The standard museum retrospective brims with artworks supported with biographical and thematic information. “Roy Lichtenstein: Pop for the People” brims with biographical and thematic information supported with artworks. Neither the selection nor installation of the artworks allows those works much room to function autonomously. The art here does not speak for itself, but for a narrative about their maker and the circumstances of their invention. The retrospective functions less as an art show than it does as an artist’s biography.

Fortunately, even as it harnesses the seventy-odd artworks to a story about Lichtenstein himself and the emergence of Pop Art, “Pop for the People” re-enlivens them, setting them into a kind of meaningful motion. In the two galleries devoted to the show, the variety of objects and subjects “come alive” the way artifacts in a non-art museum exhibition do. Does this reduce a Lichtenstein painting or print or multiple object or even magazine cover design to the status of a dinosaur bone or political lapel pin? No; the installation is not nearly that iconoclastic. The artworks cannot be seen outside the contexts the curation gives them, but they can still be admired. Their didactic role, if anything, animates them by allowing them to escape the art-history books and the auction-house websites.

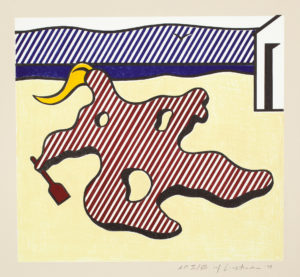

Roy Lichtenstein, Nude on Beach, from the Surrealist Series, 1978. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation. ©Estate of Roy Lichtenstein / Gemini G.E.L.

Animating artworks by re-contextualizing them is certainly appropriate in Lichtenstein’s case—not only because of his reliance on cartooning as both source and method, but because re-contextualization lies at the heart of his preoccupation with what we now call “visual culture.” Further, his style has become a cliché of modern artistic practice and is itself in sore need of revitalization. a show like this, long on side story but short on artsplaining, does wonders for our grasp of Lichtenstein’s thinking and its results. Sure, “Pop for the People” relies on a lot of wall text, and even on photograph, but the artworks, as meaningful presences, are enhanced rather than diminished by this arrangement.

The smaller of the two galleries is devoted to Lichtenstein’s giddy but respectful tropes on other art and artists, a signal practice of his once he grew past the comic strip appropriations. Several sequences vie for attention here, all of them more or less familiar to art folks, but it’s good to see those sequences again. Alas, the gallery is dominated by a made-for-show reconstruction of a large Lichtenstein painting based on van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles—an unnecessary for-the-kiddies stratagem that, especially given the real estate it occupies, is the only full misstep in the rather crowded exhibition.

Not everything is likely to jostle even the best informed artophile’s memory. Some of us will discover something new among the later works represented (including several immense, even to-scale room prints and paintings—clearly the inspiration for the van Gogh room gimmick). Others will find early editions in odd formats, such as the felt banner hung at the show’s main entrance. (The show portrays Lichtenstein as a pioneer of the multiple edition.) And details on even the most basic Lichtenstein stuff, such as the origins of specific comic-book images, are spelled out with refreshing clarity.

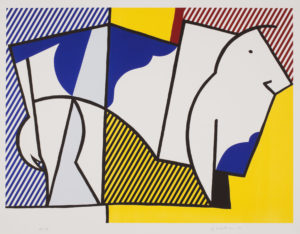

Roy Lichtenstein, Bull III, from Bull Profile Series, 1973. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation. ©Estate of Roy Lichtenstein / Gemini G.E.L.

The effect is to answer casual visitors’ questions about an artist they’ve always known about and to fill in gaps in art-oriented visitors’ more refined, or at least more copious, knowledge. Further, the accompanying documentation plays up aspects of Lichtenstein’s life and times not usually foregrounded—his Jewishness, for instance, and his reliance at critical points in his career on the support of co-religionists in the comic-book and the gallery industry; or his connections to Los Angeles (principally through Gemini G.E.L.); or his lifelong love of jazz. Clearly, these topics are brought forth because of their, well, topicality (i.e., the Skirball’s role as a Jewish museum in Los Angeles). Such themes don’t seem central to Lichtenstein’s oeuvre, but they comprise some lively footnotes. So do Kamali Washington’s jazz-ensemble compositions piped into the main gallery, building as they do on the kind of post-bebop Lichtenstein favored when he was a young man.

“Roy Lichtenstein: Pop for the People,” isn’t an artist’s retrospective, but an artist’s biography in exhibition form—not a survey with a catalog, but a catalog in a room. (No actual catalog accompanies.) This approach is perhaps more appropriate for a cultural museum like the Skirball than an art museum per se, and you wouldn’t want it to supplant the traditional retrospective survey. But here, however, it successfully tells the story and, in the process, engages the art without swallowing it.

0 Comments