Your cart is currently empty!

Year: 2011

-

Editor’s Letter

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, ARTILLERY! 5 YEARS OLD!

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, ARTILLERY! 5 YEARS OLD!ANNIVERSARIES MARK cycles, patterns, reasons to keep going. If you make it one year, you might as well go another. All of a sudden, it’s five years. Now you’re committed. I could apply that logic to quitting smoking (which I did) and to startingArtillery.

My soon-to-be co-founder said, “Let me finish my book, and I’ll help you start your art magazine.” But it was what he said afterward — “Remember, once you start, you can never go back” — that still echoes in my mind today.

Amid my paranoia and delusions of grandeur, we did put out our debut issue of Artillery, with Paul Takizawa as art director and my husband, Charles Rappleye, as publisher. I didn’t know what Artillerywas yet. I was just making art, only with words and a computer. Our first issue featured Catherine Opie breast-feeding her son. It’s a famous photo now. I think Regen Projects never forgave us for that. We didn’t know any better, really. We butchered the image. We cropped the hell outta it, blew it up, overlaid type, put another image by Opie on top of it — everything imaginable that was against all the rules. If you’re reading this, Cathy, please forgive us, for we knew not better.

After Opie, there was an artist, Andrew Krasnow, who used human skin as his medium. He made an American flag out of flesh — dyed red, white and blue. He held his “flag” to the camera, and that ended up as our third cover. That seemingly patriotic image, with our logo — just the word “artillery” — made it clear to us that it wasn’t clear to others what the magazine was all about. And that is when — many miles from Miami, on our way home to Los Angeles in a rented car after our first art fair — the subtitle “Killer Text on Art” was conceived.

We steadily built an audience and started to make our presence felt. We changed printers after we were censored twice (thanks to David Humphrey’s visual column, New York Barrage). By then, there were two other start-up art magazines published in LA — one is gone now, but the other remains. After our lone ex–LA Weekly sales rep stopped showing up and started signing his e-mails “God Bless You,” we weren’t entirely sure what our fate would be. Then came Paige Wery (dare I thank God?), who became our publisher in January 2008.

Paige coming onboard felt like our second act, along with the arrival of our creative director, Bill Smith, who joined us around the same time. Bill brought skills honed at Mean magazine and a new look, cleaner and slicker, while Paige took over advertising and pushed us from 64 to 80 pages, and today 96 pages. Our events and her Live Art Debates make her a tour de force and someone to be reckoned with — just ask our advertisers! She’s made Artillery a staple at art fairs and helped establish us as LA’s premier contemporary art magazine.

The beginning of our fifth year could open our third act. That sounds a bit premature, but we feel confident the best is yet to come; with several new writers and editors, the Artillery team just keeps getting stronger.

Thank you, Los Angeles art galleries, dealers and institutions. You made us what we are today. Without your support, there would be no Artillery. And thanks to all of my loyal contributors, who excel with their writing skills and pitches and stay on top of it. I definitely couldn’t do it without you.

And finally, to you, my dear readers — who else would I write this letter to? I thank you for sticking around, because we’re sticking around too.

—Tulsa Kinney

-

Fashionably Macabre

Of course I knew of bad-boy provocateur Alexander McQueen’s reputation as a brilliant couturier, with words like “artist” used to describe him, but such hyperbole is thrown about willy-nilly in the fashion world, and I just assumed it was an exaggerated way of saying he was really talented. “Savage Beauty,” the exhibition, which spans McQueen’s 19-year career at the Metropolitan Museum, changed my mind.

An unlikely fashion darling, McQueen triumphed in that difficult world by dint of hard work and amazing talent. But he never seemed dazzled by it all, maintaining a healthy cynicism throughout his career. Working class and overweight (he did eventually slim down), McQueen was also gay, which must have been a burden growing up in London’s tough East End. Thrice an outsider, McQueen developed within his steely self a rare empathy with the downtrodden and outcast and a richly honed perspective that made him constantly question the status quo.

