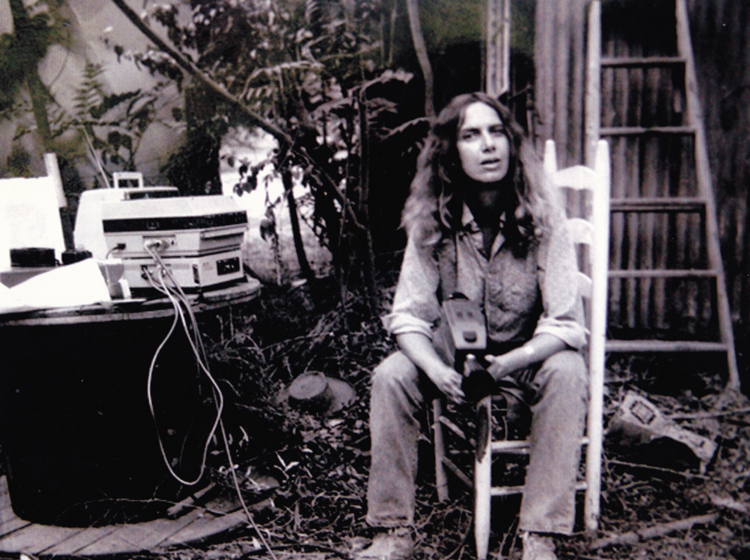

In the late ‘70s, I would carry the Sony Portapak for my artist stepmother, Rabyn Blake, across muddy fields in Southern France as she filmed a shepherdess whose name sounded like “leg of lamb” in French, or shot shimmering vistas of Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire. (She had maneuvered my father into taking his sabbatical in Aix-en-Provence, I now believe, so that she could bathe in that light and landscape and have her own way with it.) For those who never experienced the early days of amateur video cameras, the “porta-“ aspect of the pak was a manner of speech. The thing weighed about 30 pounds and was much bigger and less wieldy than a breadbox. It was inspiring to be in the aura of her intense creative energy and to see through her lens in the videos she created in that period of ferment, but I didn’t realize back then just how seminal and groundbreaking (literally: read on) her work and that of other artists working in the nascent form was.

Blake moved to Southern California from Virginia for graduate school in French literature and stayed to become an early adapter to the earthy/arty/hippie community of Topanga Canyon in the ’60s. Artists such as George Herms, Wallace Berman, Russ Tamblin and Llyn Foulkes were in her milieu. It was during her years at Otis, though, that her passion for video switched on. Another fellow Topangan and art photographer, Mark McCarty, originally introduced her to the video camera and taught her the basics of using it.

Blake, now close to 80, still has a youthful air with her long wispy waves of hair and a lean frame, her body moving somewhat more slowly than her mind these days. I met with her in her Topanga home and spacious studio tree house where she continues to work as an artist, active also in alternative healthcare and local politics. “Everything was possible,” she enthused in her still honeyed Southern lilt over tea. “The element of time of flux that was offered was part of this wonderful insignia.” In hindsight (the only way many of us will get a chance to see these works, as the tapes turned out to be quite fragile and the formats changed so rapidly), the medium and the tools seem clunky and weighted with extra-formal glitches (the horizontal lines and the TV set framing), a kind of sci-fi vision of the future from the past. And yet these are precisely what mark the work and capture a moment emerging from the fertile imaginations of people at the time grounded in the elements that artists have always used: light and the materials at hand. “The video artists were coming out art schools: CalArts, Otis, from all forms. And [most of the faculty] didn’t like it,” Blake explained—with notable exceptions like John Sturgeon. They were still entrenched in the categorizations/canonizations according to traditional forms: painting, drawing and sculpture. “It didn’t fit. Their reaction was, ‘What is this bastard thing?’” But there was no specific practice or discipline that video art emerged from. It was, in a sense, she continued, its own genre: “Just video, baby, just video.”

Los Angeles came to be recognized as a locus of video art with the Long Beach Museum as important curator, the “Vatican” for video, as Blake put it. They had the equipment available to check out when few people actually owned it. Artists were drawn to the immediacy, as well as the “luminosity of video as opposed to film which is projected through a light source,” David Ross, then curator of the museum and more, noted in the program for the Southland Video Anthology 1976–77. “He was the heavy-duty video curator at the time,” said Blake. (Ross later became director at the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Whitney.) Blake’s work was shown in the Anthology alongside that of John Baldessari, Chris Burden, Paul McCarthy, Suzanne Lacy and Lynda Benglis.

Women were represented more equally in video, perhaps as the absence of master canon offered a kind of freedom coinciding with that era of feminism. Initially, though, traditional venues were not available. Experimental film houses such as the Anthology Film Archives in New York—curated from 1974 to 1982 by Shigeko Kubota, video artist, Fluxus member and wife of Nam June Paik—showed video artists. Kubota showed Blake’s work and her own, as well as her husband’s in those years. Video was shown in other nontraditional venues since museums and galleries weren’t sure what to do with the upstart form originally. Another local venue was LAICA (Los Angeles Institute for Contemporary Art) in Century City. LA’s own storied WET magazine (an unclassifiable project nominally organized around the concept of “the art of bathing”) featured Blake’s mudpool video stills and events in several issues. Video stills were another way to flatten and show work, though there was no substitute for viewing the three-dimensionality that was video playing on a monitor in a room.

