“Have you noticed, that people are still having sex? All the denouncement, had absolutely no effect.”

—LaTour, “People Are Still Having Sex,” 1991

After a long conversation with my Lyft driver about the cult he’d just joined, I walked into “The Pleasure Principle” at Maccarone Gallery—a show sponsored by Pornhub.

First, E.V. Day’s sculpture Saarinen’s Mother: a saddle-shaped, deep-sea thing, frilled like a collar, a frayed nerve or an Atlantean crown, made of devil-red and translucent womans’ underwear, resined and damp-looking, slit front and back for easy access, stretched and stellated at dozens of points by a symmetric system of monofilament lines anchored dramatically with metal eyelets in glass and holding, in the tenuous criss-cross between the slit-mouths, a blown-glass and drippy bubble-shaped bottle.

E.V. Day, Saarinen’s Mother I, 2008 (photo credit: Tom Powell)

Many sculptures arrest a moment in time, a few good ones isolate, extend and offer up for inspection what previously existed as a temporary and barely coherent sensation you might’ve seen somewhere in the black back-room of the brain. There’s a lot here—the title suggests affinities between architect Eero Saarinen (a virtuoso of the distending modernist shapes made possible by prestressed concrete) and his textile-designing mom. Even without the dripping and gloss and the thing in the middle being lingerie, the spectacle of a familiar body pulled tautly and transformed in a way that makes every part of it important and beautiful and absorbing and different from every point of view by precisions that make that tension last forever should earn this piece a place in any art show about sex.

Installation view at Maccarone: E.V. Day, Saarinen’s Mother I, 2008 (photo credit: Coley Brown)

There keeps on being sex because people keep on being alive and people keep on being alive because there keeps on being sex and there keeps being art about sex because art is always about life. But never mind all that: how do you weaponize it? What can the 2019 battlespace use Saarinen’s Mother to fight about?

Maccarone Gallery is fighting a skirmish to show that this sex show isn’t all a gimmick and that a private gallery can maintain standards and integrity while taking a big company’s money to produce a show about what that sponsor distributes. On another front, Pornhub—a company that’s even more controversial inside the porn community than out of it—is fighting to be considered a responsible corporate citizen that, like any insurance or cigarette company, can be expected to just go around sponsoring humanistic beaux-art endeavors.

Installation view at Maccarone: Trulee Hall, Eves’ Mime Ménage, 2019 (photo credit: Coley Brown)

To these ends, it’s no coincidence that the rhetoric around this particular humanistic endeavor humanizes pornography (from Pornhub’s press release:“…these artists carve out space for the profane and the pornographic, the abject and the occult, the sexual and the sexualized. The exhibit centers a variety of feminine sexual subjectivities, decoding erotic pleasure amidst a visual culture so stifled and diluted by concerns of appeasement.”) or that it comes at a time when the porn industry is being shaken up by a variety of border wars most people don’t care about—including SESTA/FOSTA legislation, the rebranding of anti-porn laws as “anti-sex-trafficking” and “anti–sex slavery” and the chilling effect around sexual imagery created by the fact most public conversations about sex or anything else now take place on privately owned social media sites with no clear rules about what is and isn’t offensive and an ever-expanding desire to keep China happy.

Installation view at Maccarone: Annie Sprinkle, Anatomy of a Pin-Up, 2006; Doris Wishman, Satan Was a Lady, 1975; Come with Me My Love , 1976; Let Me Die a Woman, 1977 (photo credit: Coley Brown)

In this phase of the Kitchen Wars Saarinen’s Mother—being sexy, abstract and figurative, avant-garde, subtle, relatively new, made by a woman, and very good—is a high-carbon vg-10 Kasumi Damascus knife fresh from the sharpening block. Easy-to-grasp, contoured for use, and sharp enough to make you forget that the real reason this wonderful thing got made wasn’t to help you fight with anyone, but to slice things up so you can eat them and so be happier afterward.

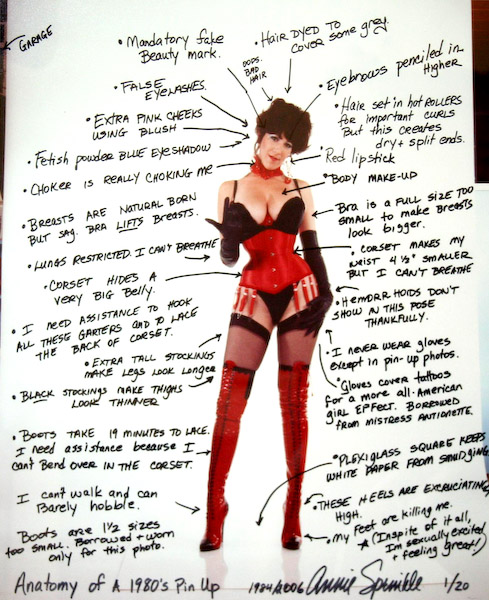

Compared with this, Annie Sprinkle’s Anatomy of a Pin-Up, also present at the Maccarone show, is the can of mace by the back door—an object purpose-built for personal protection. It is happy to take a side in a cultural brawl—its entire purpose is to take a side in a cultural brawl. It’s a photo full of annotations pointing out all the stagecraft and sleight-of-hand in a pre-Photoshop sexy pic, and has an unambiguous message: Pin-ups are artificial constructions, at best tangentially related to reality and to real female desire.

