A master of text-based montage working in the traditions of Fluxus, Concrete Poetry and Dada, Tm Gratkowski pays homage to artists like Kurt Schwitters and Tristan Tzara, whose complex word/image juxtapositions were imbued with cultural critiques. Trained as both an artist and architect, Gratkowski’s carefully constructed then excavated surfaces comprised of magazine pages and clippings share architecture’s structural intricacies.

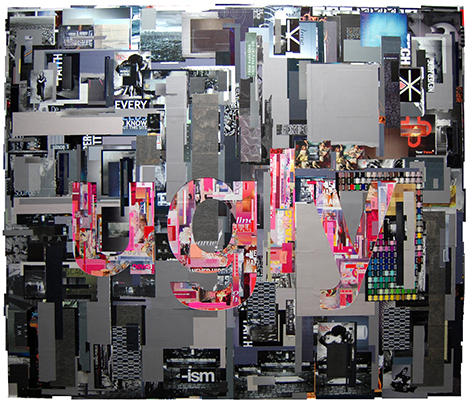

Layer upon layer of torn, cut and printed fragments as well as whole pages culled from myriad magazines are adhered to the surfaces vertically and horizontally, creating an ordered chaos. Random words emerge from the eye-pleasing clutter forming open-ended quasi-narratives across the compositions. Traces of color are scattered through the otherwise black, white and gray palette of printed ephemera. Three large works—7×9 feet—Good, Bad and Ugly (all 2014) dominate the front gallery. In each, a single word—good, bad or ugly—has been carved from the thick collage to reveal a layer of color that pops from the surface below. While these words suggest a way to interpret the piece, they also provide an opportunity for the viewer to question the work’s value—good, bad or ugly—based on the content and context Gratkowski provides within the collages. The works are incomplete puzzle fragments that beg to be completed. As the viewer finds a rhythm in which to understand the disparate fragments, the pieces begin to cohere.

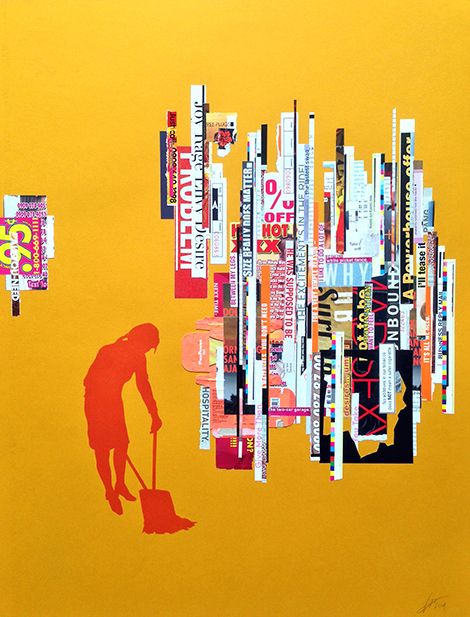

In addition to striations of text, figurative silhouettes are integral to his series of smaller works on paper. Most of the black or gray figures in these collages—seemingly derived from news imagery—are engaged in some action: walking, sitting, sweeping, shooting, boxing. One might expect these depictions to be supported by the texts that surround them; however, Gratkowski’s works are never illustrative. In Power Envy a female silhouette spray-painted in an orange hue onto a mustard-yellow background sweeps invisible items into a dustpan. Her activity is not explained by the collaged texts that surround her. Snippets of text extracted from women’s magazines and pornography read as slogans: Joy Rage Envy Desire; Size Really Does Matter; He Was Supposed To Be; I Like To Do a Lot of; Perfect White Picket Fence. While the cut-out texts can be seen as the debris the woman is sweeping, they remain found poetry fragments that never coalesce as a readable whole.

The silhouette of a crouching woman in Cinnamon Crash presents a similar disconnect. The readable text within the figure is presented in contrast to the undecipherable collage above her, metaphorically the weight of language. The relationship between the silhouette and its text, like the relationship between the words within the overall piece, is either visual or purely happenstance.

Gratkowski delights in creating complex visual environments from found language fragments. The works are complex and compelling amalgamations of ubiquitous source material carefully montaged together. They become contemporary examples of concrete poetry that offer rewarding surprises to viewers who delve into making meaning from jumbles of fragments.

Yea! Great mag for covering Tm Gratkowski