The 60th anniversary tour of the Paul Taylor Dance Company has provided an occasion for the revisitation or revival of a number of classic Taylor dances. I was just tempted to call them ballets; and the first of those programmed for Friday evenings performances, tread a sometimes ambiguous terrain between the two classifications, but did so steadily and without ambivalence. (I always think this is key to the Taylor style – key to its clarity and its occasional humor.) Taylor’s use of classical or baroque music was once thought to be slightly ‘cheeky,’ teasing (if not hazing) the classical ballet or other serious modern dance idioms. This was only the second time I’d seen the Airs (not arias specifically, but set to overtures and ensemble music for three Handel operas, as well as four concerti grossi). But there wasn’t a single moment where the music felt inappropriate.

The dance sequence – more or less evenly split between ensemble dances and dances featuring two principal dancers or a soloist – was and remains an updated, minimalist rendition of a masque, or perhaps more precisely, a fête galante, updated along the lines of L’année dernière à Marienbad. If that sounds like a stretch, consider the development of the dance suite from the initial stage configuration in the Overture and Largo and through the G-major Concerto solo (by Laura Halzack): the semi-recumbent female dancer isolated just off center-stage with the three male dancers arrayed on the left as if in a colonnade (an abstraction of the most basic Arcadian motive, with an emphasis on the dancers’ isolation); the transition of the other female dancers from off-stage through ‘the colonnade’ with intersecting triangulations upstage and down, as the dancers pair-off in succession, alternately circling and paralleling each other, processing and recessing as the dancers take their solos – a kind of sarabande step broken and reversed as the dancers regroup; and finally the courante-gavotte with Taylor’s trademark forward springs, broken bourrée and jackknife jumps. The court flirts (and certainly gavottes), but the sparks fade as fast as they fly. Ms. Halzack’s final solo (after a vigorous company bourrée) amounts to an extended reverence to the fleeting fête. There’s nothing irreverent about it – and it was danced superbly.