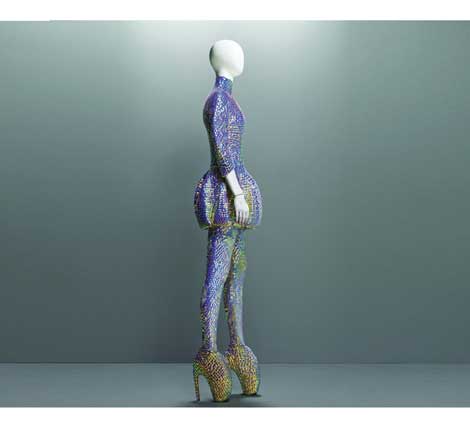

There is no shortage of beautiful clothes showcasing McQueen’s renowned tailoring skill in the first couple of rooms. These are clothes with attitude, referencing S&M mixed up with Victorian romanticism. McQueen liked his women fierce and viewed his designs as a kind of armor that would shield and empower them.

Cabinet of Curiosity It is in the room “The Cabinet of Curiosities” where things get really interesting. Here shelves and niches along the wall display some of McQueen’s more outré dress designs and various accessories, shoes and headgear he created in collaboration with jewelers and milliners. There are also videos of his fashion shows. These extravagant spectacles, with their bizarre take on beauty, enigmatic story lines and over-the-top garments and makeup, reminded me immediately of Matthew Barney, not in a derivative way, but in a parallel way. One dress with an anatomically correct lilac leather bustier atop a wide horsehair skirt, matching leather hood and horsehair “pony tail” was particularly Cremaster-worthy. Though I could find no paper trail connecting the two, I am sure they knew each other and were members of a mutual admiration society. McQueen collaborated early on with Björk, Barney’s wife, and both men, as part of their explorations into the nature of beauty, used the double-amputee model Aimee Mullins in their work. The beautiful carved wood boots McQueen designed for her (that many in the fashion world initially took for conventional boots, as opposed to prosthetics) are on display here.

Another dress, with a splatter design of paint, is exhibited next to a video showing its creation during a fashion show. Two robots shoot paint at the model as she revolves on a stand between them. Loaned by an Italian auto factory, the robots are sinister, Transformer-like with their wildly waving robotic arms — you can only imagine how nervous you’d feel sitting in the audience waiting for them to turn on you. Still another dress features a carved balsa wood skirt that flares out to at least four feet in back.

There’s a carved wood Chinese village headdress, which I imagine would be much like wearing a dollhouse on one’s head: a twiggy, upside-down nest of a “fascinator” composed of enormous porcupine quills and many examples of McQueen’s extreme footwear, including the notorious hoof-like clodhopper known as “the armadillo.” One of the real highlights is an incredible metal ribcage and vertebrae complete with curling tailbone. It’s a gorgeous piece of stand-alone sculpture. Seeing it as a kind of body art that someone would wear sparks an unsettling visceral reaction. I overheard one viewer remark: “It’d be tough going to the theater in that one.” I know she was making a joke, but she got to the crux of the matter. None of these items were really meant for public consumption; they were made for the runway and are part of the statement McQueen was making about his vision and himself. Yes, they were powerful marketing tools, and some may shy away from the overt commercialism that suggests, but they fulfill my criteria for art.

Alexander McQueen, gallery view, The Romantic Mind From a purely aesthetic standpoint, I think my favorite part was the Romantic Exoticism section, which featured extraordinary embroidery. At Givenchy, McQueen became exposed to the rarefied world of haute couture, embracing many of its techniques and tempering somewhat the fierceness of his designs. One beautifully tailored dress, a combination kimono and straitjacket, was particularly powerful, speaking volumes about fashion and its subjugation of women. Here too was a hilarious East-meets-West amalgam, a playful silk romper complete with an obi worn with American football shoulder pads and helmet painted with delicate Japanese designs.

McQueen took inspiration for his shows from film, history, art, African tribal garb and nature. His Scottish heritage figured prominently in his work, in particular the centuries of oppression that occurred there at the hands of the English. McQueen incorporated feathers, horns, shells, bird skulls and caiman heads into his clothes, and in one of his final shows, “Plato’s Atlantis,” he developed a technique where digital images of animals and insects were woven into fabric.

