The figures are in motion, contorted, double-jointedly bending over themselves—so confused with playing multiple roles that a single, consistent identity becomes, at best, elusive and in its most virulent form, theater of the absurd; a brand of schizophrenia that incessantly whispers (in your voice) the same toxic message. In this scenario self-effacement becomes self-defense. It is no wonder. Blackness in the United States has always been considered an affliction. From the criminalization of presumed equality—bumptious conduct—it is clear that parity is an absurd notion. Uneven punishment permeates not only criminal justice but also primary school. In his book, The Protest Psychosis, Vanderbilt professor Jonathan Metzl demonstrates that being black can drive one crazy—at least in mental health diagnoses. He demonstrates a clear shift where, beginning with the Black Pride movement in the 1960s, the medicalization of dissent skewed schizophrenia heavily away from white housewife toward black radical.

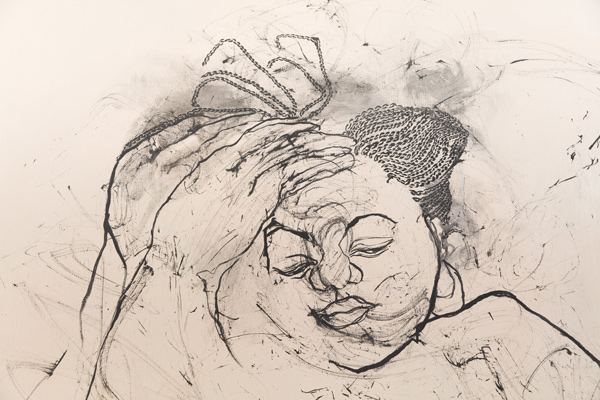

Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle The Evanesced #24, 2016, © Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, 2017, Courtesy of the artist and Jenkins Johnson Gallery

There are seven large drawings in this exhibition, on buff-colored canvas. The 100 sketches included are also buff. So are the walls, a clever bit of museum design that gives the illusion that the exhibition is in the process of disappearing. These women are disappearing—the images are variations of the artist herself who is revealing and illustrating our willful amnesia. The title of the exhibition, “The Evanesced,” refers to the disappearance of black women in our culture, historically and in recent memory. Hinkle’s elegant ink line drawings—calligraphic, rubbed away, then redrawn—refer specifically to the murder of black women by the “Grim Sleeper” serial killer, to whom it is widely suspected that the Los Angeles police devoted less investigative attention than if the victims had been white, as well as the recent deaths of black women at the hands of police across the nation. While the 100 small sketches have a vibrancy that mimics animation, it is the seven larger works that anchor the narrative. Each is titled in a synonym for obscuration—though six-feet tall and four-feet wide—and none of the women meet the gaze of the viewer (lest they be accused of reckless eyeballing).

Dispersion is three-breasted and kneeling, twisting away from us as her paired hands obscure her head. Amnesia arises from a puff of smoke and disgorges a miniature woman who may be giving birth. Eclipse is in motion, two-headed and four-legged, and her braids rise like smoke. Uproot is a figurehead floating above mountains. Her breasts are detached, her hair cropped close; she is a sign in the sky, a deceitful promise. Blackout is weighed down by a thicket of bad hair; she is an anti-Rapunzel, impaled by her most distinctive trait. Dissolve tumbles, head down, her hose wrinkling down to coils around her upended and torqued calves, enveloped by her oversized hips and breasts. Blemish is masked and kneeling, her face hidden by the only color in these works, a dazzle of complements, drawing attention yet hidden.

For the seven sisters in this sorority, the hazing never stops.

0 Comments