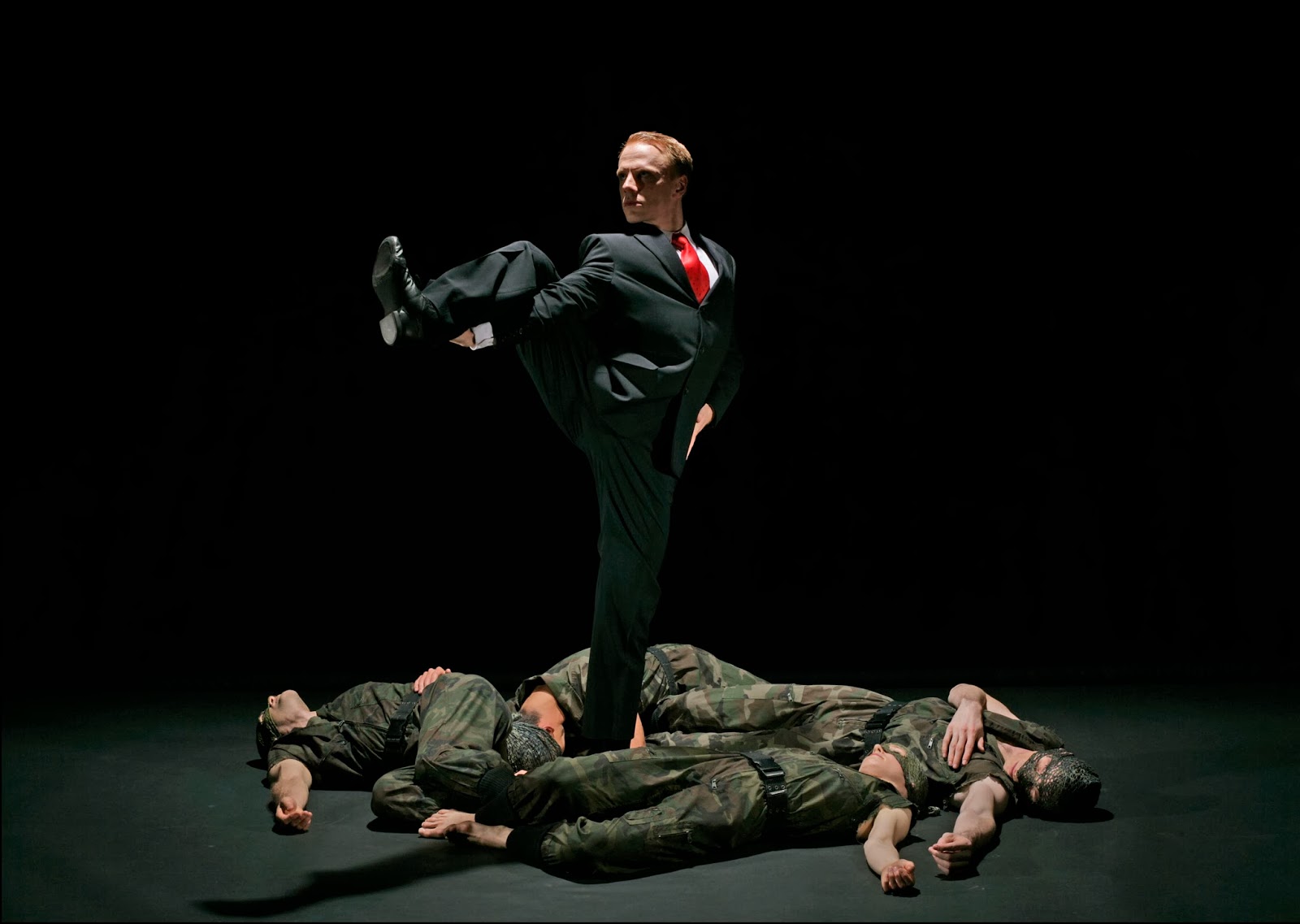

Banquet of Vultures is from 2005 – which places it about a year after the news about Iraq war prisoner and detainee abuses at Abu Ghraib broke. I don’t think it’s any small coincidence that we’ve also seen the release of Errol Morris’s The Unknown Known in recent weeks. It’s timely and appropriate to contemplate our lost Arcadia as we consider the less-than-Platonic caves in which we’ve buried our consciences. The Santo Loquasto set (lighting by Jennifer Tipton) places most of the company in a sewer-tunnel murk, moving as in a swarm, and brandishing flickering candles (which may double as weaponry). The costumes are uniform streamlined olive-drab camo fatigues (with two stand-out exceptions). As in any ‘war’ situation, hunters are also hunted; the sentries can become prisoners; and the prisoners a single organism, as soldiers are mere appendages of a larger apparatus. Dancers pair off, turn, are tugged at or ‘struck,’ and fall; isolated singly or in groups under follow-spot or pin-point cones of light, propping each other up in turn. Through this twilight world struts a fellow in a suit and red tie (and shoes), his movement angular and aggressive, lashing, jabbing, pouncing, and otherwise dominating the space. I suppose that might translate to a certain style of U.S. diplomacy (a sly reference to Paul Bremer?); though looking back at that time, it seems emblematic of a much larger crime. The dancing suit convulses and collapses before making its Frankenstein exit – which also seems a prescient metaphor.

Gossamer Gallants, a choreographic battle of ‘blue-fly’ beaux and ‘lace-wing’ belles, was a trifle – a pantomime as much as a dance – and not to be taken seriously. But even here, you couldn’t help feeling a perilous undercurrent (as insect populations are imperiled alongside a thousand other species). Beaux and belles have all fallen in the approaching failure of a government that was once the Enlightenment’s greatest political legacy; and as drone diplomacy seems in step with an encroaching drone democracy, the songes agréables of the last Handel dance seemed poignantly elegiac.

0 Comments