One of his more provocative explorations of beauty and ugliness was inspired by a Joel-Peter Witkin photograph featuring a grotesque image of a fat, naked woman wearing a weird, fetishistic full-face mask and breathing through a tube. McQueen incorporated it into his 2001 Voss fashion show, which took place inside a giant mirrored box that reflected the appearance-conscious audience’s images back to them as they arrived. For the finale, the mirrored glass walls of a second box at the center of the room came crashing down, revealing a tableau vivant re-creation of the photograph. In this setting, where beauty had just been the focal point for the greater part of an hour, it must have been immensely shocking. It was pure McQueen. As he once said, “I don’t want to do a cocktail party, I’d rather people left my shows and vomited. I prefer extreme reactions.” But in this case, there was more to it than that, because it strikes me as intensely personal knowing McQueen’s own status as outsider.

McQueen was fascinated with death; morbid themes are constant in his oeuvre. Early on in his career, in a nod to Victorian funerary jewelry, McQueen included a lock of his hair as part of the label in each garment. At one fashion show in a church, he placed a skeleton in a front-row seat, and he topped an opulent ostrich-feather evening gown with a bodice of laboratory slides on which fake blood had been painted. What is remarkable about this dress, and all the rest for that matter, is that, despite these unorthodox materials, McQueen never sacrificed design or beauty, and so the end result is absolutely stunning. You’d never think the shimmering rectangles were anything but over-scaled pailettes unless you read the description.

The catalog accompanying the Met show features an eerie hologram on its cover, which changes back and forth between McQueen’s face and a skull. The catalog is unique in that photographer Sølve Sundsbø shot the garments on live models and subsequently manipulated the images to make them look like mannequins, complete with joints. There is a veracity to how the clothing looks on the body and an eeriness to the living flesh, supported by real muscle and bone, transformed into lacquered fiberglass.

One comes away from the exhibition very moved by the depth of McQueen’s passion, his incredible imagination and his pain. He was a fragile soul, committing suicide in February 2010, nine days after his mother succumbed to cancer and three years after his friend and champion, fashionista Isabelle Blow took her own life. McQueen burned with such intensity, producing two couture and two ready-to-wear lines every year, and presumably double that during his tenure at Givenchy; one feels he simply wore himself out. For McQueen, who was compelled to delve so deeply into his core for inspiration, the effort was enormously draining. Looking at his body of work, one is bowled over by the sheer beauty and creativity, but you can also clearly see the blood, sweat and tears writ large amid the satin and silk.

All images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

SOAP DISH

The mid-afternoon New York City traffic is uncharacteristically brisk on my way to interview performance artist Kalup Linzy. I arrive in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, half an hour early, with my photographer. Linzy greets us at his unmarked live-in work-space basement studio wearing a shiny dark gray satin shirt, white boxer shorts with orange and brown hibiscus flowers and a pair of rubber flip-flops.

Welcoming us in, he exclaims, “I know I told you 2 p.m., because The Bold and the Beautiful goes off at 2 o’clock.” Linzy pauses, “I mean, I can make exceptions.”I am grateful, because this man is serious about his soaps. His most acclaimed work is a series of self-made soap opera videos, some of which are All My Churen, Da Young and da Mess and the ongoing serial “Conversations Wit de Churen.” They are equal parts gender-bending satire, daytime high drama and genuine heartfelt homage.

Kalup Linzy, “Keys to Our Heart,” 2008, still from digital video Before excusing himself, Linzy announces that he’s going to make some popcorn because he has the munchies. He returns with a bag of microwave popcorn, wearing a brunette shoulder-length fuchsia-tipped wig. We want to take photos outside to catch some of the early spring light, but Linzy objects, “I can’t be going out like this; school will be getting out soon. I don’t want that kind of attention. You know how some high school boys can be.” He pauses, then adds, “But of course I’ll beat their ass!” The threat is difficult to believe. There is an easy grace about him: his newly added tresses framing his deep soulful eyes, his wide soft smile caressing the scruff of his beard.

