Lately, I’ve noticed mysterious islands along California freeways. The half circumferences of curving transition ramps from one freeway to the next form their perimeters. Many contain terraces of plants native to this arid region, large rock formations, and gravel pathways.

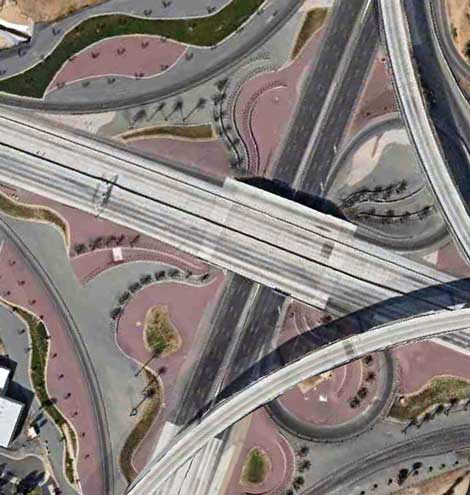

The islands are part of a new freeway beautification strategy built by the state of California’s freeway management department, Caltrans. Aesthetics are important to Caltrans, actually. In a 2010 Press Enterprise newspaper article, Caltrans District 8 Director Ray Wolfe said, “Drivers get an impression of a community from what they see along the road.” The islands would suggest an odd kind of civic aestheticization seen from afar only since there is no apparent everyday access for the average person. However, there has been a shift in the flora. Maintenance requirements have increased as more freeways are built and others are expanded, such as with the interchanges for the 215, 91, 60 freeways. Wolfe says that the new strategy is to have more native species that require less water and caretaking. Regarding planting less palm trees and lush grasses, he so aptly states, “in a wind-whipped desert area like most of the Inland [Empire] area, it just is not ‘what we are.

‘”

Satellite images of concrete islands at the interchanges between the 91, 215, and 60 freeways, Riverside, California. Photograph by Tyler Stallings via iPhone capture from Google Earth

But despite being aware of Caltrans’ aesthetic motivations, the islands remain strange. They appear ready for habitation because of being constructed and manicured to a point that suggests an urban, pocket park. However, there are never any people strolling, taking relief from the difficult culture bound with concrete thoroughfares.

So, perhaps the governor is preparing formerly marginal land for habitation by a sinking middle class? Or maybe they will be sites for more prisons with prisoners kept in check by all seeing motorists? They would first have a low-flying, bird’s-eye view as they drive above them on freeways supported by high columns, then keep a watchful eye as they transition downward around the curve of the ramp.

Now, J. G. Ballard’s 1974 novel, Concrete Island, comes to mind. It is a variation on Daniel Defoe’s 1719 Robinson Crusoe story in which the protagonist crashes his car and finds himself stranded in one of these islands near an English motorway spur. Past victims, now Island occupants, who wish to remain unnoticed in their newfound paradise on which they have squatted, thwart his escape attempts. They fear that he will expose their stranded, car wrecked life that they have embraced.

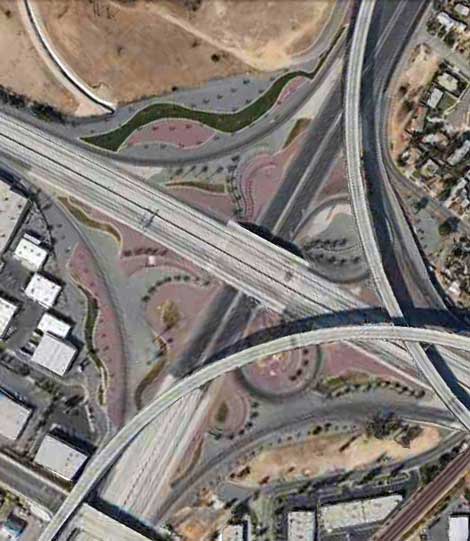

But, instead of considering such islands from an accident’s accidental vantage point or from a near-future dystopian view, how about one that considers repurposing them actively? It is how someone in my ongoing thought-experiment on a speculative, secessionist desert-based community that I call Aridtopia would reframe this received landscape that is situated in an arid region. This attitude of repurposing finds kinship with another SoCal artist-urban planning project. As stated on the project’s website, Islands of L.A. “was conceived of as a project to investigate the use and availability of the marginalized yet highly visible public spaces of traffic islands.” In other words, it focuses on concrete islands accessible by pedestrians rather than those viewed only through the cinematic-like “screens” of windshields.

Satellite images of concrete islands off the 14-Freeway, Avenue L exit, Lancaster, California. Photograph by Tyler Stallings via iPhone capture from Google Earth

The Caltrans beautification strategy could be reconsidered as less about pleasing the eyes of a speeding motorist and more about providing a purpose-built, high-concept setting for the motorist to contemplate about what kind of society they would initiate if given a blank slate of an island.

How would they start their own country? Would they veer towards the utopian, as in the late-1960s television series Gilligan’s Island, in which bamboo and palm fronds are the base materials for an infinite amount of contraptions for convenience; or toward the dystopian, letting the primitive, territorial, animal consciousness rise to the surface as in William Golding’s 1954 novel Lord of the Flies?

I would suggest that people rally and occupy the islands. Instead of the Occupy Movement from 2011, it would be the Concrete Island Crusade of 2013. Instead of squatting in front of seats of power, whether government or corporations, these new inhabitants will simply just start their new way of life. Crops will sprout and huts will be thatched.

These concrete islets could form a chain of keys found along the interlocking web of California freeways. Collectively, they could be declared as forming a new, unified country—perhaps, it will become Aridtopia—like Indonesia’s archipelago of 17,500 islands, although bound by desert rather than ocean. Freeway shoulders could be designated as Aridtopian rightaways to the concrete islands.

Perhaps, these new urban, island inhabitants will even take control of the freeway transition points. They will be gatekeepers, literally, charging a fee to transition, whether to the next freeway or into a new consciousness. Freeways to Freedom!

This essay will be included in a book of forthcoming, collected essays by Tyler Stallings, titled Aridtopia: Essays on Art & Culture from the Deserts of the Southwest United States (Blue West Books), http://www.bluewestbooks.com. Tyler Stallings is a curator and writer who lives and works in Southern California, http://tylerstallings.com.

0 Comments