The world of contemporary popular culture has largely left the biosphere behind, for a world of limitless extraterrestrial space. It is not so different from the contemporary avant-garde, which remains a cerebral, intramural phenomenon. It takes an extraordinary, even cataclysmic, event to turn the conversation, the way we see and talk about art—sometimes even a change of civilization.

The 2016 edition of Houston’s FotoFest Biennial, “Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet,” made such turns of perception and conversation central to its curatorial mission, both spotlighting work made outside studios “in close contact with nature,” and sharing “the thoughts of the artists.”

Edward Burtynsky, Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Reservation/Suburbs, Arizona, USA, 2011, photo(s) © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

“Nature is not benign… ,” says co-curator (and FotoFest co-founder) Wendy Watriss. “But it’s sublime—seeing it, being a part of its dynamic; sensing awe at its diversity.” Watriss was fully aware she and Executive Director Steven Evans were going out on a tenuous limb in developing the biennial’s 2016 theme. “The word is completely out of fashion.” But she adds—“Maybe audiences need to be reminded of how beautiful the planet actually is, because sometimes that sense of beauty creates a sense of concern, and wanting to see the earth on its own terms.”

“We’re in the storytelling business,” former photojournalist and FotoFest co-founder, Frederick Baldwin states plainly, “and… we’re trying to slip this feeling about nature into the viewer’s consciousness in every way we can think of… Delivering bad news in the most beautiful way possible is not a bad concept strategically.”

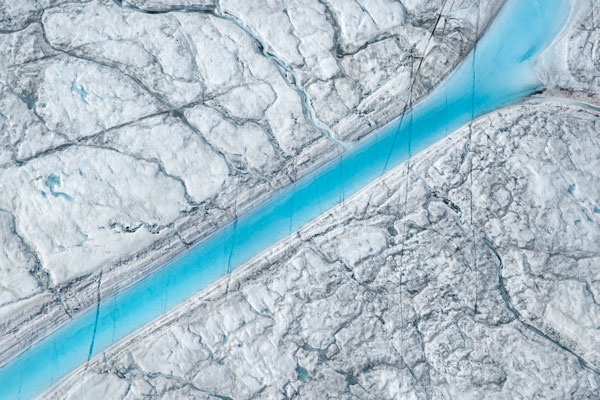

Daniel Beltrá, Water collects in seasonal lake atop the Greenland ice sheet, 75 miles southeast of Ilulissat. With the Earth’s warming climate, the melt season now stretches 70 days longer than it did in the early 1970s, 2014, From the series Greenland, Courtesy of the Artist and Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago

The story the biennial tells is cumulatively terrifying; but even the “bad news” has a startling beauty. The correspondences from one artist or one section of the biennial to the next have both poetic and evidentiary resonance—between Daniel Beltrà’s studies of Greenland’s melting icesheets and Edward Burtynsky’s human-scarrified landscapes and excavations; Jamey Stillings’ stark solar installations to Gina Glover’s “Metabolic Landscapes;” between Mandy Barker’s constellations of human detritus and Chris Jordan’s pathology of avian ingested plastic; from Karen Glaser’s “Springs and Swamps” to Susan Derges’ tide pool and shoreline studies.

Watriss and Baldwin share a background in photo-journalism; and it informs their curatorial approach. Says Watriss, “Carefully selected editorial and documentary work can strengthen conceptual work; and in fact a lot of photographic work in this subject is testimonial. I’ve come to believe that testimony is extremely important—because it’s going to go pretty soon in one way or another and other generations won’t be able to see it.”

0 Comments