Meeting Marycarmen Arroyo Macias in MexiCali was a fortuitous event; she lent me her camera in a pinch to photograph potential performance locations for the MexiCali Biennial 13, in which we were both included. When I asked about her work for the show, she told me the museum was concerned about her plan to install raw meat in the gallery, for fear it would attract rodents and insects.

It wasn’t until I encountered Tomad y Comed… (2012) at the Vincent Price Art Museum (a pig blood version, oxidizing into a rusty brown) that the embodied impact of Arroyo Macias’ materials hit me. Her symbolic and literal pound of flesh called up an array of political, gendered, economic, religious and social problems around Mexican identity. Her use of language is a consistent theme, and the selection of words from a deeply ingrained Catholic ritual further complicated the installation. “I associate cannibalism with religion here in Mexico,” she said. “We have a deeply held belief that we must sacrifice our happiness, our lives, our loves—to help others, especially our families. I don’t agree with this idea of sacrifice, which is more powerful and constant with women; but other kinds of sacrifice happen for men, and often through religion, the problem of Catholicism.”

Arroyo Macias’ family resides in Tijuana, Puebla, San Diego and Mexicali; she travels between these regions and addresses their disparities in her projects. For the Puebla Biennial she created Diccionario Spanglish, a flag of red and green “words in our common language.” Each word or phrase has various degrees of usage and familiarity depending on the region, from Frontera to El Centro. By playing with their meanings, definitions and recognizability, Arroyo Macias also plays with the shifting identity of being Mexican and how that identity manifests through language.

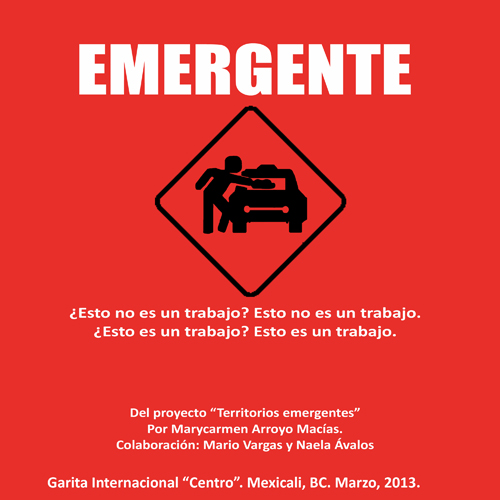

Arroyo Macias connects strongly with painting as a medium; her most recent project takes the famous Magritte work Ce N’est Pas Une Pipe (“This is Not a Pipe”) as inspiration. Emergente is both an investigation and intervention exploring the economic and political impact of Mexico’s franeleros, or window washers, who congregate around the border and offer to wash the windshields of autos stuck in la linea. Arroyo Macias interviews these workers on whether their labor is designated “illegal,” and on their defamation by merchants who often suspect them of theft. She trades a fresh franela to the workers for their used dirty franela, and will sew the soiled cloths together into a large quilt-like piece, to be labeled with the crossed-out saying Esto no es un Trabajo (“This is Not a Work”). “This situation has been created from the conflicts around education, economies and immigration, political problems that come from this kind of labor. We need to accept that this work is happening out of necessity; the causes that create it are in control of the government,” explains Arroyo Macias. She intends to collaborate with Mexican video artist Karla Paulina Sanchez to document her exchanges with the franeleros and the conditions of her labor. “My first language was painting, “ she said, “but I ask for help and have contact with people in using media, although I like to use objects in my process… political and economic paradigms are a part of my work, continuously.”

0 Comments