“Rainbow Girls” at Cheim & Read continues Ghada Amer’s inventive strategy of using thread as paint, and needle as paintbrush, but with a marked difference. Bold embroidered stenciled text covers her canvas. Women’s rights and Amer’s stance are as forthright as her effective use of language, which becomes a physical entity with weight and force.

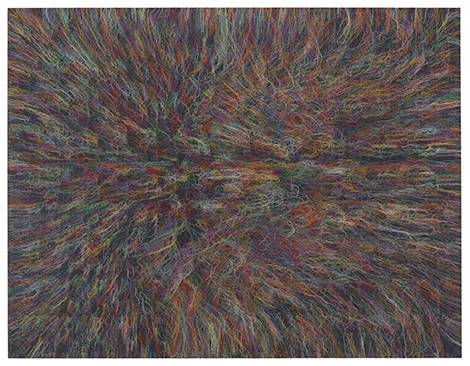

Since her mid-career solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 2008, Amer’s highly personal exploration of femininity and meditation on the private nature of ecstasy have been at the forefront of her work. Shrouded through her signature use of colorful thread that both outlines her explicit images of women and shields them from immediate visibility, The Big Black Bang (2012), like many of her works, is inspired by The Encyclopedia of Pleasure, written by a 13th-century Muslim poet who openly discussed female sexual bonding. Set against a stark black background, rushes of windblown rainbows, like nature gone awry, reveal women seeking pleasure beneath the outward aura of indeterminacy. The complexity below the loosely threaded surface, and the play between visibility and invisibility gets taken to a different plane in these text-based works.

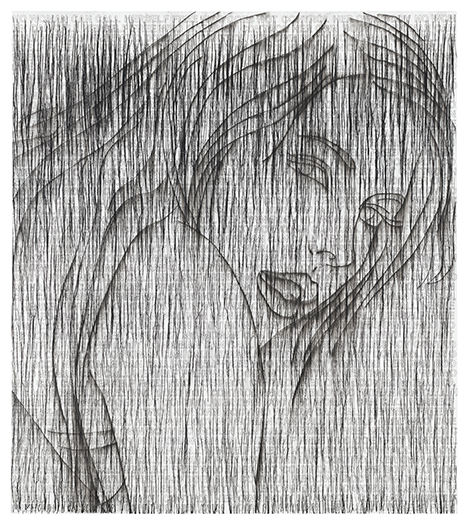

The quote “No woman can call herself free who does not control her own body,” adorns the background of Norah (2014). In the foreground a black, sultry embroidered silhouette stares out of the canvas. Resembling a smudged charcoal comic strip figure, Norah’s form is backlit by the recurring line from the birth control activist Margaret Sanger of the 1920s. Stripped from its original context, Sanger’s words still convey the collective voice of subjectivity while registering the denial and relentless silencing of that same voice.

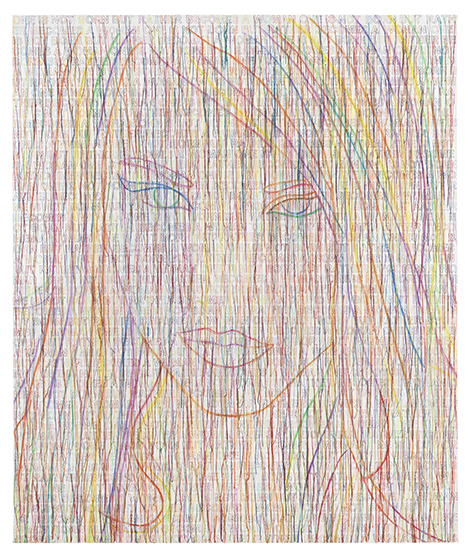

Aphorisms such as “One is not born but becomes a woman,” taken from the French feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir, shower Rainbow Girl (2013). Reminiscent of trailblazers like Jenny Holzer and Tracy Emin, whose art-texts were more personal and not always about women’s issues, Amer’s concerns follow in the vein of the African-American artist Glen Ligon. By commingling her embroidered female shadows with barely legible, repeated text, Amer highlights the plight of marginalized women, both from her own Middle Eastern background and a global context. Here, what verges on illegibility results in a series of dialogues between visibility and erasure.

Amer’s embroidered declarations refrain from being didactic, yet echo the horror of women perceived as sexual objects. The power of the stenciled text is particularly potent, especially from the context of Middle Eastern calligraphy used by artists such as the photographer Lalla Essaydi in her work. In Mandy (2013), the stenciled text “I see my body as an instrument rather than an ornament” transforms the personal and diaristic into the political and public. In Amer’s works the formal appearance of the stencil has a supercharged affect.

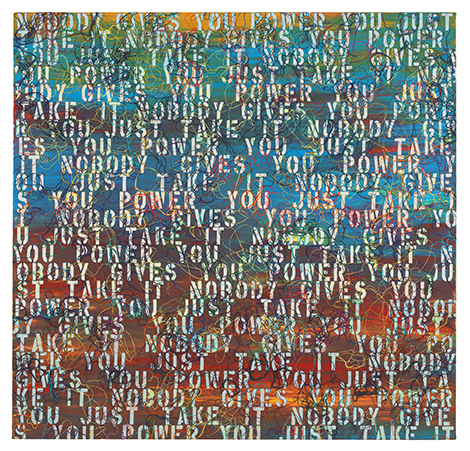

In the end, Amer’s pluralism not only addresses women’s sexuality through figuration, text-based works and sculpture, her art also embraces the comedian Roseanne Barr’s truism, highlighted in Sunset with Words (2013)—“Nobody gives you power you just take it.”

0 Comments