Kalup Linzy, “Keys to Our Heart,” 2008, still from digital video The wigs, high fashion and glamour that have become a hallmark of Linzy’s work don’t necessarily define his real world. “I’m not transgender; it’s not a lifestyle for me. I just use the aesthetic of drag in my work, but I don’t think I’m a drag artist either. I just decided consciously that whenever I was going to appear that I would be dressed up and performing because I think of myself as a guy who is pretty boring,” he says laughing. “I mean, that’s what the work is, but I didn’t necessarily want to be my characters from the videos. People are annoyed that it isn’t real, but I’m like ‘whatever — get ready!’ As people misunderstand, they’ll research my work more. There are many layers to a man putting on a dress. We’re all drag queens and drag kings, anybody who’s performing to create an identity.”

Linzy’s identity seems delightfully complex. He counts his influences as everything from daytime dramas, old black-and-white Hollywood movies, the romanticism of the Harlem Renaissance to Def Comedy Jam and the sitcoms of his childhood. He draws artistic inspiration from Andy Warhol, John Waters, Glenn Ligon and Lyle Ashton Harris. Munching on a handful of popcorn, Linzy muses, “When I was in college I had this Black Male Body book. I remember that exact moment I saw Lyle Ashton Harris, in like a tutu. I connected that to John Waters in my mind, and that sort of began to give me the freedom to do my work.”

Despite Linzy’s rather grand ascension into the art-world elite, he seems fairly unaffected by it. “I feel like the world is my art community anywhere I go. You hang out with the people that you’re around and working with and let the energy come and go. It’s like a fleeting experience. But I really do feel like the world is my home.” One of the “elite” that Linzy has been hanging out with recently is actor James Franco. They met in 2009 when Linzy was performing at a party for Art Basel Miami Beach. Last year, Franco asked Linzy to join him on General Hospital during his stint playing a deranged artist/serial killer, Robert “Franco” Frank. In an art-imitates-life twist, Linzy played Franco’s musical collaborator singer and performance artist, Kalup Ishmael.

This was a “full-circle moment” for Linzy: “I grew up wanting to be on a soap opera. I grew up wanting to be a filmmaker, a director and wanting to sing. I incorporate all this stuff into my art. So when somebody comes along like James Franco and says, ‘You wanna be on General Hospital?’, of course I’m going to say yes. The whole point of me doing the videos is because I didn’t think a soap opera could ever happen to someone like me. I didn’t believe it at first, but then I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is really happening!’” Linzy is grinning. “It was a big event in my life! I had to rethink, because it really wasn’t supposed to happen in a million years. Especially because I had decided to be openly gay and not give a shit and instead just express it through my work. But it gave me the confidence to do more and follow more of my dreams.”

Linzy is reflective when talking about those early years growing up in Clermont, Florida. “When I started making art in my late 20s, I was confronted with things that I had missed or was missing, things I needed to confront and deal with. Like I grew up — my mother didn’t raise me. She was schizophrenic and on drugs for a period of time. I realized I had abandonment issues, but I would not deal with them. Moving to New York made me look that in the face. Just to really look at it and know how it affected things I did. It made me want to be a giver, to feel good about something. There are certain things that I didn’t get, and so I became more inclined when I was making my work to make something just for myself, or people who are like me to identify with and enjoy.”

Upon first impression, Linzy’s work may seem like zany high-camp performance art. It’s challenging to watch his soap opera video series and not get sucked in by the characters. You immediately want to tune in to the next episode and see how it all plays out — a common soap opera strategy. “In comedy, the tragedy happens first, and then the journey back from that is normally humorous, you know, to try to heal it,” Linzy says.

Kalup Linzy, Photo by Cecilia De Bucourt High and low art brazenly crash into each other in Linzy’s work; any notion or division between the two is unimportant to him. While grateful for his success, he is unimpressed by art-world politics. “I remember being at MoMA, and I basically told the audience that I didn’t care what they thought, and I think people probably didn’t appreciate it too much, but I felt like I had to set myself free from these other people’s opinions. All they talked about was these crack addicts in the ’80s, but my mother was one. They talk about being gay, but I am one of them. They talk about being black, but that was me. Everything I felt I was a part of was being marginalized. I had to set myself free from all these opinions to be able to live.” Linzy pauses, becomes quiet and crumples up the popcorn bag. “It’s not the easiest thing. I think it’s important to care, but you have to have some kind of detachment at particular points in order to just survive and not emotionally kill yourself. The work became about my own healing and hopefully other people get something from that. I’ve done a good job with it. I’ve grown, and I’ve learned. It’s okay to let go of things you didn’t get and not dwell on it … and it’s okay to be liked. Everything doesn’t have to be so heavy all the time, you know. Early on I was just doing things so I could be accepted, but now my work is really about accepting myself.”

