“SHE WORLD” invites us to embark on a dark journey through the mingled lives of a group of women of a past generation. Ursula Brookbank’s archive of objects—once belonging to these unrelated women—is installed in deliberate and moving vignettes, creating a collective diary as a monument to their shared and individual experiences of female life in the 20th century. The viewer is quickly struck by how strongly the cards were stacked against them.

On another level is the bone-chilling sensation of fear and unease that “SHE WORLD” evokes. From the first moment, the viewer is thrown off guard, entering through the gallery’s rear pew room—a space often serving as a theater for video, here functioning as more of a lobby. A low red pedestal houses a collection of odd objects propped on random stools and music stands: an ugly table lamp, a pelvic X-ray mounted with a clothespin and sprouting rusty curling wires, a jar of hairpieces. The soundtrack (by Emily Lacy) emanates from this room and sets the tone for the experience. Music and vocals, heavy on the reverb—suggesting echoes in some vacant and lonely place—include schmaltzy organ tunes and ’20s dance hall music, like the kind in the background of the bar scenes in The Shining. Past and present coexist in an eerie shift.

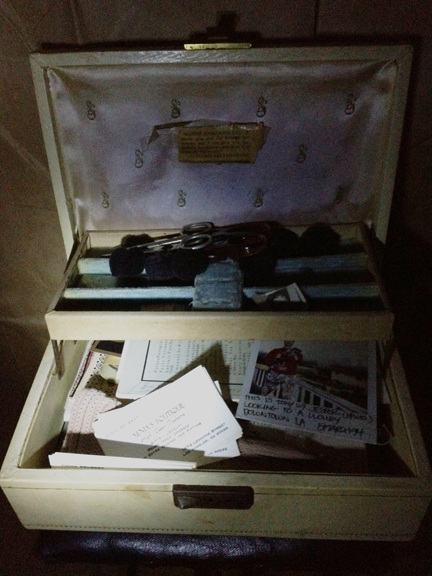

The viewers receive small flashlights to navigate the next two rooms, which have been completely darkened, intensifying the sense of trespassing into an intimate experience with absent women. One wall houses an assortment of needlepoint samplers, including a homely oval image of a horse’s head. Satin boxes designed to sort and display jewelry or toiletries contain instead plastic grapes, doorknobs or a sheet of buttons. In the rear room, a creepy carving of white roses and gold leaves, a massive spray, is mounted on one of the pillars, suggesting someone’s bad taste morphed with an aura of funerary accoutrements.

The contrast of seeming randomness—objects piled haphazardly on the floor, or perched in the rafters—with carefully and precisely arranged displays, such as a table bearing pieces of shoes, lacings and rotting bits of soles almost assuming the significance of holy relics, signals clear dysfunction and bittersweet poignancy.

A collection of papers anchored with specimen pins documents Brookbank’s research into the lives of the women to whom these objects belonged, often chronicled in obituary format, along with an inventory of the objects and related pictures. These strike a rather clinical note. Also in the mix are Brookbank’s shadowy self-portraits, dark and haunting veiled faces and torsos, which relate closely to her video work and suggest a mingling of Cindy Sherman and Matthew Barney.

By transforming bits of yarn, buttons and soap dishes from kitsch into icon, Brookbank makes a strong case for the power that objects themselves may yield. As symbols for the otherwise forgotten lives of women, they convey a collective energy that becomes hypnotic and gut-wrenching in this remarkable environment.

0 Comments