Almost since its inception, photography has been characterized by historians and critics as perpetually in crisis. The current divergent trends—a democratizing of the form through digital cameras and social media vs. the ontological investigation of the medium by focusing on chemical processes, painting with light and digital construction of images or the overlap of photo and other media—seem congruent with the hybridization of other media in contemporary art. It is only the ghettoizing of photography as a discipline separate from other art practices that raises its wide-ranging explorations to the level of “crisis.” One could easily say that contemporary art in general is perpetually in crisis, yet we do not find the ongoing cycle of creation, destruction and reinvention in the broader contemporary art context characterized as “crisis.”

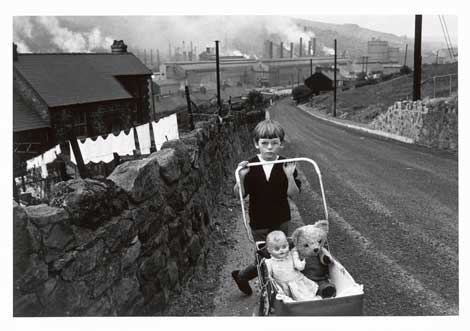

Bruce Davidson, Wales, 1965,Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Henry S. Hacker, © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Amidst these debates a new show at the Huntington Library, produced in collaboration with the Yale Center for British Art, explores the work of two American photographers who practiced as the modernist narrative in photography ended its dominance. The show’s title, “Bruce Davidson/Paul Caponigro: Two American Photographers in Britain and Ireland,” is modest regarding the heft of the two photographers and their relative positions as important exponents of two major streams of modernist photographic practice.

An astute observer of people, Davidson freelanced for Life magazine, and in 1958 at the age of 25 became the youngest member of the prestigious Magnum agency founded by Henri Cartier-Bresson. In 1960, on his first trip to Britain, shooting with a 35-millimeter Leica, Davidson caught subjects unaware or noticing the camera at the snap of the shot—a dramatic contrast to the awareness that permeates our contemporary life: we constantly perform for the camera and at a young age, learn to carefully mediate our social identities.

In 1965, Davidson traveled to Wales, dropping his Leica in favor of a 4×5. The carefully orchestrated portraits of Welsh miners and their families reflect the reality that photography is not objective, nor was it ever a mere recording of facts.

Caponigro, who briefly encountered Ansel Adams and other Bay Area photographers, found a mentor in Minor White. Early on he learned Adams’ zone system and focused on landscape photography. In 1966 he traveled to Ireland on a Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph Celtic art and architecture. The following year he photographed Stonehenge, and in 1968 had a solo show at MoMA of the work from his Guggenheim year. The search for sublimity found in Caponigro’s decades-long exploration of Celtic sites and the landscapes of Ireland and Britain serves as a counterpoint to the ontological explorations of a new generation of process photographers examining the structural limits of photography.Modern photography, of course, has long insisted that the lens is not neutral. Whether seeing through a lens or with the naked eye, observers make all manner of conscious—and unconscious—edits through the acts of seeing and remembering what has been seen. Caponigro and Davidson demonstrate how the camera becomes a tool to shape perception toward a specific vision (or interpretation) of the world. Isn’t that what we expect artists to do, regardless of medium?

“Bruce Davidson/Paul Caponigro:

Two American Photographers in Britain and Ireland”

Through March 9, 2015

The Huntington Museum/MaryLou and George Boone Gallery

www.huntington.org

0 Comments