The idea of using film to expose natural forces other than light remains a curious pursuit. Jeremy Bolen is one of a few artists who have taken the sacred medium and, as innovators such as Fontana, Klein, Duchamp and Broodthaers have done, subjected it to varying forces of wind, earth and water.

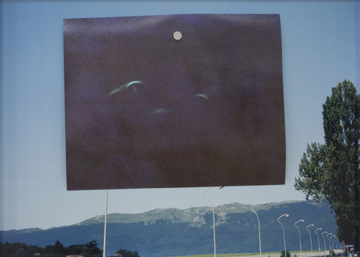

In his recent exhibition “Cern” (all works 2012), Bolen’s version of elemental bombardment is unique in that his film is put into direct contact with the environment near the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Geneva, a massive particle accelerator used for advanced research. He investigates the steel structure of the CERN compound itself, as well as earthen and liquid fields in the surrounding area of Lake Geneva. Some, for example his “350 feet above the Large Hadron Collider” series, are displayed in the gallery with tiny circular magnets to attach, atop the 5×7 images of the site, other photographs with traces of the site-specific dust, pollen, grass and water stains that adhered to his photographic negatives.

The exhibition’s title refers to the environment of the site but may also illuminate the endangered condition of explorative scientific research. (Not only are funds due to expire for the Collider, but hundreds of major natural and physical science programs worldwide are falling victim to the global recession.)

Bolen attempts to perform the role of scientist, archaeologist and artist all at once, managing to capture fragile samples of earth and water onto a photograph, but leaving both mediums intact. He illustrates a brief, natural history of the site from the air, on the ground and in the water, and molds the mundane process of data collection into an exercise of color and texture. His exposures of soil and flora surrounding CERN are compositionally sound and the inclusion of actual images of the steel walls of the Collider is evidence of strong site-specific investigation. Yet, it plays second fiddle to the physical effects of and within Lake Geneva. For the “In Lake Geneva” series, Bolen submersed his film strips in the liquid, which carries an inherent electromagnetic charge, and the film picked up the aquatic ballet of ions, protons, electrons and quarks. The result of several dives produced stunning blobs of cerulean, flesh tones and lime green laid onto archival paper: essentially, aquagraphs.

The harmony within Bolen’s work lies in the range of elements used to mark and populate the surfaces. Nature plays the largest role, with the artist acting as intermediary. A shift from physics to metaphysics occurs when seemingly invisible, microscopic processes are revealed on a tangible plane: Bolen is not a trained physical scientist, nor does he make any groundbreaking hypotheses, but he explores a hidden world within a world by simultaneously recording and addressing a physical surface. He documents the dynamics of atomically active, open and submerged environments, elegantly displaying the results to his viewers, who may remember that the infinite atomic collisions recorded at CERN are happening every second, in every space around them.

0 Comments