Contrary to certain art historical narratives, painting has never waned, but only been ever more rigorously interrogated—usually by the artists engaged with the medium. Chris Barnard is one of those artists mining and turning over the modernist tropes of figural representation, abstraction, message and picture-making, as if to question the very forces driving them.

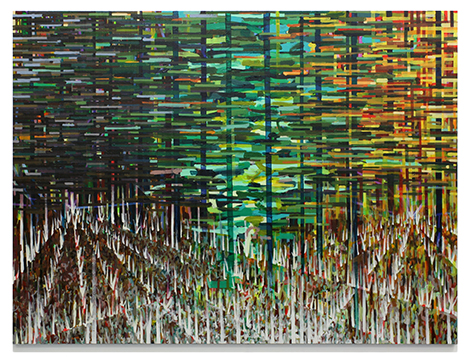

The title of his show, “White Tide,” induces a bit of foreboding, somewhat offset by the shimmer of the first two paintings the viewer is immediately drawn to upon entering the gallery. Bad Seed (all works 2015) references both the representational conventions of landscape painting and that most implacable of modernist tropes, the grid. Dark blue and green verticals appear thickly stenciled onto the canvas. The horizontals modulate in staccato dashes left to right from cool blues and purples to greens and finally to warmer luminescent amber, red and chartreuse tones on the right. But the lower portion of the canvas dissolves our perception of this rational left-right progression, with short white verticals, like white flames or filaments receding in crisscrossing diagonals toward white-light vanishing points on either side of the canvas.

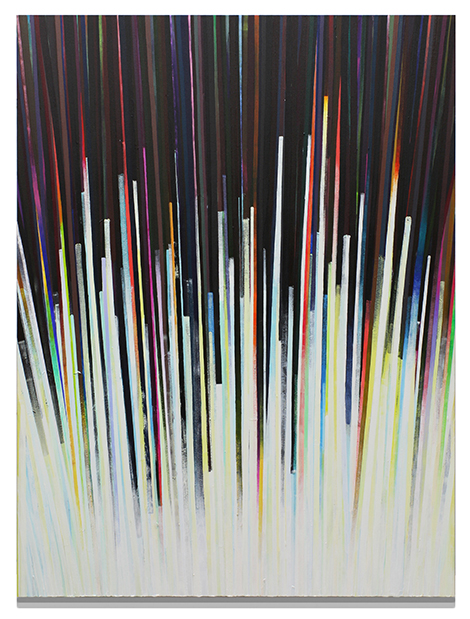

White Hole might obliquely address what lies at the end of those spiky avenues. Here muddled blue-violet verticals descend ambiguously into the white “hole” of the lower part of the canvas. There are echoes of Morris Louis (as there are of other classic abstractionists in other pieces), but there’s nothing soft or veiled here. Barnard knows how to be simultaneously stark and sensual.

With a title like Deepwater Horizon, Barnard is explicitly touching on shock-doctrine political, cultural and environmental issues; and sure enough there are references to oil slicks, murky depths and churning, fulminating debris (in the most gorgeously tactile whites, veined with cobalt flecks, pinkish streaks, eliding into watery blues—Barnard is a master of the corrupt, not-quite-white). In certain respects, this is almost literally rendered imagery. But Barnard is also mining the forbidden terrain of the beauty we find in the pathology, the mythic fail measured by exquisite inflammations, volatile reactions and recombinations.

An ocean of acid yellow fills the upper half of White Tide sliced by undulant wave strokes in white that tumble into a glorious, thickly impastoed cascade of white in the lower portion of the canvas. Barnard risks a kind of brutalism in these works, which today might pass for environmental realism.

In all the chromatic sensuality of this work, we are effectively served an indictment. But there is also dialogue between the rationality driving us to the brink and values that nurture a sustainable civilization. Hope may be elusive, but Barnard’s work suggests we will go on grasping at beauty even as we gasp for our last breath.

0 Comments