“Why do we call Deutschland Germany?” Kischnec asked his friend Linda, one of the passing chickens dangling from the conveyer belt. “It’s not like it’s hard to say: DOITCH-londt. What’s the fucking problem? Same with other countries. But I imagine you know more about that than I do.”

“ . . . ,” said Linda.

Kischnec ran the factory, or so his boss told him to say, in case journalists broke in and asked. Mostly Kischnec tended to the belts, to the bird bins, to the hooks and cables, gears and blades. Since the one-year mark, in late January, it had been company policy that all employees wear matching wigs—hand-crafted wigs of exceptionally fine pale yellow synthetic fibers, rendered almost mullet/almost 1970s assistant manager at Steak ’n’ Shake, yet neither; impeccable fibers, lightly varnished into precisely layered curves of interdependent wisps.

These mandatory wigs were all the rage in Wyoming, a state with two United States senators and the same number of residents as you passed today on your way home from work.

To accommodate his wig, Kischnec had buzzed his hitherto mighty russet Afro down to the sprouts, a look he’d eschewed since grammar school, before his middle-school basketball coach encouraged him to grow out his hair to appear more intimidating, or at least more distracting.

Atop the wig, Kischnec wore another mandatory accessory: a blood-red Chinese trucker hat with large white uppercase letters embroidered across the front:

MAKE

<INSERT YOUR COUNTRY>

GREAT

AGAIN

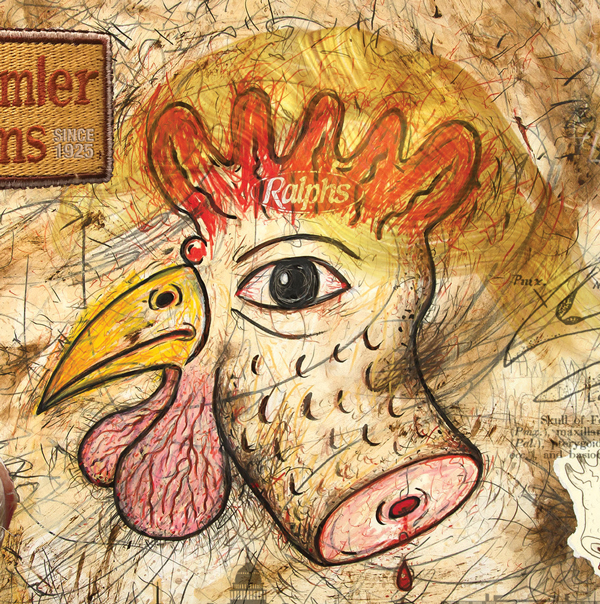

Illustration by Jeffrey Vallance

Beneath the hats and wigs, while Kischnec and his colleagues on the factory floor wore white hazmat suits with turquoise aprons over dungarees and company T-shirts, their boss, Brainard Wehrf, wore what everyone called the chicken jacket—a soft suede, two-tone, vintage-style baseball bomber jacket with the Himmler Farms logo embroidered on the back. Beneath the chicken jacket, Wehrf wore a white button-down shirt and either a red, black, or red-and-black tie. On the front of the chicken jacket, where a breast pocket might otherwise go, Wehrf had paid his gardener’s 9-year-old paraplegic daughter $8.75 to embroider four uppercase letters similar to those on the trucker hats:

WPWW

“That’s more than two bucks per letter,” Wehrf told the girl, whose name he did not know. “If you finish in an hour, that’s more than what most of your people make.”

One late afternoon in the break room, Kischnec asked Wehrf what the letters stood for.

“You’re an adult,” said Wehrf. “Look it up online.”

“All right, then.”

“Kischnec—what kind of a name is that, again? I know you once told me, because I know you’re not a Jew, but I can’t remember. If not for the nec, it could almost be German.”

“Slovak,” said Kischnec, “on my father’s side, and Mom’s people hailed from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, way back to the 13th century. Remember? We figured out we had relatives who maybe worked for the same luthier in Westpreußen in the 17th century?”

“No,” said Wehrf. “I have no recollection of that at all. Pretty sure I don’t have any Hungarian in me.” Wehrf allowed fruition of a minor hoot and let out a chuckle.

“Huh,” Kischnec replied to the hoot-chuckle, raising his eyebrows and nodding.

“Meaning what?” Wehrf snapped back. “You think I’m part Hungarian?”

Kischnec saw WPWW on the optional chicken jacket.

Wehrf saw GREAT AGAIN on the mandatory trucker hat.

“I haven’t really thought about it,” said Kischnec. “But now that you mention it…” He stood, smiled at his boss—in such a way that his boss would hopefully know that the Hungarian implication was a facetious one, and not the sort of thing that might lead him to fire Kischnec, leaving him to die penniless and in agony and madness on the street—and returned to the factory floor. —Dave Shulman

0 Comments