Annie Sprinkle, Anatomy of a Pin-Up, 2006

Around the corner are pin-ups. Classic mid-century pin-ups, by-and-of Bettie Page, and Bunny Yeager. Any message Yeager (whose how-to books include “How I Photograph Myself”) or Page might’ve intended is less The Message than the message sent by the fact of their inclusion: Pin-ups and porn can be high art and its authors—which include women—can be credited as artists. Around the corner from those are super-cut collages by a contemporary video artist of appropriated porn films—authors uncredited. Across from those are older porn films directed by Doris Wishman, including two she apparently didn’t like because they had explicit rather than implied sex and which she therefore denied making before she died—both feature Annie Sprinkle, author of the pin-up deconstruction.

Bettie Page (attributed to Irving Klaw Studio), Untitled, n.d. (photo credit: Henry Feldstein)

In aggregate, these pieces can’t easily be pressed into service as propaganda—they tell no coherent tale together because they weren’t meant to. The subjective experience of sex during a single human’s life is not about what we share universally—it is about peculiarities shared by one person and a highly select group of other people they ended up in bed with. Sex is a subject for a novelist, not a pamphleteer. Pretending artists are attempting to speak to the universal about these most private parts of themselves only results in familiar and reductive cliches, where the only important piece of information about the art is the name on it: straight men’s art is always assumed to be about obsession, straight women’s art is always assumed to be about media images, queer artists’ art are always assumed to be about queering the art space, the art of the marginalized is assumed to be primarily an attempt to get unmarginalized, the art of the powerful is presumed to be clever self-satire—even if all of them just painted the same boob. For the most part artists accept these cliches because they at least attract attention—and attracting attention is how they can afford to eat.

Installation view at Maccarone: Bettie Page and Bunny Yeager photographs, n.d. (photo credit: Coley Brown)

Art is not obliged to make statements—it is free to deal in fictions, poetry, thought experiment, reportage. As a result our public square is full of artworks about sex and sexual possibility that are interesting, inventive and useful while our ability to talk about them is still held up at an intersection miles behind.

In a standard press release about art, you often get the feeling that some stoner’s desire to paint circle-people or stack colored sponges has been dressed up by a gallerist or critic with references to Foucault and Adorno, but shows about sex inevitably invert the formula: the art is smart and informed by real experience, the talk is dumb and informed by fear of what will be said in response. The dreaming individual can say more about sex than the cautious collective. All the dialogue can do is approve (liberating!), disapprove (don’t @me!) or look nervous and go “This raises issues.”

Genuine, unperformative descriptions of what good art about sex does to audiences remains thin on the ground, because few critics are in a position where they can risk admitting to what excites, surprised, or alarms them. For anything remotely sane you have to find someone not just smart but unassailably successful—like Zadie Smith, who writes about being shocked by her initial encounters with Crash, JG Ballard’s novel about car-collision-fetishists, as a college student in the ’90s:

What was I so afraid of? Well, firstly that west London psychogeography. I spent much of my adolescence walking through west London, climbing brute concrete stairs—over four-lane roads—to reach the houses of friends, whose windows were often black with the grime of the A41. But this all seemed perfectly natural to me, rational—even beautiful—and to read Ballard’s description of “flyovers overla[ying] one another like copulating giants, immense legs straddling each other’s legs” was to find the sentimental architecture of my childhood revealed as monstrosity…

Bettie Page (attributed to Irving Klaw Studio), Untitled, n.d. (photo credit: Henry Feldstein)

She describes eventually coming to terms with Ballard’s vision some time after the Britain’s conservative Daily Mail went to war on David Cronenberg’s film adaptation of the novel:

Crash is not about humiliating the disabled or debasing women, and in fact the Mail’s campaign is a chilling lesson in how a superficial manipulation of liberal identity politics can be used to silence a genuinely protesting voice, one that is trying to speak for us all. No one doubts that the abled use the disabled, or that men use women. But Crash is an existential book about how everybody uses everything.

What strikes me reading Smith’s essay on Cronenberg now is that her desire to intellectually justify the book seems almost as old-fashioned as her initial outrage at it. Who justifies anything anymore? We don’t keep works of art around because they deserve to exist, we keep them around because they serve someone’s purpose. Everybody uses everything.

The 20th-century cycle of shock-censor-justify has ended not with a truce that raises sexual imagery above suspicion, but with one that lowers all art production to the level of a kink. The contemporary moral panics aren’t about what’s in the art, they’re about how much all this frivolity costs and who benefits. It was once shocking that someone of talent might want to portray a glistening nipple, it’s now only shocking who got paid for it. The outrage is about how power is being deployed, not how creativity is. The morally fraught question “What is in this art?” (suggesting it might be something unknown) has changed into “Which side have you thrown in your lot with?” (suggesting every image has a predetermined place in a hierarchy of Right Ways and Wrong Ways To Represent).

Installation view at Maccarone: Laurie Simmons, Color Pictures/WIlliam Baziotes, 2009; Color Pictures/Walt Disney, 2009; Renee Cox, Garter Belt, 2001 (photo credit: Coley Brown)

The most offensive, antisocial thing about sex is the same thing that’s most offensive and antisocial about art: the difficulty of exploiting it. No matter how much we advertise it, the experience of the encounter remains individual and private. Yet, people insist on doing it anyway.

0 Comments