Rallying against overwhelmingly white, male perspectives in art history, “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85” at the California African American Museum (CAAM) is not to be missed. The exhibition highlights the stylistically varied work of over 30 artists and re-centers the focus to a group that has historically been marginalized and left out of both the mainstream and feminist dialogues during those decades. Groups such as the Harlem Renaissance, Spiral, and the Black Arts Movement are represented, and given the commentary provided by CAAM, the exhibition provides newly illuminating historical context and background for these diverse movements and the artists represented.

Betye Saar (American, born 1926). Liberation of Aunt Jemima:

Cocktail, 1973. Mixed-media assemblage, 12 x 18 in. (30.5 x

45.7 cm). Private collection. © Betye Saar, courtesy the artist

and Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California. (Photo: Jonathan

Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)

Many of the artworks are distinctly political, conveying the urgency of calls-to-action—the work of Betye Saar in particular has this effect. Saar’s pieces contrast racist images of people of color with iconography of the Black Power movement to create striking symbolism. The Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail (1973) features a bottle with a “mammy” figure on the front that has been turned into a Molotov cocktail. Her film, Colored Spade (1971) uses similar pairings, meshing derogatory images with depictions of black power.

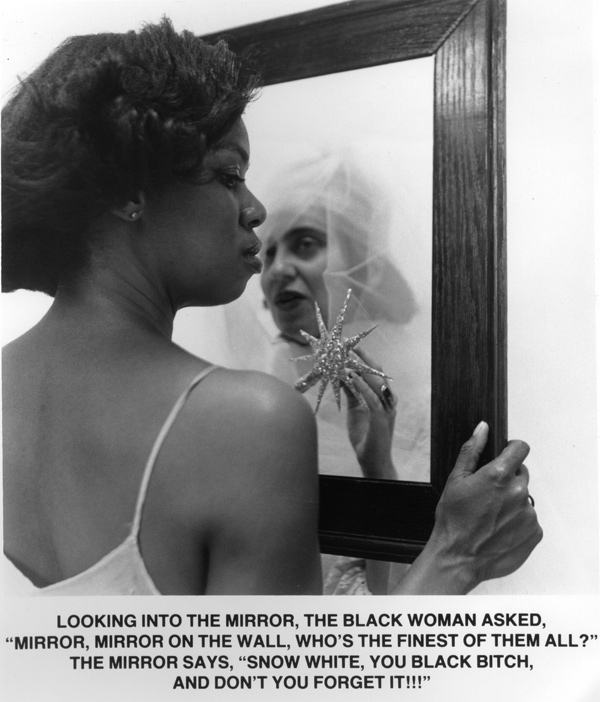

Carrie Mae Weems (American, born 1953). Mirror Mirror, 1987–

88. Silver print, 24 ¾ x 20 ¾ in. (62.9 x 52.7 cm). Courtesy of

the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Carrie Mae

Weems

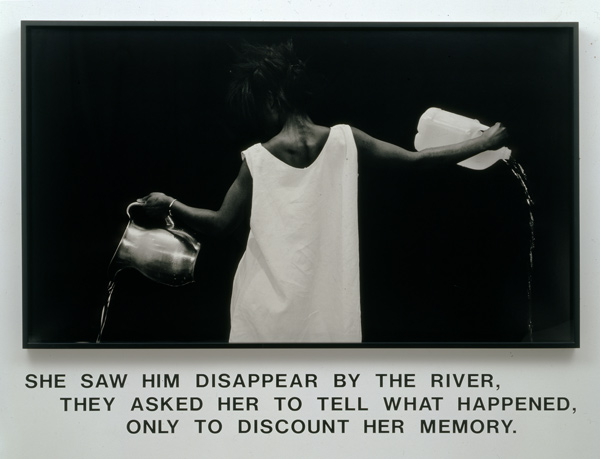

Photographers Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems combine photos with words to create sardonically witty and moving images. Simpson’s Waterbearer (1986) depicts a young black male pouring out two jugs of water, with the words “SHE SAW HIM DISAPPEAR BY THE RIVER, THEY ASKED HER TO TELL WHAT HAPPENED, ONLY TO DISCOUNT HER MEMORY”. The piece is regrettably reminiscent of photos and reports of the murders and disappearances of young black males today, in which testimonies and footage often still lead to a not guilty verdict.

Faith Ringgold (American, b. 1930). Early Works #25: Self-

Portrait, 1965. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.6 cm).

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Elizabeth A. Sackler, 2013.96. ©

1965 Faith Ringgold. (Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn

Museum)

The works are not all overtly political, however, with artists like Virginia Jaramillo whose abstract expressionist paintings are on display. Other artists like Emma Amos and Faith Ringgold paint self portraits in their respective styles that do not appear particularly radical, until one realizes that to be a black woman artist, and to paint one as well, is in and of itself a radical act.

The show at CAAM refuses to be put into a tidy box. The works are sprawling, multi-disciplinary, and diverse, and most importantly demonstrate how the fixed state of art history is disputable.

“We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965 – 85,” October 13, 2017 – January 14, 2018 at California African American Museum, 600 State Drive, Exposition Park, Los Angeles, CA 90037, caamuseum.org

0 Comments