Forrest Bess (1911–77) was, by his own account, a man divided. He saw himself as containing two selves: the masculine, roughneck hard-drinking fisherman, and the sensitive painter. He believed that he could unify these parts of himself by surgically becoming a hermaphrodite. Eventually, he took the drastic measure of performing surgery on himself by cutting a hole into his urethra below the scrotum. He believed that this procedure—inspired by aboriginal shamans—could unite his conscious and unconscious mind, and even grant everlasting immortality. He ultimately found the results disappointing and, ironically if somewhat predictably, fell into ill health.

A recent show at Berkeley Art Museum of his abstract paintings also included several vitrines of photographs, letters, and materials documenting his theories of hermaphroditism. The documents also include correspondence with the now discredited (but at the time leading) sexologist, John Money, who infamously performed gender reassignment surgeries on infants born with ambiguous genitals—often with what turned out to be tragic results.

Money, for his part, recognized that Bess’ ideas were crackpot. Despite this fact, Bess’ embrace of indeterminate gender identities was ahead of his time. A photo of Bess’ scarred genitals might seem exploitive—a distraction from his work that turns Bess into “that painter who cut a hole in his perineum”—until we learn that Bess had tried to convince Betty Parsons, his avant-garde New York gallerist, to show these documents along with the paintings. Unfortunately, she denied him this opportunity. It is easy to see why, but it is hard to deny their relevance to his oeuvre. Had they been shown then, Bess’ work might have served as an inspiration for several generations of artists who later explored issues related to body modification, gender identity, and esoteric personal cosmologies.

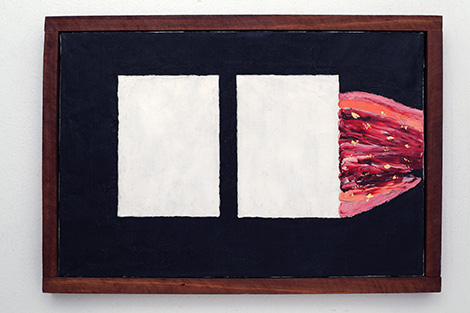

These ideas about hermaphroditism and mythology also inform in his paintings. A recurring codpiece-like form—Arp-esque in its abstraction—is repeated and serves to emphasize his genital preoccupations. One painting, Untitled 12A (1957), epitomizes this tension between the abstract and the corporeal. It features two white rectangles on a black field. Yet one of these rectangles trails a fleshy, painterly smear of pink, salmon, red and crimson like a wound flecked with gold paint. The squares, taken by themselves, recall Malevich but, for Bess, there’s no “non-objective” abstraction; the canvas immediately becomes a surrogate for the body—here a metaphor for his desire to attain an ideal form in one bloody surgical stroke.

Bess described himself as a “Visionary Painter.” He claimed to see visions in the state between waking and sleeping, made sketches of them in the morning, and then translated them into paint at night. Paradoxically, these ephemeral visions are presented in assertive, raw, and precisely articulated surfaces: an emphasis on their physicality. This is expressed through his mastery of gluey, gunky, awkward painterly effects; infinitesimally varied palette knife smears, controlling the things that paint does more commonly when it is not quite being controlled. The defining characteristic of his work is a fierce urgency born from the internal necessity to render his visions in paint.

It is, then, a bit strange to find that some of his best paintings are those that are more firmly grounded in the world, often alluding to landscapes, and reverential of art history. His less interesting works are those that seem to venture too earnestly into surrealism, hokey primordialism, or symbolist cheese. These motifs are often either too ponderously “archetypal” or too abstrusely coded and personal. One painting titled Thunderbird (1965) depicts a black iconographic bird ascending in a cloud of smoke below a yin-yang moon. This painting is redolent of ’60s era “vision quest” imagery à la Carlos Castenada in a way that feels dated now. The best painting might be Dedication to Van Gogh (1946). Van Gogh’s bucolic effervescent fields are transformed into a portentous sunbaked Martian hell-scape, flattened and abstract. It’s not quite the French countryside—more like Munch’s screaming fields. But even more so: Bess’ zigzags make Munch’s swirling background seem calm by comparison. The slight white spaces between the marks, activated as negative space, recall Cézanne but have their own jagged electricity. A strange paradox: his work imbues paint with a kind of psychological intensity precisely when he seems to be the least overtly concerned with psychology. It is a good reminder that not all of our talents require theories and that we might, sometimes, do better without over-thinking things.

0 Comments