Linzy gets up and loads a dance mix on his laptop; the music floods the room. Suddenly we’re all up on our feet dancing and laughing. His words echo in my mind: “Everything doesn’t have to be so heavy all the time.” The photo shoot begins. Linzy serves up a powerful supermodel turn to the camera with an “I’ll beat your ass” diva glint in his eye, and suddenly I can plainly see a man in a wig who can take care of business if and when he needs to.

Greg Walloch is a writer and performer in Los Angeles. For more information, visit www.GregWalloch.com.

-

MILF AS MUSE

It is difficult to imagine John Currin’s work adorning walls more modest than those of the uptown Gagosian Gallery in Manhattan. Currin’s subjects have become progressively more well-heeled as his career has advanced. His signature subjects of yore—the ludicrously big-titted women and the frail women in bed and the nymphettes clinging adoringly to wilting bearded aesthetes—are a thing of the distant past; he has now entered a sphere of affluence commensurate with the incomes of the select few who can afford to collect his paintings, which now sell in the million-dollar range. And why shortchange him? He is one of the most interesting painters around, justifiably extolled for his technique. There are other comparably gifted modern masters (Vincent Desiderio, Lisa Yuskavage), but none who ply their exquisitely wrought brushstrokes in the service of perversity quite as cleverly as Currin.

Though they do not comprise the bulk of his oeuvre, it is Currin’s depictions of the sex lives of the rich and complacent—in which porno-derived tropes of the Sapphic variety are transposed to upscale surroundings—that receive the most attention. The most prominent piece at the recent Gagosian show, The Women of Franklin Street, was a celebration of afternoon delight in which three upper-crust MILFs pictured in the throes of self-congratulatory sensuality, pleasure one another in a sumptuously appointed living room. Foliage rustles against a paneled window and an immaculately wrought tea set occupies the foreground. Another work in a similar vein, The Conservatory, features an erotically abandoned nocturnal music practice with plenty of middle-aged spread spilling out of black lace lingerie, and clitoral stimulation tastefully concealed by skillfully rendered folds of drapery. These paintings verge upon the grotesque; they are neither aesthetically inviting to the viewer nor sympathetic to the subject, but they are provocative and they hold one’s eye.

Women of a certain age have long been Currin’s special province. Women, as he put it in a well-circulated quote that got him into a lot of the right kind of trouble, “caught between the object of desire and the object of loathing.” Women like the graying dowager in The Old Fur, who opens a fur coat to reveal a “well-preserved” body, while taking a wistful sidelong glance. Many of Currin’s women sport these wistful expressions, as if casting a backward melancholy eye at the pleasures of their youth.

It is easy to imagine Currin smiling to himself as he works, tickled by the nervous laughter his subtly incorrect depictions of the cultured classes are likely to induce in the beholder. His stance of sardonic ambiguity makes people a little uneasy, but he never lays it on so thick—the paint or the premise—that one can tell exactly where he’s coming from. He never quite crosses the line into caricature, though he comes close with a painting called Hotpants, which resembles a Norman Rockwell composition. It’s the one work in the show that features men, if you can call them that. A gauzily-painted ponce in tight shorts primps in front of a full-length mirror, while a similarly attired tailor fusses over him. The absurd vanity—and vulnerability—of those whose wealth has inoculated them against reality is often captured by Currin, as in the treacly Dogwood Thieves, wherein two blithe blondes bedizened in sun hats, ribbons and flowers luxuriate in stolen moments, blissfully impervious to worldly concerns.

A different kind of awriness pervades each painting. They are all a little “off’’ in one way or another, enough to make one wonder what’s “going on.” In Flora, a diaphanously-negligéed blonde reclines over a basket of fruit while disappearing into the corner of the painting at an angle that throws the viewer off, while Big Hands appears to be a straightforward portrait of an attractive blonde, until one notices her thick masculine arms and hands. And what’s with the portrait of Constance Towers?

