Your cart is currently empty!

BOOKS

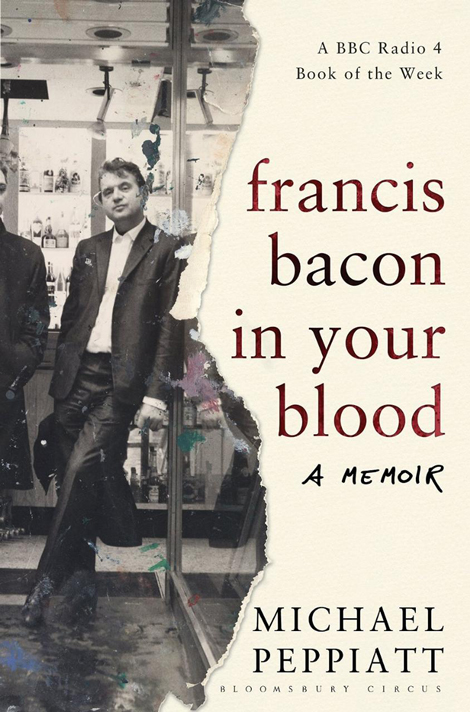

According to his Wikipedia entry, this is Michael Peppiatt’s eighth book about Francis Bacon. If all of his Bacon books were packaged like a deluxe DVD, this would be the really good feature length documentary about the “making of.” He certainly deserves to tell his own story. For three decades he was Bacon’s Boswell.

The story opens with the author’s machinations to land an interview with Francis Bacon for his college newspaper in 1963. Bacon agrees, and invites him into his world. As Bacon, by his own admission “can’t even write a letter,” the prospect of an official historian 30 years his junior, in need of a father figure, must seem a perfect fit. By this point in his career Bacon is earning enough to be casual about money. There are tales of taxis from gambling dens back to the studio to search paint cans for wads of cash. His ongoing access to the inner sanctum where Bacon worked combined with Peppiatt’s well-honed powers of observation provides us a glimpse of how it must have felt when it was alive with Bacon’s presence.

Since he hasn’t figured out what he wants to write about after he graduates, he is available to accompany Bacon on his nightly rounds of the high and low drinking establishments. Bacon loves the attention he is getting and starts making pronouncements that he urges Peppiatt to write down every night after they part ways. Much of this book is derived from those diaries.

One of the pleasant surprises about this book is how un-salacious the tone remains. Bacon’s taste for whippings by brutes and truck-driver types is covered in the official bios that have footnotes. When he addresses these tastes, it is usually to express concern for Bacon’s well-being. What is causing him to limp today? How did he get that bruise? Peppiatt is heterosexual, and not Bacon’s type, so there is never the discomfort of an attempted seduction gone wrong. Some of the sweetest passages focus on Bacon’s lover, George Dyer. The myth goes that he met Bacon while trying to rob his flat. Bacon invited him to stay. When George kills himself on the day of Bacon’s major opening at The Grand Palais, we are afforded a glimpse of the trooper who knows that the show must go on. A decade earlier, during the show at The Tate that broke Bacon into the history books, the congratulatory telegrams included one informing him of the death of the love of his life.

Although the author is having some success as a freelance art reviewer, his dissatisfied mother finds him a job with a French publisher. When Bacon visits Peppiatt’s flat in a dangerous neighborhood in Paris, he solicits him to find Bacon a studio in France. Bacon is a product of an era when the center of the art world was Paris. The two modern painters he respects lived there (Picasso and van Gogh), so he longs to work there too. When Peppiatt finds him a studio, Bacon purchases it in his name. Bacon can be generous with friends to a fault. He blames himself for George’s death, with the rationale that George would only be in jail if Bacon hadn’t “rescued him” into a life of boredom and helplessness.

In the mid 1980s it seemed like an appropriate time for an official biography, and Peppiatt cautiously approached Bacon. Bacon immediately agreed. Preparations were made for a prestigious art magazine to excerpt portions, and ran them by Bacon, who called the next day and insisted that none of the material could appear in print while he was alive. Forced to choose between his friendship with Bacon or a prestige magazine, he stood by Bacon. It was this experience that caused them to grow apart. The other thing that drove a wedge was Peppiatt’s decision to embrace fatherhood.

Bacon was about 50 and fully-formed when they met. Although he could go on ad infinitum about Proust and Joyce (and recite the occasional classic poem) he professed to hate novels, and carried on a routine that would have precluded reading. He got up every morning and painted with a raging hangover. Then it was off to the clubs, the restaurants, and wherever there were brutes. This book is a well-written account of a world that no longer exists. It is warm, affectionate and funny. If you are not already a Bacon aficionado, you might want to start with Peppiatt’s 1997 biography. If you are avid about Bacon, this is the book you’ve been waiting for.