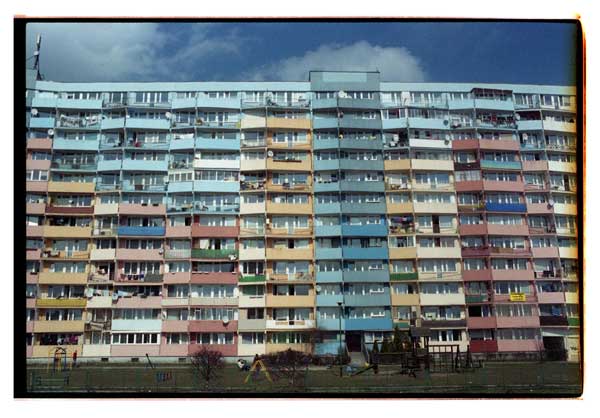

Leandro Feal, Sin título, de la serie Eastern, 2013-2014, C-Print on Fujicolor Crystal Archive Pearl paper And for the lovers of modern art, Zona Maco had a specific section with the participation of galleries like Galería de Arte Mexicano GAM (Mexico), Jean Mathieu Martini (Paris), Smith-Davison Gallery (Miami/Amsterdam) and Galerías Cristóbal (Miami), among others. Artworks of Mexican classics like Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Rufino Tamayo, Mathias Goeritz (German-Mexican artist), Jesús Guerrero Galván, Agustín Lazo, and Chucho Reyes Ferreira were exhibited.