There are an abundance of blondes and strawberry blondes on display, but the brunettes steal the show. Here, with two paintings, Mademoiselle and The Reader, Currin further muddies the issue by playing it straight. With these simple renderings of women lost in seductive abstraction, he arrives at an arresting combination of classical portraiture and pinup art.

These works hark back to the days when portraiture was the domain of the aristocracy. Currin updates the tradition, eroticized and filled with art historical references. Whatever his position, nobody else does what he does, and the results are capable of reawakening one’s sense of wonder at what an artist is able to do by simply applying paint to canvas. Some dissenting voices might argue that such expertise in technique is wasted on frivolous subject matter, but there is no denying the power and originality of the work.

-

Mike Kelley at Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills

You have to be ready for almost anything when you enter a Mike Kelley show: a more or less conventional gallery view of objects or documents; a maze, matrix or mosaic of seemingly found or reconfigured objects; or an immersive multi-media experience of sculptural installations, with or without video or performance. Kelley’s show at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills — even more expansive than its double-compound title — was all of these things, and what felt like a post-mortem, too.

For those unfamiliar with the Superman mythology, Kandor was the home city of the child Superman and his parents, who the adult Superman rescued from the doomed planet Krypton and preserved in miniaturized form in a vacuum bottle infused with an artificial atmosphere fed and refreshed by a tank of compressed gases. The appeal of the motive (and its disparate comic-book renderings) to Kelley is obvious: its trauma or projected traumas and implicit “repressions,” nostalgia; the uncertainty and ambiguity of memory, its corruption or adulteration, and its reconstruction, reconfiguration or simply re-imagination; parallel to this, the corruption of empire and its residue; and many opportunities for thematic cross-fertilization within this mesh of cultural and psychological strands.

The first walk-through of almost any Mike Kelley show can feel a bit like a scavenger hunt. So it was at Gagosian, although visitors to the gallery were made immediately aware of the show’s immersive aspect as soon as they opened the gallery door to a pinball cacophony of sound and stepped into the dimly lit gallery. A small pile of rolled-up rugs pushed against the rear panel of one “room” of the main gallery was immediately followed by an archway through the panel revealing a shallow stage or platform painted in camouflage swirls executed in a fire-color palette, with a mannequin standing just beyond it. In the meantime, giggles and light screams pealed across the gallery spaces, overlaid with bells, chimes, hissing, rattling, and eerie echoes and reverberations. At least one source appeared to be the video projection a few feet away. A shimmer of iridescent silk drapery (also in a fiery palette) on a tall stand set off to an angle led the way to a pile of pillows and bolsters on which the viewer might recline to take in the video.

The video performance was familiar Kelley territory in Greek (or maybe Roman or Oriental) geek guise — a college seraglio. This was the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #34 — a pair of companion skits in neat reversal (“The King and Us” / “The Queens and Me”). In the first, a dark, modish lout in brown cloak and pink toga sulks and gnaws petulantly at a mutton leg (or something) while his entourage of harem ladies recline about in silk and satin sarongs, tunics and veils, coyly competing for the boy’s attention. The boy alternately spurns, ignores, or rewards their attentions and ignites their rivalries. In the companion skit, the boy — in the same costume, but clearly servile — enters with a flagon of wine or coffee to serve his “queens” and is himself ignored or teased and mocked. A second monitor and seating between the rear gallery and the new main gallery south facilitated viewing of the loopy skits. It’s something of an homage to Jack Smith — with the set’s bejeweled look and trays of pearls, beads and trinkets flung about; but Kelley doesn’t try to take it any further than his amateur cast can manage.

Before even arriving at the first and seemingly most important of the Kandor installations, it was impossible not to be distracted by the lifelike mannequin in front of the platform (which figured as a set in the videos) — to all appearances of Colonel Sanders, founder and eternal pitchman of the KFC chicken empire — inclined over a veiled lectern or pedestal, as if in readiness to pitch his latest chicken recipe. Less clear was what Kelley was “pitching” here. “Kandor 10A” was enshrined in a grotto of what looked like molded asphalt or volcanic residue (actually foam coated with Elastomer).Here, on another mound of “asphalt,” a “city” of pale yellow opalescent crystal “towers” (tinted urethane resin) clustered beneath a large glass dome connected to a tall lavender compressed gas tank standing beside it — the whole reflected against a green metal “control panel” or prop cabinet. A pair of male under-briefs appeared discarded to one side, introducing a suggestion of masturbatory fantasy.