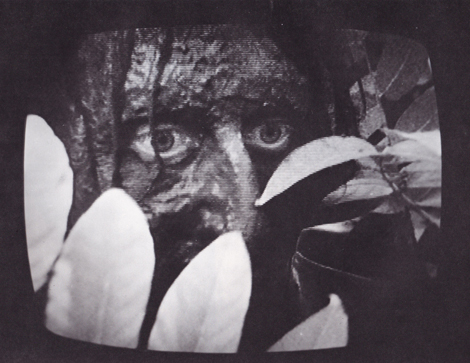

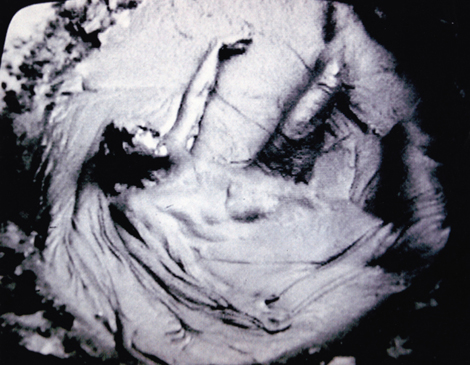

Blake’s seminal video, “Mudpool,” came out of many artistic and environmental concerns. With the help of her artistic assistant David Allen, she dug a hole in the ground at her Topanga home and invited artists, family and friends to experience the sensual heated churn and perform for the camera or witness the moving sculpture people became in the actual mud and then reproduced as such on video works. Filmmaker Shirley Clarke, David Ross, dance troupe IDEA and many others attended events such as the “mud matinee.” Of her mudpool she said, “As it happened, the flux of mud, light and figures created an illusion that reads on video as a fusion of painting, sculpture and dance. Painters see painting, sculptors saw Ghiberti, and especially Hellenic bronzes, and embarrassment of Rodin. It was womblike, sensuous. You could project anything at all on to this imagery.” The dancers were like a Bosch vision out of the Garden of Earthly Delights. As she told WET in her feature: “The mudpool was conceived as a sculptural environment incorporating us as animate sculpture; a social earthwork.” The 8-minute black-and-white video featured male and female figures “rolling and coating themselves with the silvery stuff like sculptures out of the primae materia, undifferentiated yet fully formed” (from the Southland Anthology catalogue). The soundtrack for that version was otherworldly whale song conjuring primordial stirrings and creation.

Blake has played with the conflation of earth/Mother in much of her subsequent work. She crafted bread-like foam babies and fetuses for her Feedus series, and has worked in recent years on tiny mythical creatures sculpted in porcelain and assembled into exquisite and dreamlike landscapes, shown last year at Beyond Baroque and in an earlier collection at OCCCA’s “Echoes: Women Inspired by Nature” show in 2007. Her environmental and anti-war activism has also been reflected in works in painting, sculpture and assemblage.

The Getty now owns two of her video pieces, “Mudpool” and “Pease Porridge,” a nightmarish vision into the psychic torments of motherhood/childhood that seemed to have influenced David Lynch. And while she might deny it, she was hot shit at Otis and influential not only to emerging artists at that time, but also to mentors and professors. I think she still is.

Rabyn Blake Sercarz: Most exceptional woman, earth-caring warrior of love, great humour and brilliance, amazing friend, trusted ally, artist beyond description. Yes, this is my hero, my Beloved Godmama, forever with me in my Heart, and I am sending her love wherever she is now walking, resting, relaxing, preparing her concoctions in Topanga, as I wander in Scotland with our Celtic ancestors, sending powerful ancient love-medicine, Claire

Rabyn Sheldon Blake was the first woman artist I showed at

LIMA Gallery in Culver City…with Peter Shelton.

(It stood for Look In My Art Gallery).

I bathed in her TOPANGA mud baths knowing that her art career represented an example of fierce idealism and feminism combined, an emerging concept in the late 1970’s. Diane Buckler was another ground breaking artist following that path in an underground women’s art movement emerging in that same decade of cutting edge conceptual art. . I helped promote their careers at LIMA Gallery and designed Rabyn’s advertising in WET Magazine. A small step for women artists…a big step for womankind. I later designed whole issues at L A style Magazine dedicated to the Los Angeles art world as Art Director there in the late 80’s keeping my interest in women’s art at the forefront of the content. Rabyn Sheldon Blake is a guiding light for all artists but especially to me as I was as a fellow graduate student of hers at Otis Art Institute in a time of accelerated change in the art world. I’m proud and honored to be her friend now.

Love to know this history about such a wonderful warrior woman. I knew she was an artist and yet has no clue that she was. Ground breaker – although it doesn’t surprise me one bit. So interesting as I have been thinking about Raybn a lot lately. Thank you for this eye opening piece!