In Ellen Cantor’s restaging of Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art by Women, the landmark show that she originally curated in 1993 at the David Zwirner Gallery, there are the obvious standouts: Yoko Ono’s Object in Three Parts—Revolution (1966), recreated in 2016 with ‘new parts’ but the same formula of objects (the diaphragm, condom and birth control pill); Louise Bourgeois’ Janus and Janus in Leather Jacket (both 1968); Nancy Spero’s Sheela and Dancing Figures (1986); Zoe Leonard’s photographs, Frontal View and View from Below, Geoffrey Benne Fashion Show (1990); and other well-known artists protesting male-dominated worlds.

But why return to this today? To protest power and the controls over the female body is contentious however done. That this is still at issue is the reason for the show both then and now. Several of the works are sexually explicit and directly confront a culture that still attempts to control women’s sexuality. In SELF (1970–76), Lynda Benglis’ iconic photograph of her naked and sexually charged female body wearing cool dark sunglasses, Benglis holds a lengthy latex penis that projects from her groin. A centerfold ad in Artforum (1974) made it infamous. Projections of maleness on the female body in order to alter inscribed subconscious notions of male desire and control voiced in the 1970s are still valid. It is these forms tied to representations of gender and its authoritarian hold over the body and pleasure that make the return of this exhibition desirable. Feminist theorists like Spivak and Butler have said that gender is a process of the body to form an identity over time, in its sexuality and authority. It is a reaction and a confrontation at the same time.

Zoe Leonard, Frontal View Geoffrey Benne Fashion Show, 1990; ©Zoe Leonard, courtesy of Maccarone Gallery, New York.

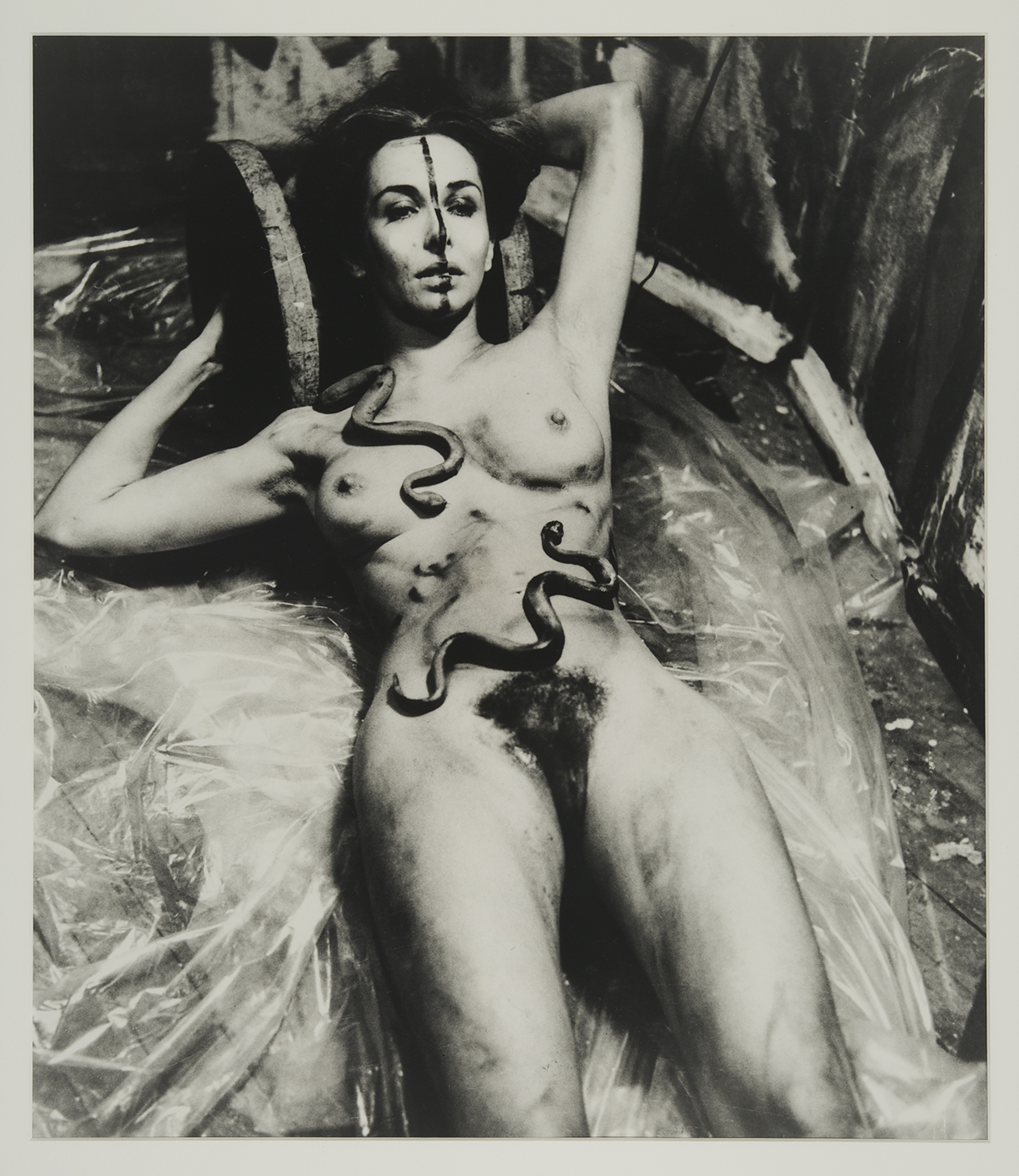

How does the female body reclaim itself? Benglis takes a performative approach, direct and explicit: Female Sensibility (1974) and Learning the Ropes (1992) play on a small circa 1990s TV, in a loop of eight different short films. These include scenes from Kate Dymond’s Nice Girls Don’t Do It (1991) and filmmaker Maria Beatty’s Imagine Her Erotics—Carolee Schneemann (1993). Sadly missing are the Yoko Ono and the sexually explicit Annie Spinkle performances that were in the original show.

In 1993, “Coming to Power” minimally addressed gender queering or sexuality that fell outside of the male/female binaries. These are only marginally represented today. In Tattoo Girls #3 (1988) and Skateboard Girls (1990), GB Jones depicts boyish women that disturb traditional ideas of female sexuality and the body. Untitled (Pentagon) (1992), one of Monica Majoli’s paintings of pornographic scenes, shows two women together. It is such images paired with the X-rated that engage this ongoing discussion of who controls sexuality and representations of gendered identity.

These 50-some works refute the marginalization and containment of women as subjects of the male gaze, reiterating the importance of remembering this history, needed just as urgently now as it was 23 years ago.

0 Comments