In the rear gallery, “Kandor” exploded into a vari-colored “City 04” — a still more oriental-looking mass of crystal elements (in resin) that from certain angles had the look of perfume bottles and cosmetic jars massed over a vanity table. A wooden stairway wrapped around the “asphalt” mound to a platform that offered a better view of the emerald, ruby, topaz, sapphire, etc. “City.” Pretty — and prettier still when viewed from the clerestory window en route to the upper level gallery.There were other objects — kitsch, generic and bejeweled — both in this gallery and upstairs, all seated on their asphalt foam/Elastomer plinths; and many more iterations of the “Kandor” motive (or “Cities”) in variously colored resins — that did little to expand or elaborate its possible meanings. “Cat Head” looked like a found object — the sort of pail or container that might be used by a child for Halloween treats — but there were also generic Florence flasks on the same mound. Lab equipment for the clinical witch? Her dwarves — or gnomes — were obviously hard at some work in “Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #35” — a purple-tinted photographic lenticular representation of which hung here. In the new south main gallery, in the setting of their workshop, the “Dour Gnomes” could be viewed lumbering determinedly around a workbench – apparently forging their own demise as well as Kandor’s, which appeared ultimately to be vaporized in the video projection at the rear of the set. A snake of flattened plush remnants of their bodies, or at least their gray suits and pointed hats, coiled around cases of Corona beer in “Mexican Blind Cave Worm.”

The kitsch and Kandors upstairs were eclipsed by “Odalisque” — what appeared to be an asphalt- (foam-) covered mummy, the face hollowed out of its skull, with soot-drenched flowing hair resting on a divan or catafalque. A glass canister holding manacles or restraints was visible at the foot of the divan.

Which brings us back to Colonel Sanders (which was not even on the gallery’s checklist). His pedestal was actually a partially veiled Plexiglas box — containing yet another set and figure — miniaturized, but recognizably Sigmund Freud. That pairing raises questions about the uses of mythology — more specifically, mythologies of aspiration, their intersection with the algebra of need, and their susceptibility to distortion and manipulation. Col. Sanders’ product was greasy, crumb-laden chicken, the appeal of which is inevitably diminished in the wake of its potentially pathological sequelae. Without attempting to confine Kelley’s multi-valent mosaic to a singular interpretation, it was difficult to “escape” from the “Kandors” and their variously associated or dissociated “EAPRs” without sensing a similar pattern of ingestions and evacuations — and their ultimate pathology and futility.

-

GUEST LECTURE: Jim Shaw

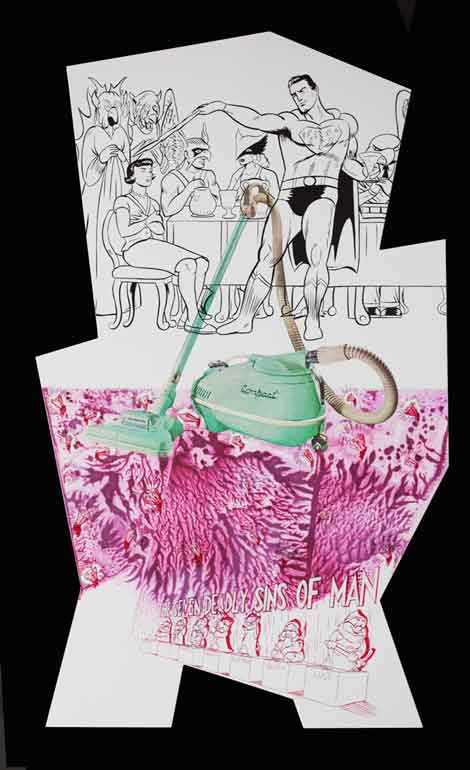

Dream Object (Irregularly Shaped Canvas: John Jones, The Martian Manhunter elevating Ignorance chicken above cartoon, “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb,” with Ad Reinhardt clip art elements as magnetic fields; mustache), 2010

