Your cart is currently empty!

BOOKS: Hold Still

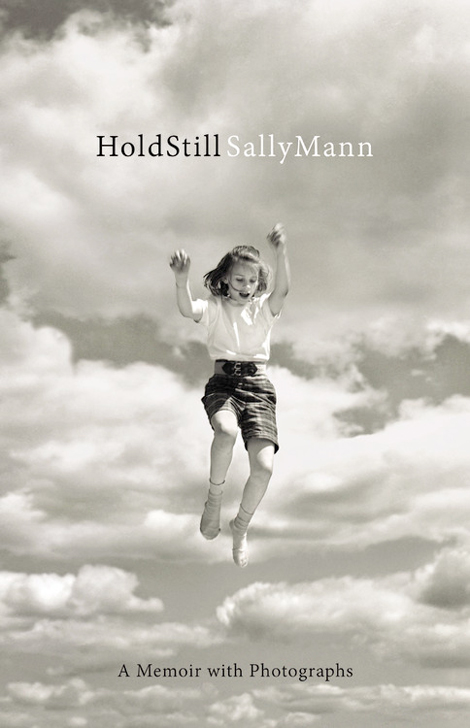

Part journey of self-discovery, part family history, part window into an artist’s oeuvre, Sally Mann’s memoir Hold Still is simply wonderful, sharing that same combination of hauntingly beautiful lyricism and truth that are the hallmarks of her photographs.

For most readers it will come as a revelation that this giant of the American visual art world also holds an MFA in creative writing from Hollins University. This explains somewhat Mann’s literary facility, but judging from the excerpts written as a teen included in the book, she had the aptitude all along. Writing, for Mann, preceded photography as an interest and it has remained a “twin passion” throughout her life.

Mann’s tone is both literary and conversational. Her prose is at times ornate, embellished with erudite and unusual vocabulary; but then, out of nowhere, Mann will throw in a curve ball of slang, or some homespun Southernism that blasts fresh air onto the page. As much as she reveals about herself in the actual narrative, the way she writes does a pretty neat trick of doing so as well. You can tell she’s whip smart, full of artistic and personal integrity and very funny.

Mann’s character was forged in genteel Lexington, Virginia, and the rigorous environment of New England’s Putney School and Bennington College; she was also hugely influenced by her disciplined and principled father whom she adored despite his emotional inaccessibility. The grandson of the inventor of a vastly lucrative cotton-baling machine, Robert Munger turned his back on the Dallas society from whence he came to pursue a life as a country doctor. His passions were art, travel and fast cars in which he indulged sparingly, but well, acquiring works by Kandinsky, Matisse, family friend Cy Twombly, and an Aston Martin.

It used to be families like the Mungers—well-educated, enlightened and worldly, the kind of people who set more store by ideas and culture than material things—weren’t that uncommon, but sadly now they seem quite rare. Raised in a kind of benign neglect, little Sally was left to run around jaybird-naked, her father’s pack of Boxer dogs her only playmates. A living, breathing version of Scout Finch, Mann had a close and loving relationship with the family’s black housekeeper—in essence a surrogate for her coolly aloof mother. Mann’s description of Virginia Carter (aka “Gee-Gee”) is beautifully wrought, frank and affecting.

Transitioning from near feral child to sassy teenager, Mann blossomed (as the photos in the book attest) into a stunner, bearing more than a passing resemblance to a young Jane Fonda. You get the sense things would have turned out quite differently for her if she hadn’t been sent packing to the Putney School. There, she was initially a fish out of water, but the place would be the making of her: “Confused, but not defeated, I began to mint a new currency based on qualities valued at Putney: creativity, intellect, artistic ability, scholarship, political awareness, and, most important, cool emotional reserve.”

At Putney she discovered photography and William Faulkner. Absalom, Absalom! “…opened the door to the future, after which the world is never again seen in quite the same way.” Of Faulkner, Mann says: “My homesick romanticism thrummed to the melodrama: the violence, the undertone of sexual threat, the sense of moldering decadence, the cursed inheritance, and, of course the inevitable haunted home place. That haunted home place, a metaphor for the South itself, was a house divided by the institution of slavery.”

Up in New England, Mann also learned how inextricably bonded she was to the southern landscape, a landscape “ …extravagant in its beauty, reckless in its fecundity, terrible in its indifference, and dark with memories” that together with death and family would form the wellspring of her art.

The section on Mann’s photographs of her children reveals not only how the photographs were made but also demystifies her artistic process. Discarded images shown alongside the final one help illustrate this. The controversy surrounding these photographs is well known, but the siege of whackjobs, finger-waggers and most alarmingly, sexual predators, Mann and her family had to endure is horrifying to read about. Although, Mann’s disclaimer about the title “The Perfect Tomato” (a picture of her daughter dancing nude) may be hard to swallow, she lays out a good defense on other counts. “Unwittingly, ignorantly, I made pictures I thought I could control, pictures made within the prelapsarian protection of the farm, those cliffs, the impassable road, the embracing river.”

Whether discussing, the shocking murder/suicide of her in-laws, personal details of her parents’ marriage, or her visits to the University of Tennessee’s Anthropology Research Facility aka the Body Farm, Mann doesn’t flinch. She looks the subject of race relations in the South squarely in the eye, devoting many pages to it and owning up to her participation, albeit as a child, in the “stunningly unexamined” inequities of segregation.

Mann can certainly spin a yarn, but she was helped in this particular effort by the extensive family records boxed up in her attic. That she could even confront them speaks volumes about her tenacity and workmanlike attitude, qualities she claims are etched deeply in her DNA. The papers enabled her to piece together an extraordinarily detailed familial account that connects the dots down the genetic line between heredity, experience and personality. Many family photographs are included in the book adding a fascinating visual element to the reader’s experience.

Hold Still covers so much ground with such diverse topics, it could make for a bumpy ride. But Mann’s prose glides effortlessly from one subject to the next with not the slightest shudder of gears shifting. Not for nothing has the book garnered widespread accolades, including being nominated for a National Book Award and Carnegie Award. Hold Still is a tour de force of writing that establishes Mann as a major literary voice.

HOLD STILL

A Memoir With Photographs

By Sally Mann

482 pp. Little, Brown & Company. $32.

Comments

One response to “BOOKS: Hold Still”

Fascinating artist, fascinating review!