Dream Object (Irregularly Shaped Canvas: Superman in Blake scene from “Comus” illustration with Compact Vacuum Cleaner; decalcomania cave of blood diamonds; 7 deadly sins; 7 dwarfs), 2010 I was working on these shaped canvases and sculptures that had printed blowups of appliances and added elements such as Expressionist drips, shirtless guys in pain, cartoon and Fauvist chickens, and cartoon elements. One was like a reduced scale version of the bone sculpture with no top or exterior thin buttresses, and the biggest had Judd-like rectangular holes and a half cylinder on the back with drips coming from it. My LA dealer came in and said he wanted them all and I said, “No.” There were elements of Bacon and the shirtless men referenced the Netter CIBA-Geigy medical illustrations and probably Longo. The shapes seemed to refer to the object on the cover of Led Zeppelin’s Presence. The Baileys had tried to get a group to buy their mansion, which was now on an island in the middle of the street in Danna Ruscha’s old neighborhood. Mike [Kelley] had also done a series of quick sketches for things like “repressed school memories game” and an issue of National Geographic with an article on Nazism in rock.

—Jim ShawImages Courtesy of Bernier/Eliades Gallery, Athens & Patrick Painter Inc., Santa Monica; Photo: LeeAnn Nickel,

Los Angeles -

A Ketchuppy Good Time

I was urged electronically to go see Dutch theater company Wunderbaum on its last night in LA at the REDCAT with no details other than superlatives (which, however, managed to get a bunch of us on that contact list out). I knew it had something to do with LA artist Paul McCarthy’s work, and the troupe was pegged as “raw” and “political.” They had been developing the work as artists in residence for several weeks at the CalArts venue.

The first two-thirds of the performance set up a reading of emails sent among cast members leading up to the evening’s performance, starting back home in Rotterdam. It seemed to be a legitimate avant-garde theater trope; an excruciating and honest look at the development of a theater piece becoming the drama. There were considerations of audience, collaboration, cultural translation, personal agendas and the illusive Big Idea. Included was the reluctant participation by a naive layperson — an attractive young bookstore owner representing the average, educated Dutch citizen — outraged by the publicly funded, arguably obscene McCarthy statue in a public square in Rotterdam. The offending work, unaffectionately nicknamed Santa Butt Plug, depicts a giant gnome holding a bell in one hand and a large sexual aid reminiscent of a Christmas tree in the other. The earnestness was amusing, and we felt let in on the joke with the “real actors,” and among people who like confrontational art. Angry citizen would come to LA to confront the artist right back.

Paul all the time, photo Wunderbaum. The email exchanges were so sniping and authentic that I dare say most of the audience was somehow merry to believe that these were actual transcripts. They wove the verisimilar with actual events, such as an L.A. Weekly theater critic Stephen Leigh Morris interview (the preview article for the play based on the interview assumed the topic of challenging Paul McCarthy was legitimate) and approaches to the artist himself. The troupe meanwhile was encountering an arts funding crisis in Los Angeles and the U.S. far more severe and intractable than the one they were in danger of losing perks from back home in a country that would support this type of somber self-indulgence. So when in the final act the whole cast (including, of course, the ingénue) exploded in an homage/parody of a Paul McCarthy-themed food and bodily fluids orgy, suddenly the whole absurd carnival was revealed hilariously. Obviously, now, the first part, with unwitting audience and media participation in the farce was a brilliantly choreographed and written play.

In the lobby afterwards, when one of the troupe’s actors was having a drink next to me at the bar, I hesitated to ask about details of the set-up, wanting to remain in the not-quite-sure what the real story was. My response was similar to the exhilaration of another favorite spectacle this year, the Banksy film Exit Through the Gift Shop. The experience of being caught up in the play of levels of narration was somehow both classical and cutting edge. These two had the cathartic effect of challenging perceptions, having my seat unsteadied by the machinations of clever manipulators, while considering notions of the arts’ role in society, and having a bloody (ketchuppy) good time.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, ARTILLERY! 5 YEARS OLD!

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, ARTILLERY! 5 YEARS OLD!